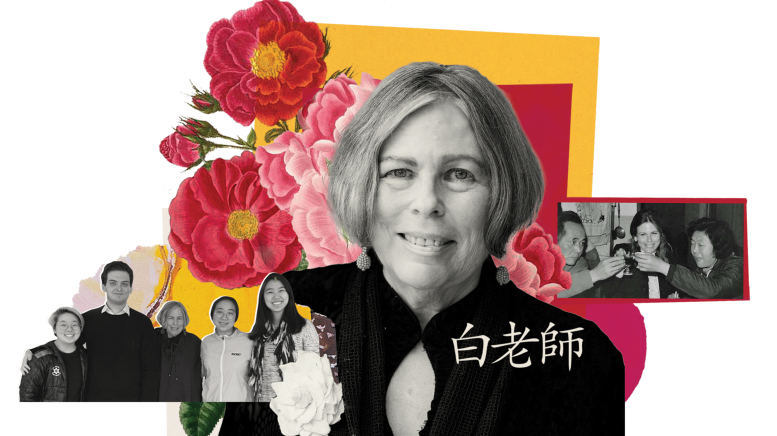

“Bo … po … mo … fo,” my wide-eyed freshman classmates and I obediently repeated in a sing-song chorus to the woman at the head of our Chinese 101 class—small in stature, dressed in all black, and very, very serious. Again and again, we tried to mimic sounds we had never heard, much less spoken. As the weeks passed in Bartlett Hall, she raised the bar by layering on four distinct tones to be applied to each sound. The differences between them were maddeningly subtle to our untrained ears and endlessly frustrating. But the woman at the head of the class—Susan Blader, whom we had learned to address as “Bai Laoshi” (Teacher Bai, or 白老師)—did not relent.

She patiently corrected our frequent mistakes but remained demanding. “This is nuts,” I thought to myself in frustration late one Thursday night, cramming for our weekly quiz while my roommates slept.

We would soon learn the method to her madness.

Bai Laoshi, who was born in 1943 and died last October, was a stickler for proper pronunciation and tone. Her demands extended beyond her classroom. She assigned mandatory hours in the language lab and actively oversaw our early-morning drill sessions, during which upperclassmen—using Professor John Rassias’ famous foreign language acquisition method—would spend an hour each day snapping their fingers at us, forcing us to think and respond spontaneously in Chinese. She also hosted her famous weekly “Noodle Hour,” when we would gather to eat packages of instant ramen and practice our fledgling language skills.

“Anyone can memorize characters,” she once told me, “but an authentic accent is priceless.” We had to work harder than most, but we were repaid a thousandfold by the looks of pleasant surprise from native speakers upon hearing us speak.

At the beginning of our second term, once she had come to know each of us, Bai Laoshi convened what she called the “Naming Ceremony,” an annual rite of passage for her first-year students. One by one, we were called forward to receive our new Chinese names. “Bai Laoshi developed an insightful understanding of each student’s personality, which then formed the basis of the Chinese names she bestowed upon us,” remembers Peter Adams ’88. “She also crafted our names to sound authentic and even elegant, at least in the opinion of my native-Mandarin-speaking partner, who has heard a number of them.” This was her second gift to each of us—one we still carry today.

Bai Laoshi had no children, but she mothered her students as if we were her own. So, she fed us—often. Chinese New Year, gatherings at the Asia House, and her dumpling-making sessions were all filled with delicacies she prepared by hand, each meal accompanied by lessons in Chinese culture and etiquette. “It is hard to remember Bai Laoshi without thinking about food,” recalls Chris Armacost ’88.

Her memory never faded; she remembered every detail about each of us, as any good mother would.”

Her care extended well beyond the culinary. Andy Field ’91 remembers, “One time when I was sick in Dick’s House with a fever, she came over to visit me and brought me a bagel—and my Chinese exam to complete.”

In hindsight, we, her students, felt a subconscious sense of filial piety in return. You simply did not want to let her down. One of her students, an accomplished athlete, was struggling with the coursework. She called him into her office midway through the term and asked what would happen to his performance on the field if he missed practice. That was all he needed to hear. He went on to become one of the hardest-working students in the department—and one of the finest Chinese linguists Dartmouth ever produced.

And then, just like that, she gently pushed us out of the nest. After three terms of Chinese—endless flashcards, countless hours in the language lab—we left for a summer of intensive language study abroad at Beijing Normal University in China or the inter-university program in Taiwan. We were well prepared but quickly discovered how deep the waters were and how much more there was to learn. For many of us, those three months abroad were life changing. I, for one, would never be the same.

After we graduated, many of us through the years would make pilgrimages to East Thetford, Vermont, where Bai Laoshi lived with her husband, Ehud Benor, also a Dartmouth professor. We would sit on her back deck, surrounded by an array of bird feeders, reminiscing about the old days and sharing updates on our families. Her memory never faded; she remembered every detail about each of us, as any good mother would.

Today, her brood is spread far and wide. Many live in China, Taiwan, or elsewhere in Asia, having tied their professional and personal lives to the region. Others came back to the United States but retain a lifelong appreciation of Chinese language and culture. No matter where we are today, we are connected by our days in Bartlett Hall—and by our love for the teacher who so profoundly shaped our lives. I cannot imagine a better legacy for an educator.

David Downie is an associate general counsel with Bank of America who lives in New Jersey.