Students often ask me whether I think they can be a writer. I tell them I don’t know. Because it depends, first and foremost, on whether you want to be one. This question is not as simple to answer as it seems. The difficulties are many, even if you truly want to be a writer. What seems to separate those who write from those who don’t is being able to stand it.

Students often ask me whether I think they can be a writer. I tell them I don’t know. Because it depends, first and foremost, on whether you want to be one. This question is not as simple to answer as it seems. The difficulties are many, even if you truly want to be a writer. What seems to separate those who write from those who don’t is being able to stand it.

“I started with writers more talented than me,” Annie Dillard had said in the class I took from her in college. “And they’re not writing anymore. I am.” I remember, as a student, thinking, Why wouldn’t you do the work? What could possibly stop you?

I began teaching writers in the fall of 1996, at a continuing education program based on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. I called it the MASH unit of creative writing because you can’t turn anyone away from your classes there. The program pays instructors what it has always paid them, even now, twenty years later, and they do so because there is always an M.F.A. graduate like me who needs a first teaching job, and every other place that offers writing classes in New York is more or less like this. But I loved my students, and what I still value of this experience is that it was there that I first discovered that good writing was, as Annie had said to us, very teachable. Talent mattered less than it was made to seem to matter. I watched in my first classes as I applied techniques I’d been taught to students who seemed at first to be unlikely writers and they turned into excellent ones. I learned a different kind of humility there in the face of their efforts, which I think still serves me as a teacher: You don’t know who will make it and who will not, and students’ previous work may or may not be an indicator of what they can do, good or bad.

Most of what Annie had taught me was about habits of mind and habits of work. As long as these continued, I imagined, so would the writing. I will always want my students to know that if what you write matters enough, it makes no difference where you write it, or if you have a desk, or if you have quiet, and so on. If the essay or novel or poem wants to be written, it will speak to you while the conductor is calling out the streets. The question is, will you listen? And listen regularly?

Teaching these classes I also learned what could stop a writer. So many of the students in my classes were stuck. Some were struggling with a story they both wanted to tell and had forbidden themselves from telling. Some were struggling with a family story that they believed, if told, would destroy their family, or them, or their relationship to the family.

Why does the talented student of writing stop? It is usually the imagination, turned to creating a story in which you are a failure, and all you have done has failed, and you are made out to be the fraud you’ve feared you are. You can imagine the story you might tell, or you can imagine this other story—both will be extraordinarily detailed, but only one will be something you can publish. The other will freeze you in place, in a private theater of pain that seats one. These writers were—are, in many cases—people who know how to write. What they don’t know is how to become unstuck. How to leave that theater they made for themselves, how to stop telling themselves the story that freezes them.

I discovered I needed to teach not just how to write, but how to keep writing. How to face up to who you think is listening. Is the person listening more important than you? Or is the story you would tell more important than you?

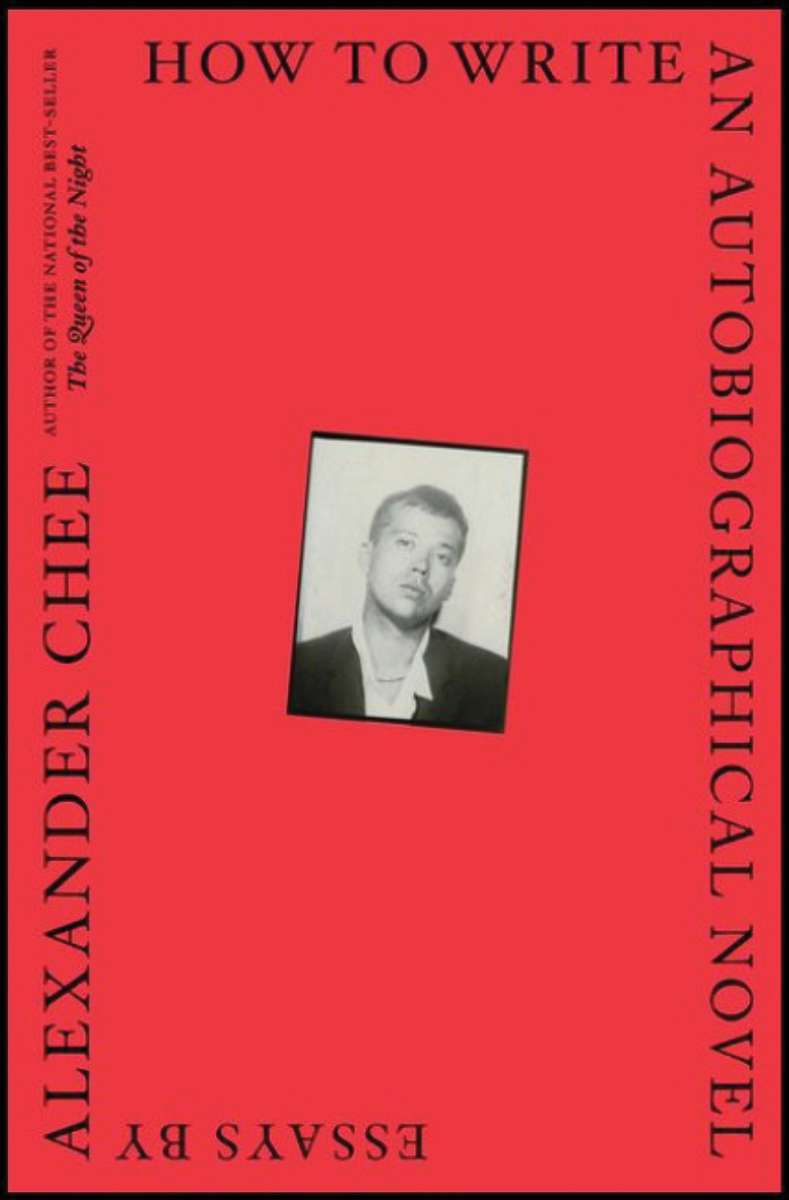

Reprinted with permission from How to Write an Autobiographical Novel by Alexander Chee. Copyright 2018, Mariner Books.