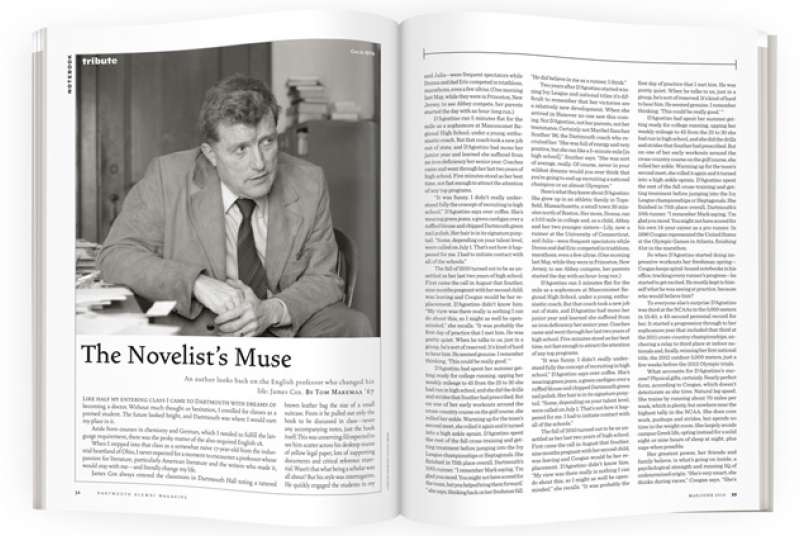

The Novelist’s Muse

Like half my entering class I came to Dartmouth with dreamsof becoming a doctor. Without much thought or hesitation, I enrolled for classes as a premed student. The future looked bright, and Dartmouth was where I would earn my place in it.

Aside from courses in chemistry and German, which I needed to fulfill the language requirement, there was the pesky matter of the also-required English 1A.

When I stepped into that class as a somewhat naive 17-year-old from the industrial heartland of Ohio, I never expected for a moment to encounter a professor whose passion for literature, particularly American literature and the writers who made it, would stay with me—and literally change my life.

James Cox always entered the classroom in Dartmouth Hall toting a tattered brown leather bag the size of a small suitcase. From it he pulled out only the book to be discussed in class—never any accompanying notes, just the book itself. This was unnerving; I’d expected to see him scatter across his desktop reams of yellow legal paper, lots of supporting documents and critical reference material. Wasn’t that what being a scholar was all about? But his style was interrogative. He quickly engaged the students in my class with sharp, probing questions about issues of race in Faulkner’s Light in August and existential choices in Hemingway’s Collected Stories. Hunched over his desk, elbows forward, with an occasional finger crooked in the air, Cox commanded our attention—and respect—with his booming Southern drawl, but he made it known that he wanted to hear what we had to say. He wanted us to react, at some gut level, to the assigned reading, drawing—if we dared—from the booty of our own limited experiences.

In class I noticed how Professor Cox liked to flip through the pages of a book, thumbing them casually as if somehow to feel the words kaleidoscopically on paper. A book, especially one written by a great American writer—Hawthorne, Melville, Twain among his favorites—was, to his eyes, a totemic object, a sacred work of historical and cultural importance that demanded involvement and response on the part of the reader. Yet such sacred works were not always to be taken with complete seriousness. In fact, what I remember most from those classes with Professor Cox was the humor that he employed with such dexterity in talking about literature. His was not a sardonic or wry kind of wit, but a humor that came right up from the gut. He got us to laugh about something we all knew yet had suppressed—for example, the true symbolism of Melville’s Moby Dick and Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, the sexual connotations and unspoken truths of the American experience.

It is probably no exaggeration to say that as freshmen most of us in his class were terrible writers, yet the man never ripped up our essays with heavy marginal comments or even assigned us didactically a specific literary topic. We were to read a book and simply write something about it, anything really, whatever we wanted. Our class papers could take any form we desired: a cogent essay, an autobiographical riff, a critical review. It was that freedom to react to a work of literature in any way we wanted—to trust our own instincts and observations about the world around us—that sealed the deal for me to become, eventually, a writer and not a doctor.

By the time I had taken my second Cox course he had vaulted to superstar status. His English 78 course, “American Literature of the 20th Century,” was overflowing with hundreds of students, not just English majors. It had become a lecture course, not the seminar I’d taken as a freshman, and it rocked the house. When he got up on the podium, still without notes or with simply a few bulleted items on a yellow sheet of paper, Cox roared with anecdotes, observations and a bevy of insights into the works of Dreiser, Lardner, Anderson, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Salinger and Nabokov. As before, he had the students in class rolling on the floor with laughter. Others joined me in attending these lectures just for the entertainment they provided.

Black humor reached its artful climax when Cox read aloud from the last page of Lolita in which Humbert Humbert offers his version of profound advice to Dolores Haze (Lolita) and her new husband, Richard: “While the blood still throbs through my writing hand, you are still as much part blessed matter as I am, and I can still talk to you from here to Alaska. Be true to your Dick. Do not let other fellows touch you. Do not talk to strangers. I hope you will love your baby. I hope it will be a boy….” As with Melville, we were in the belly of the whale, exploring its innards, deep in the guts of the American experience.

On receiving the Hubbell Award given by the American literature section of the Modern Language Association in 1997, Cox told the audience his “luck began early,” when he was born in 1925, “the year that saw publication of In Our Time, The Great Gatsby and An American Tragedy.” He went on to express his gratitude for the financial independence afforded him by the G.I. Bill after his service in the Navy.

He had “drifted into an English major,” he said, which is probably what happened to many of us at Dartmouth during the 1960s as late bloomers in search of enlightenment. Cox recalled that in the summer of 1952 he landed in Leslie Fiedler’s “Myth in American Fiction and Verse” course at the University of Indiana and chose American literature as his field. Cox earned his Ph.D. from Indiana in 1955. His career at Dartmouth continued until his retirement in 1990.

Living now on the Virginia farm where he was raised, Cox reads more voraciously than ever, inspiring me to carry on, in my own small way, the tradition of American literature that he introduced me to so effortlessly. Cox also continues to write. His work on Mark Twain, including a new edition of Mark Twain: The Fate of Humor (University of Missouri Press, 2002), emphasizes how and why Twain remains an important writer in the American canon of fiction.

As is clear from the long neglect suffered by Melville (until the Harvard scholar F.O. Matthiessen issued The American Renaissance in 1941, a book deemed by Cox to be the most influential of his academic life) and the fact that all of Faulkner’s novels had fallen perilously out of print before he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949, to write fiction is to cast your fate to the wind. To read fiction, however, as we learned in Cox’s freshman English class, is a choice that returns a rich harvest of pleasure and excitement for a lifetime.

Tom Maremaa is a software engineer in Cupertino, California. His most recent novel is Metal Heads (Kunati Books, 2009).