The Italicized Life of Frank Wilderson ’78

There is nothing like a pure revolutionary anymore in America, but Frank Wilderson is as close as you are going to get.

At 54, Wilderson is an award-winning author, founder of the Afro-pessimism movement and an associate professor of drama and African-American studies at the University of California, Irvine. Last year he received tenure, after nearly 20 years of teaching. He has produced one short film and written two books—one a memoir and one a film studies monograph that emerged from his Ph.D. thesis. (He also has two master’s degrees.) He is a public intellectual, a maven of ideas who publishes and lectures constantly.

He is not a parlor Bolshevik. In seventh grade in Chicago Wilderson led a civil disobedience campaign against the recitation of the “Pledge of Allegiance” at his parochial middle school. Result: ruler on palm, smack. In eighth grade he formed the dot on an exclamation point of a human-drawn phrase—“Off The Pigs!”—on a field at his Berkeley, California, school when the National Guard choppered in to put down riots at the University of California. Then he went to the Berkeley campus and joined in the riots. Result: tear gas, beaten with a rifle. At Dartmouth he led a protest against the treatment of immigrant workers on campus. Result: a two-year suspension. While getting his Ph.D. at Berkeley he led an unarmed occupation of a courtroom to protest a trial of six members of the Third World Liberation Front. Result: The six were freed, and Wilderson was arrested and charged with a couple of felony counts.

In the 1990s Wilderson lived in South Africa. People say, “Oh, what an exciting time to be there,” and he has to smile. He taught in underfunded community colleges. He investigated massacres. He joined the African National Congress’ military wing and served as an underground guerrilla.

The first question people ask him at literary readings: “Did you kill someone in South Africa?”

In his writings Wilderson brims with so much intensity that he can hardly plop a quotation onto a page without italicizing a word or phrase and then adding “[Emphasis mine].”

“Emphasis mine” is a leitmotif for Frank B. Wilderson III. He has never lived his life quietly, simply nestling into the status quo. He was born in New Orleans and, before moving to California, was raised in Ann Arbor, Michigan, then Minneapolis, Minnesota, the eldest of three children of a couple from Louisiana. Frank Jr. was a professor of educational psychology at the University of Minnesota. Wilderson’s mother, Ida-Lorraine, was a school administrator. In 1962 the Wildersons were the first family of color to move into Kenwood, a formerly all-white, affluent neighborhood in western Minneapolis, and young Frank was one of two black children in his public elementary school.

The touchstone of Wilderson’s childhood might have been seeing the physical results of state violence. In December 1969 in Chicago, where his father was on sabbatical, Frank walked through Fred Hampton’s apartment after the local police had shot and killed the Black Panther in his bed—no one sealed off the bullet-ridden crime scene for 13 days.

Able to quote long passages by memory from 20th-century philosopher and anticolonialist Frantz Fanon, Wilderson was not the typical freshman when he arrived at his Fayerweather dorm room in September 1974. For his freshman trip he signed up for the hardest hike possible, incurring blisters on his feet that lasted for weeks. For two seasons he played outside linebacker on the football team. As the title of his 2008 memoir, Incognegro, suggests, Wilderson has lived with a multilayering of masks and personas. Perhaps nowhere was this more obvious to him than in Hanover. “My sister had a completely different experience at Dartmouth,” Wilderson says. “She had gone to Breck [a private school in Minneapolis] and was prepared for Dartmouth’s complete concentration of power in white hands.” (Fawn Wilderson-Legros ’79 is an actress and attorney in Minnesota; Wilderson’s younger brother, Wayne, is an actor who has appeared in many films, including A Mighty Wind and Independence Day, as well as on Seinfeld.)

