“I try to communicate that everyone makes up fictions,” says Alexander Chee. “Writing them down is what the writer does.”

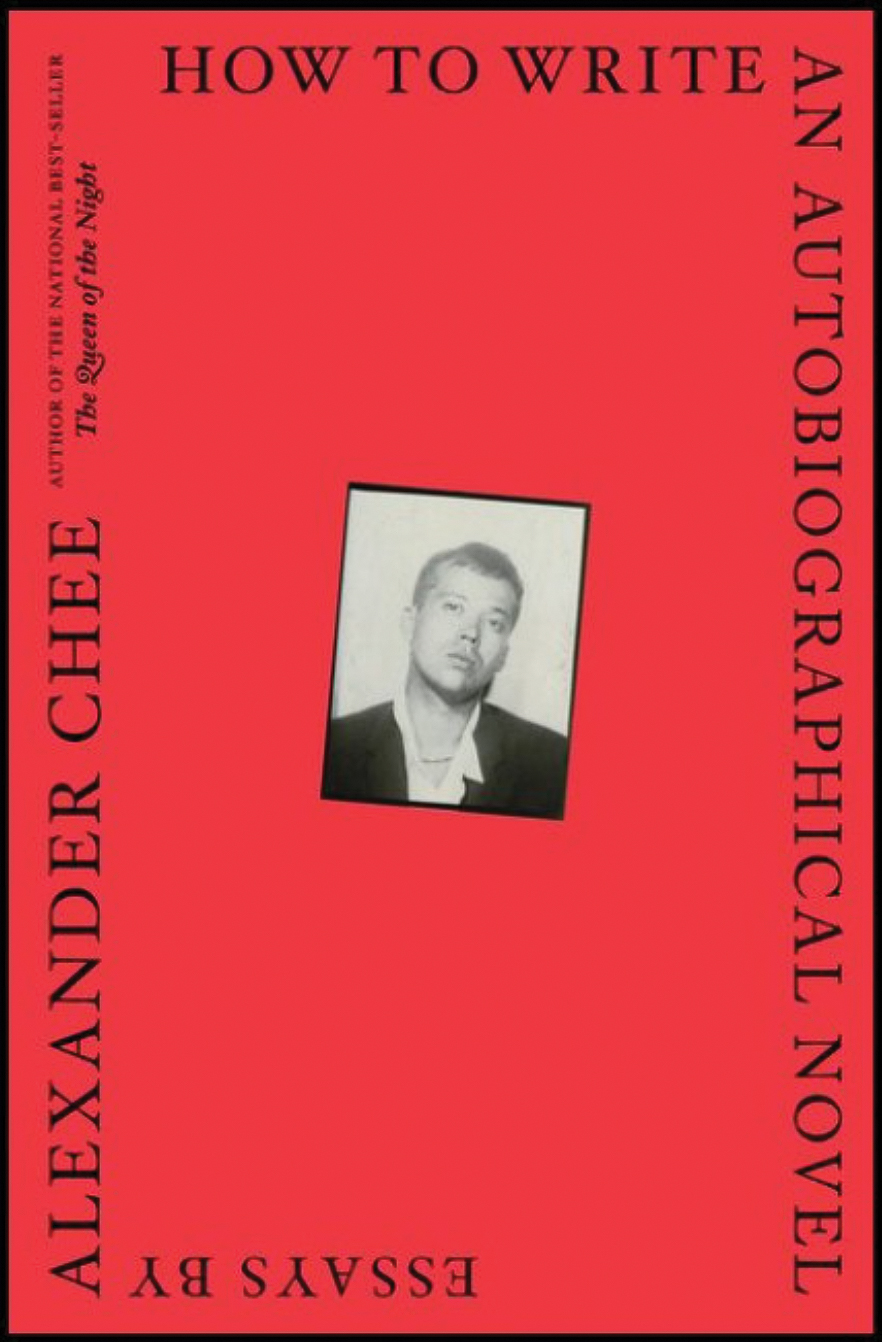

It’s no coincidence that several essays in his cunningly titled new collection, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, opine on writing or the teaching of writing, in ways both comic and profound. “Invent something that fits the shape of what you know,” he suggests in the title essay. “To do this, use the situations but not the events of your life.” [Read an excerpt here]

Chee, an associate professor of English and creative writing, did just that in his elegant and elliptical first novel, Edinburgh (2001), about the aftermath of sexual abuse. His second novel, The Queen of the Night (2016), was a major departure: a picaresque tale, populated by historical characters, whose protagonist-narrator is a shape-shifting opera diva in 19th-century France.

But teaching has long been central to the 51-year-old Chee, who came to Dartmouth two years ago. His impact on his students at his two alma maters, Wesleyan University and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, as well as at Princeton, Amherst, Dartmouth, and elsewhere, was recognized by the literary magazine One Story, which named him 2018 Mentor of the Year. The prize, previously awarded to Ann Patchett, Dani Shapiro, and other literary luminaries, was a booklet of stories about his teaching by several former students. Among the common threads, says Chee: “I took them seriously in a way that they had to adjust to—that helped them take themselves seriously.”

Chee’s teaching and writing reflect “his ongoing inventiveness, his refusal of certainties, and his apparently constant evolution,” says Dartmouth English professor Melissa F. Zeiger. Observing his classes made her want “to rethink the staging of my own courses and the way I write, to be braver and more inventive,” she adds.

