Jeffrey Hart, who died in February, contained multitudes. A professor of English as well as a senior editor at National Review, a speechwriter for Presidents Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, and the founding advisor of The Dartmouth Review, he embraced contradiction. He was a conservative who turned away from ideology—and away from the Republican Party, in the end—to look to the lessons of literature and history to map out his political path.

The realities of Hart’s own experience could make their own fiction. In When the Going Was Good!, his 1982 paean to the 1950s, Hart wrote frequently of his own upbringing: The 1930s wrecked the family fortunes. Hart’s father, Clifford, class of 1921, was an out-of-work architect who taught in public schools. His mother, who danced and sang in the great musicals of the 1920s and once “rode on a swing in one of the Ziegfeld Follies,” settled the family “in a thirty-five-dollar-a-month apartment in Queens.”

Hart was a child of the Great Depression, but he lived life like someone out to restore the Roaring Twenties. America is a “willingness of the heart,” he liked to quote from F. Scott Fitzgerald. On the grass courts of the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, Hart found his proving ground. Tennis became “an activity to which I totally committed myself during my most impressionable years,” he wrote. “Beneath the off-white, monogrammed polo shirts and cable-stitch sweaters, there beat the fierce heart of a Cromwellian.”

Tennis took Hart from Stuyvesant, N.Y.C.’s great specialized high school, to Dartmouth, where he aced the varsity team and burned out the coaching staff. Since the age of 5, Hart had attended every Dartmouth-Princeton football game. He liked to say he was enrolled in the College since birth, but as a student he found the postwar campus more concerned with social than academic life. So he dropped out to write fiction and landed a job with a publisher back in New York City. Through the city’s literary scene, he connected with professors at Columbia and enrolled there as an English major.

Hart liked to say he was enrolled in the College since birth.

After four years in Navy intelligence during the Korean War, Hart returned to Columbia to earn his doctorate, specializing in 17th- and 18th-century English literature. He found himself on Columbia’s fast track, but his tenure chances were derailed when he started writing book reviews for National Review. His mentor, essayist Lionel Trilling, tried to convince Hart to quit the publication. Instead, Hart returned to his father’s alma mater, joining the English department at Dartmouth in 1963. When he became National Review’s senior editor in 1969, Hart began flying to New York City twice a month for editorial meetings and dinners with founder and editor William F. Buckley Jr. Hart stayed in the smallest room at the Yale Club and kept his typewriter in a gym locker.

Back at Dartmouth, Hart ran administrators and fellow faculty around the court of public opinion. He wrote a twice-weekly syndicated column that appeared in 500 newspapers. He was given Buckley’s old stretch limousine and parked it in front of Sanborn Library, taking up multiple spaces. When his son, Benjamin ’81, was an undergrad, he and other disaffected writers from The Dartmouth founded their own independent newspaper. When Dinesh D’Souza ’83 became its student editor, he lived for a time at the Hart home. “More or less, The Dartmouth Review was launched in the living room of my house,” Hart wrote. He served as its advisor for the rest of his life. “One definition of good journalism is printing things that someone does not want printed,” he said of the outspoken publication.

Through 30 years of teaching (1963 to 1993) and well into his retirement, Hart cast a larger-than-life presence over campus. “To be Jeffrey Hart’s student was to be initiated into the culture of the West by an unashamed partisan,” wrote conservative blogger Scott Johnson ’73. Hart checked his politics at the door and let the lyricism of “books, arts, and manners” lead the way for students. “In all of his courses Hart stressed two skills, reading and writing,” says Peter Robinson ’79, a Hart student who went on to craft Reagan’s exhortation to Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall.” “Do your reading. Experience the characters the author presents. Enter his world.”

The Making of the American Conservative Mind, his 2005 history of National Review, proved to be Hart’s last grand statement. It also announced his most unexpected change of game. The book was meant to be a promotional vehicle for the publication at the height of the Iraq War. Yet Hart concluded it with an attack on President George W. Bush, calling him the “bottom among American presidents” in the original manuscript, language that was softened before the final printing. The statement signaled a break with conservative colleagues, whom Hart considered to be in lockstep with the Republican Party. “I suppose I have always been a conservative of some sort,” Hart wrote in When the Going Was Good! Yet in his final years, he campaigned for Barack Obama and embryonic stem-cell research.

The Hart-break was an early indicator of the breakup of conservative consensus. What began in fusion ended in fission, with Donald Trump emerging from the wreckage of the Republican establishment. Hart’s young protégé, Joseph Rago ’05, the brilliant Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist who died just 12 years after his graduation, called Hart’s dissent “the most rigorous, utterly principled, and intellectually stimulating ever set down.”

Hart believed that argument restored culture from the forces of entropy and egalitarianism. “The goal of intellect is always there: cognition, the self-cleansing act of trying to see the object of knowledge as clearly as possible,” he wrote. Hart strove, in the words of poet and cultural critic Matthew Arnold, “in all branches of knowledge, theology, philosophy, history, art, science, to see the object as in itself it really is” and to teach us how to see it for ourselves.

James Panero is executive editor of The New Criterion. Read Panero’s 2007 profile of Hart in the DAM archive.

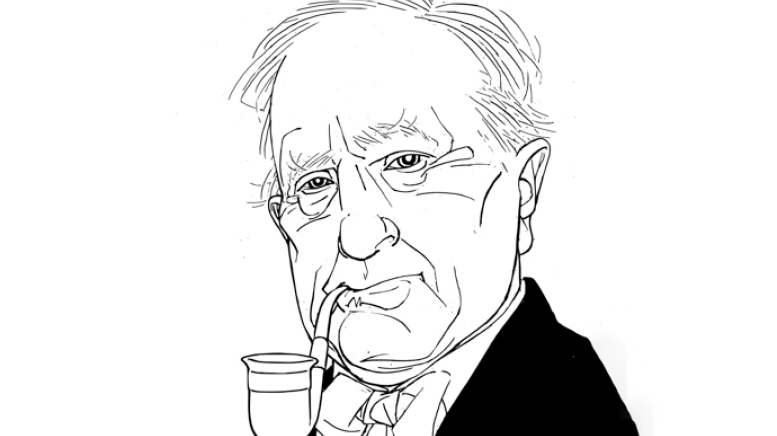

Illustration by David Johnson