It was an intense time to be a politically active African American at Dartmouth, which had only a few years earlier begun matriculating significant numbers of black students. Wilderson spent many hours in the basement of the Afro-American Society house, now called Cutter/Shabazz, debating how to respond to the U.S. bicentennial. As a sophomore he became president of the Black Student Union. At the same time he backed out of the process of joining Alpha Phi Alpha, the historically black fraternity that started a Dartmouth chapter in 1972. Reggie Williams ’76, the captain of the football team and an Alpha, was nonplussed when Wilderson dropped his bid since all the African Americans on the football team were Alpha brothers. Wilderson eventually quit the team—“I found out my life didn’t depend upon being a football player,” he says—but ran into another problem. While on academic probation for a bad grade in physics he organized a rally in support of immigrant construction workers on campus who were being forced to eat at off hours and in a side room at Thayer. Hanover police arrested him for trespassing, and in February 1978 Dartmouth indefinitely suspended him. “My poor parents,” remembers Wilderson. “Their daughter was teaching French with John Rassias, wildly successful, and their son had E’s in science and was getting kicked out for politics.”

For two years Wilderson hitchhiked around the country, working as a day laborer, garbageman and freelance journalist. In March 1980 he returned to Dartmouth. “I had distance and didn’t get rattled like I had before,” Wilderson recalls. He majored in government, minored in European philosophy and worked on his writing with Bill Cook, the English professor and poet. He also wrote a long profile of Jim Loeb ’29, the political activist and ambassador, for this magazine. “I have this image of Frank in his green Army jacket and black beret, walking across the Green,” says Judith Byfield ’80, a friend at Dartmouth and later at Columbia. “He was a very nice person, not one of these guys who was too cool to talk to you. He was smart and very inspiring but approachable. A lot of people had little crushes on Frank.”

Wilderson’s curriculum vitae lists his awards and articles (“Gramsci’s Black Marx: Whither the Slave in Civil Society?”), but there is almost nothing in the eight pages about the 1980s. For seven years he was a stockbroker. In archetypal terms, this was his period of exile and excess—exile from his true calling and the excess that comes with flying on planes that have real china. He was the first black stockbroker in Minneapolis.

He was probably the only Marxist one. “I lived a double life,” Wilderson says. He was quietly writing a novel about two Dartmouth men who travel to Africa (Wilderson has written three unpublished novels, now stored in boxes in his garage), teaching creative writing at night and leading an ad-hoc political discussion group at the University of Minnesota. “I remember when I first saw him, this stockbroker in a three-piece suit,” says Charles Sugnet, a professor at the University of Minnesota and colleague from that time. “He came into the English department with this manuscript and we became friends. He had a magnetic personality.”

At age 33 Wilderson quit his job and applied to Columbia to pursue a master’s in fiction writing. Just before starting he went to South Africa to research his next novel. Within 24 hours he got into a race-related brawl at his bed-and-breakfast and met a law school student, Khanya, to whom he would become engaged within months and then marry. For two years they endured a transatlantic romance until he graduated from Columbia and moved to Johannesburg.

In South Africa Wilderson was in heaven: a country on the verge of a revolution. For the next five years he wrote articles and spoke on radio and television shows and at conferences, worked as a dramaturge at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg (something he’d done previously at Lincoln Center in New York City) and taught creative writing and cultural studies classes at two universities and a post-secondary community college.

He lived a Spartan existence, especially compared to other American expatriates. He and Khanya and her baby girl (from an earlier relationship) lived in apartments occupied primarily by working-class blacks. “He wasn’t one of those high-powered academic tourists who camped out in eight-bedroom houses with swimming pools and four domestic workers,” says James Kilgore, the director of the community college where Wilderson taught. He didn’t have a car. He waited tables in between teaching gigs. Ironically, Wilderson showed up for his interview at the community college wearing a coat and tie, which almost disqualified him. “We were an organization of the struggle, not prone to wear the attire of the ‘bourgeoisie,’ ” Kilgore says. “But Frank had a great enthusiasm for the struggles of local people and a very nuanced political understanding.” He spent hours after class, Kilgore remembers, surrounded by students as he lent critical theory books and discussed the politics of the day.