“A large part of the act of teaching is simply to look students in the eye and believe that they can do it,” Chee says in late May, shortly before heading to Florence, Italy, to teach a creative writing course. “I’m trying to take off the table the anxiety about ‘Will I be good enough?’ Even fighting against that anxiety takes energy away from learning how to be good enough.”

Annie Ma ’17, a journalist in San Francisco who took Chee’s speculative fiction course “Imaginary Countries,” says Chee “really pushed me to be fearless as a writer, to not limit myself with premature self-editing, and to not worry so much about how to do things the right way. He believed in me when I was starting to doubt myself as a writer trying to break into a tough field.”

Nicholas Mancusi, a 2010 Amherst graduate, was a student in Chee’s advanced fiction course. “His manner as an instructor was kind, patient, deeply considerate, and stunningly perceptive, and the classroom environment took on these qualities,” Mancusi recalls. “But I think what I most learned from Alex is how a writer, or any artist, needs to respect themselves and their craft. It was Alex who first convinced me that I could take myself seriously as a writer.” Mancusi’s debut novel will be published next summer.

Aja Gabel, whose debut novel The Ensemble was published in May by Riverhead Books, studied with Chee about 15 years ago at Wesleyan. “He’s wise and irreverent, generous and exacting,” says Gabel. She recalls Chee pulling out the novel The Lover by Marguerite Duras and telling her to read the first paragraph aloud, saying it would teach her “about how sentences and images can do whatever you make them do, if you’re good enough.” The lesson stayed with her, and she has tried to pass it on to her students.

Chee says he draws his practical, craft-centered approach to the teaching of writing in large part from Annie Dillard, his literary nonfiction professor at Wesleyan. In “The Writing Life,” from How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, he notes that Dillard—who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1975—taught him to choose strong verbs and to regard the literary essay as “a moral exercise that involved direct engagement with the unknown.”

Despite stellar instructors and some early plaudits, Chee did not find immediate publishing success. But his long apprenticeship and colorful professional detours provided plenty of fodder for his new essay collection: Through the years Chee did stints as a Tarot card reader, a cater-waiter for the conservative commentator William F. Buckley and his wife, and an AIDS activist. In “The Querent,” he writes that Tarot plunged him into “too close contact with the lives of others”—and showed him only “the possibilities of the present, not the certainties of the future.” Being a cater-waiter similarly “allowed me access to the interiors of people’s lives,” he writes in “Mr. and Mrs. B,” which highlights the contradiction between Buckley’s public expressions of homophobia and his wife’s AIDS-related philanthropy.

Chee put aside what would have been his first novel—about AIDS activists on the West Coast—to struggle with Edinburgh, a tragic literary and mythic transmutation of his childhood experiences. It recounts the story of a choir director in Maine who molests the boys in his charge, with dire consequences. The protagonist, a singer and swimmer nicknamed Fee, suffers a cavalcade of losses as those closest to him succumb to the trauma of abuse.

Like the Rhode Island-born Chee, Fee is gay and Korean American. (Chee’s late father was Korean with Mongolian and Chinese ancestry. His mother is Scotch Irish, Irish, and Welsh.) In the essay “The Autobiography of My Novel,” Chee says Edinburgh was rejected 24 times in the course of a two-year submission process. When Welcome Rain Publishers finally published the book, reviews were glowing. The novel won the James Michener/Copernicus Society Fellowship Prize, the Lambda Literary Foundation Editors’ Choice Award, and other honors.

The Queen of the Night, published 15 years after Edinburgh, represented a dramatic shift in both subject and style. “My editor said, ‘You only write your second novel once, thank God,’ ” says Chee. “I think it’s hard for a lot of people.” He did extensive research for the book, immersing himself in biographies, historical monographs, and French novels in translation, and agonized over the novel’s complex structure. “It was like intellectual spelunking,” he says, “and there were caves you could get lost in.”

The current essay collection was spurred, in part, by a 2015 invitation to read his work in Columbia University’s nonfiction program. “Everyone else in the series had a book,” he says, “so I felt a little self-conscious. I started thinking it was time for me to have my own book.”

From about 70 published essays, he culled 10, adding another half dozen that he had yet to complete. He revised the essays to avoid undue repetition and assembled them more or less chronologically. The collection is “like a shadow” of Edinburgh, he says, material that never found its way into the novel. The linked themes of masks, disguises, identity, and exile recur. Among the new book’s revelations is that Chee refrained from telling his mother about the sexual abuse he suffered as a child until the eve of his first novel’s publication.

Married to Dustin Schell, his longtime partner, Chee splits his time among an apartment in New York City, a house in the Catskills, and an apartment in Bradford, Vermont, about 25 miles north of Hanover. His current literary project is a return to his AIDS activist characters, destined to become either a novel or a set of linked short stories, he says.

Between 1988 and 1990, Chee says he read only female writers, to avoid “being someone who relied too much on male privilege.” He considers the #MeToo movement “an overdue reckoning” that nevertheless “places a burden on all of us who teach. It makes every interaction something that you can sometimes second guess. You have a meeting with the student and the door closes, you forget to go back and open the door—that alone can haunt you for days.

“I take my students very seriously,” he adds, “and I know they take me seriously, too. It’s hard for me to have sympathy for people who don’t respect that relationship. You’re trying to offer students the tools to become themselves. And if that’s not what you’re doing, what are you doing?”

Julia M. Klein is a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and other publications.