Restless Eye

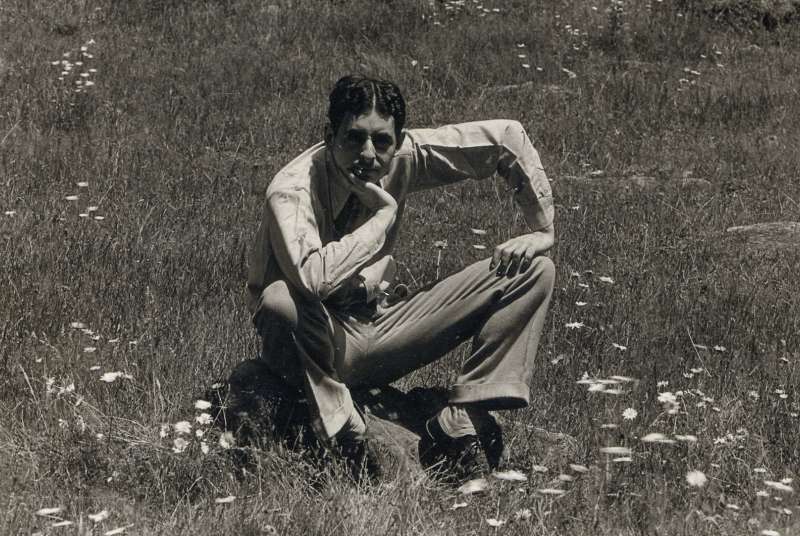

“Be intensely yourself” was Ralph Steiner’s advice to aspiring photographers. In a career that spanned seven decades, the artistic acrobat leapt from one genre to another. He produced stunning images notable for their odd angles, abstraction, and bizarre content.

Steiner was pen pals with Ansel Adams. He dined with photo pioneer Alfred Stieglitz and his wife, artist Georgia O’Keeffe. He rubbed shoulders with Henri Cartier-Bresson and was a lifelong friend of Dust Bowl documentarian Walker Evans.

“He was one of a few people who bridged pure abstraction and representation in photography and folded a social, political bent into his work in the 1930s,” says Kelly Sidley ’98, an assistant photography curator at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Steiner’s bold eye won him multiple spots in the first photography exhibition at MoMA in 1937, a groundbreaking event that came at a time when photographers sought validation that their genre was a legitimate art form.

Nearly 60 years after graduating from Dartmouth, Steiner wrote that he “became a madman photographer to escape going into the [family] brewing business.” It was not an easy transition. “In those days—1917 to 1921—to be at Dartmouth, Jewish, neurotic, and shy was like being a Martian with a green head and four eyes,” he told an interviewer. “I was a skinny little guy, afraid of the world, and couldn’t very well be captain of the football team, so I took up photography. There must be something about shyness and the darkroom, something in all that hiding in the gloom.”

Steiner, a chemistry major, wanted to study photography at Dartmouth, despite fearing students might think he had “homosexual leanings” due to his serious interest in the arts. Biology professor Leland “Doc” Griggs, a nature photographer, told Steiner he could convince the College to let him teach a photography course. Steiner was thrilled.

He was the only student in the class. The two eccentrics (Griggs enjoyed walking around town with a tame crow on his shoulder, according to Steiner) got along splendidly. Griggs’ kitchen served as their classroom, and “gigantic” portions of strawberry shortcake highlighted their meetings.

Steiner was known for saying, “By showing a picture, you’re showing an X-ray of your heart.”

Upon graduating, Steiner published his first book, Dartmouth. Its 24 images show the campus in winter stillness and at play. “It is not the moment of majesty that [Steiner] prefers to catch, or of climax—but the moment of revelation,” Dartmouth art professor Homer Eaton Keyes, class of 1900, wrote in the book’s introduction.

Steiner evolved his soft-focus Pictorialism style to become a sharp-edged Modernist. His 1920s photos of typewriter keys and industrial power switches are “geometrically bold, stark, graphic images that celebrate the machine age,” says Anne Havinga, senior curator of photographs at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. His lens also captured warped movie, cigarette, and soda pop billboards that were “at once celebratory of mass culture and critical of the phony promises of the advertising industry,” according to Anne McCauley, a professor of the history of photography and modern art at Princeton.

Seeking other challenges, he left photography for the movies as the decade ended. In 1929 he directed H2O, one of the first American art movies, which consists of 11 minutes of water rippling, gushing, dripping, splashing, undulating, and reflecting light. He worked as cinematographer on the 1936 Dust Bowl documentary The Plow That Broke the Plains. Following work as photo editor for the experimental leftist newspaper PM, Steiner went to Hollywood in the early 1940s for an unsatisfying stint as an assistant producer for MGM mogul Louis B. Mayer.

As a magazine and publicity photographer after WW II, Steiner displayed his mastery of portraiture. He had an eye for the freakish and quirky. He shot stripper Gypsy Rose Lee and her sequined entourage arrayed around a Rolls Royce on, of all places, a dirt road. On assignment in the late 1940s for Walker Evans, then a Fortune magazine staffer, Steiner wangled CEOs into kooky situations, such as riding a burro or driving a forklift.

Later in life Steiner fell in love with classical forms. His images of sheets billowing on clotheslines make them look like Greek gowns. He even made a movie with the wry title A Look at Laundry.

“When you talked to him, he’d go in one direction and then another, and that would lead him instantly into another, and he wouldn’t get lost, but the listener might,” says Jim Hughes, founding editor of Camera Arts magazine. He and Steiner became friends when Steiner, in his 80s (“a bundle of energy,” Hughes recalls) lived in a white frame house near the Green in Thetford, Vermont. “His eyes, even behind thick lenses, did twinkle when he wanted to be amusing, which was most of the time,” says Hughes.

He visited Steiner at his summer place on Maine’s Monhegan Island, where the photographer spent hours patiently waiting to capture the right cloud at the right moment. He hoped the resulting images would break the shackles of consciousness and cause viewers to free associate. This dream-stuff is the subject of his 1985 book In Pursuit of Clouds, which was published a year before his death at 87.

“It’s a shame he’s not better known,” says Edwynn Houk, whose self-named galleries in Manhattan and Zurich represent the estates of top Modernist photographers (but not Steiner’s). One of Steiner’s most powerful images, says Houk, shows two tiny figures standing against the looming vast sea as seen from a high vantage point. Two Men and the Ocean is “virtually a self-portrait of the artist,” he says. “Someone who feels so isolated and separate from the world. It seems like a very personal picture.”

“I’ve never had the need to shove what I’ve done under anyone else’s eyes,” the self-effacing Steiner once said, and Sidley and Houk agree that the rarity of his gallery shows hurt his career and limited his name recognition.

Less interested in fame than in being true to himself, Steiner said, “A creative person sees things not as they are, but as he is.” He was known for saying, “By showing a picture, you’re showing an X-ray of your heart.”