Politically, it was exhilarating. Wilderson was elected to the Transvaal executive committee of the Congress of South African Writers and numerous committees at his universities, even leading a strike. He also joined the African National Congress (ANC), and in July 1992 was elected to the executive committee of the ANC’s Hillbrow district—the equivalent, he likes to say, of being on the executive committee of the Democratic Party’s Harlem branch. In perhaps the most moving scene of his memoir, Wilderson describes how he investigated massacres as a field worker for an ANC peace commission, risking his life in war-torn squatter camps.

At the same time he moonlighted as an urban guerrilla. Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the ANC’s military army, recruited Wilderson into a unit, and he carried messages, harbored witnesses to atrocities, ran arms to and from dead letter boxes (arms caches) and safe houses, interrogated informers and compiled files on academics and visiting Americans. He trained with an AK-47. Much of Incognegro seethes with the tension from this clandestine period. The ANC was unsure whether it was a truly revolutionary movement or willing to stay within the confines of Western, liberal capitalism. Allegiances changed overnight. Many MK units, such as Wilderson’s, refused to demobilize. No one was who he seemed to be. Even Kilgore had a secret: He was on the run from U.S. federal charges relating to his years in the Symbionese Liberation Army. (Kilgore was arrested and extradited in 2002 and served five years in jail.)

It was real stuff, and Wilderson doesn’t romanticize it. He had guns pulled on him. His relationship with his wife and stepdaughter frayed, and he and Khanya separated and eventually divorced. His unit went on an assassination mission—grenades, machine guns—in the West Rand district after the murder of Chris Hani, the former commander of MK and ANC president Nelson Mandela’s potential successor, in April 1993. The police arrested and tortured a couple of his comrades. Disturbed at political developments, Wilderson confronted Mandela at a Johannesburg hotel just before the historic 1994 elections that made him president of South Africa, causing Mandela to later declare that Wilderson was “a threat to national security.”

Wilderson demobilized in 1996. He crashed on his brother’s couch in Los Angeles, found work as a substitute teacher in Compton, California, and then headed up the coast. For the next decade he worked on his Ph.D. in the film studies program at Berkeley and bounced among teaching jobs. As in South Africa, he was fired from some jobs and made unwelcome at others because he was willing and eager to confront racism head-on. He condemned colleagues, friends, even the adult daughter of a girlfriend; he drove his dissertation advisor to tears.

He was also writing a memoir. Following the model of Black Panther activist Assata Shakur’s groundbreaking 1987 autobiography, Wilderson eschewed a straight chronological telling. The scenes shifted from Minneapolis to Johannesburg to Berkeley, California, all in one chapter. Ever nonlinear, Wilderson spliced in letters, e-mails and memoranda he wrote, and reproduced “journal” entries (though he doesn’t hide the fact that they are rewritten). His searing poetry serves as an epigraph for each chapter. It is a political book not without emotion: Both “white” and “black” are capitalized; “dad” is not, which is telling after Wilderson describes a beating his father administered.

In 2003 Wilderson finished a 200,000-word draft of Incognegro and entered publishing purgatory. He almost sold it to Palgrave, which gave a verbal offer, but the deal fell through at the last minute after a battle between editors and publishers. He took it to Beacon Press. There he got an advance, and editors cut it down to 170,000 words and put it in the spring 2007 catalog. Then Beacon rescinded the contract, ostensibly over the length of the book. Wilderson then, for the second time in his literary career, fired his literary agent.

Making one last try he posted the manuscript to 50 publishers. Jocelyn Burrell at South End Press received it. “I read it in about a day and a half,” she says. “I stayed up all night. I read it on the train. I was absolutely fascinated and stunned. It was very devastating, very intriguing, very captivating. I was immensely excited about the kinds of questions he was raising, the risk-taking. I hadn’t seen a work that had taken apart the contemporary hydraulics of relationships in academia or in private so completely. It was damning and revelatory. There was something about naming and being willing to name it. It was hot, hot to the touch. It is a book that indelibly changed me as a reader. As an editor, I hope to have one this good every 10 years.”

A progressive, nonprofit collective—the motto stamped on the spine of each book is “Read. Write. Revolt.”—South End publishes political books, not memoirs, especially not 170,000-word memoirs. But, powered by enthusiasm for the book, South End slashed its usual production schedule in half and published Incognegro: A Memoir of Exile & Apartheid in just six months. It appeared in August 2008 as a 500-page paperback in a 6,000-copy print run.

For such a small book from a small press, the reaction was incredible. It won a 2008 American Book Award and a 2009 Legacy Award from the Zora Neale Hurston/Richard Wright Foundation and helped earn Wilderson a National Endowment for the Arts literature fellowship. Wilderson was asked to give readings in more than two dozen cities around the country. At events he often screened his film Reparations…Now, a 25-minute film consisting of a Spalding Gray-ish monologue along with tightly edited interviews about racism—it never overtly mentions reparations. The book reviews were often ecstatic. Kirkus called it “long-winded, but frequently beautiful…angry and paranoid with moments of stylistic clarity.” Publisher’s Weekly didn’t like the “distracting digressions” but enjoyed Wilderson’s “stinging portrait of Nelson Mandela as a petulant elder eager to accommodate his white countrymen.” Morgan State professor Todd Burroughs loved it: “By willing to leap, bloody sword in hand, into contradictions most black people happily chose to ignore, the author shows a dangerous level of self-awareness and honesty that has led many of his scribe-tribe to madness or deep cynicism.” Some people became so engrossed in the book they missed their subway stops. Others found it deeply troubling, and berated Wilderson at readings. “Many said, ‘You can’t talk about the black community, you can’t talk about our family, you can’t do this to us,’ ” he says.

In spite—or because—of its controversial message, Incognegro is destined for a long shelf life. The novelist Ishmael Reed predicted that Wilderson will become a major American writer. “It is going to be a part of the canon of African-American literature,” Charles Sugnet says. “I have students already writing honors theses on it. It is on a lot of reading lists. It is a stunning book.”

Four years ago Wilderson and UC Irvine colleague Jared Sexton held a symposium that more or less launched Afro-pessimism. A movement stemming partially from the works of cultural theorists such as Franz Fanon, Afro-pessimism has become a galvanic part of African-American critical theory with Wilderson as its standard-bearer.

Afro-pessimism is bleak: Blacks are nonhuman, without kinship, subject to gratuitous terror and violence and exploitation. Black family, Wilderson writes, is an oxymoron. Slavery did not end in 1865; the prison has replaced the plantation. The shorthand he tells his students is, “Question: Why was the worker shot? Answer: Because s/he went on strike. Question: Why was the black shot? Answer: Because s/he was there.” The only resolution for African Americans is a “disconfiguration of civil society,” he contends. “Checkers pieces cannot invade a chessboard,” Wilderson wrote to me, “without—and this is key!—a paradigmatic disintegration of chess and all its coherence.” Thus, even something as radical as the prison abolition movement is deemed accommodationist.

In Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms, published in March by Duke University Press, Wilderson used Afro-pessimism to parse four films: Bush Mama (1979), Monster’s Ball (2001), Skins (2002) and Antwone Fisher (2002). The critique is incredibly dense, strewn with words only academics use with straight faces—aporia, imbricate, vestimentary, acephalic, idiopathic, interpellate—and sentences that seem willfully unreadable. But it is nonetheless compelling and disturbing. For example, Wilderson notes that Denzel Washington has played a police officer seven times. “Few characters aestheticize white supremacy more effectively and persuasively than a black male cop,” he writes.

What would an Afro-pessimist do if he were a trustee of Dartmouth? It is surely a leading question, and after twice demurring (“one of the things I gave myself for my 50th birthday was permission not to answer policy questions”) Wilderson says that he would push liberal reforms, not fooling himself “into thinking this had anything to do with black liberation.” Then he makes an interesting point: “I think students at colleges like Dartmouth are taught to solve problems, and that they are strong and accomplished individuals. They are limited in their capacity to wallow in the contradictions of social unrest, the asymmetries of relations of power at a structural, paradigmatic level. They also often leave schools like Dartmouth feeling entitled. This does not bode well for producing future agents of change.”

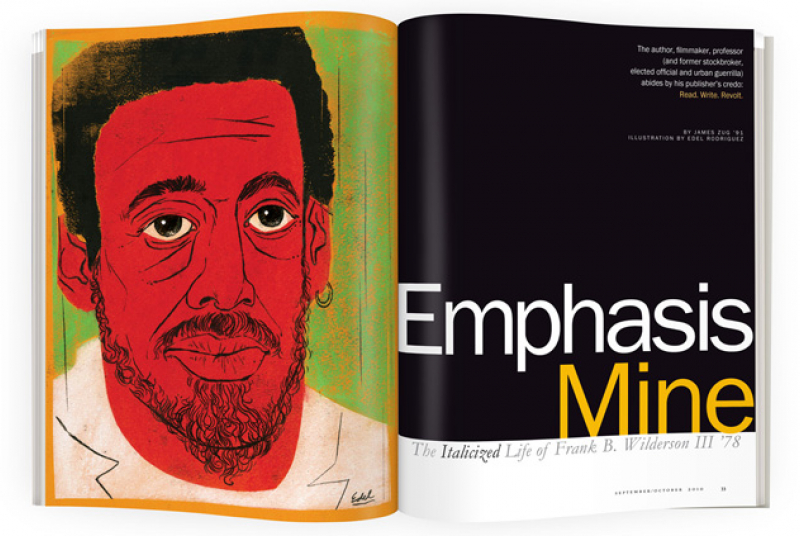

Wilderson pursues revolution with the most disarming of personalities. He stands just under six feet tall. He has a goatee that sprays out below his chin in a grayish whirl, an earring in the lobe of his left ear. He hugs people he’s never met before. He is a laugher—warm, sometimes almost girlish in his giggling jubilance. Unless a cackle emerges first, he pauses before he speaks, and he speaks slowly in a bass voice that quivers with empathy. He does not hold forth. He does not interrupt. He has an empirical temperament and is able to reel off facts and theories, and the facts are yoked to reality, to a bare dirt floor or a prison cell. He writes his first drafts in longhand. He meditates. He reads for pleasure (he tackles Proust yearly). He listens to jazz. He doesn’t watch television.

“He is, socially, an enormously charming person,” says Reynolds Smith, his editor at Duke University Press, “and, as a white person myself, I don’t have a more charming author of any race among the many hundreds of authors I have had over a 34-year career.”

At heart though, Wilderson is not so much a professor or philosopher or activist as a creative writer. It is his first love. He has written poetry since he was 9 years old, short stories since he was 12. At Columbia he studied fiction writing with renowned teachers such as novelist Mary Gordon. It was a full-time occupation, but it wasn’t enough, so he took night classes downtown at the New School, doing a stream-of-consciousness workshop. “I was going to school all the time,” he recalls.

Noting that insurance actuarial tables predict his death in 12 years, Wilderson says he wants “to make my mark in the realm of imagination, theory and revolution”—in that order. He spent last summer in the L.A. Writers Lab speedwriting a first draft of his next novel. “This is the direction,” he says, “that I really want my life to go in.”

Fiction is also a salve when reality continues to reject his efforts. “I don’t think I am someone who can or should press the moment,” he says. “I write what I know and participate if something comes by. It’s dangerous to be volunteeristic. It’s dangerous to cajole political action when the people on the ground are not ready. I try to keep ‘protracted’ in front of the word ‘struggle’—I said that a lot as a child. I want radical revolutionary change to happen when I am alive, but that is not a good enough reason.”

James Zug is the author of Run to the Roar, due from Penguin in November. He lives in Wilmington, Delaware.