When he called family members in Israel to make sure they were all right on October 7, 2023, Lance Kramer had not expected to start filming a feature-length documentary. Hamas had just attacked the Israeli communities bordering Gaza, killing or abducting close to 1,500 people. It soon became apparent that Kramer’s second cousin by marriage, Liat Atzili, was missing from her home in Kibbutz Nir Oz, along with her husband, Aviv. All the family knew was that Aviv had gone out early that morning to defend his home, while Liat was hiding in their safe room. The last sign of life was a distressed phone call from Liat at 11:30 that morning.

Lance and his brother, Brandon, who together run a documentary production company, were close to Liat’s parents, Yehuda and Chaya Beinin. The brothers had lived at the Beinins’ house during a previous visit to Israel.

When Kramer called Yehuda a few days later to offer support, Liat’s father suggested something unexpected. Yehuda was distressed because he felt the media was distorting his family’s narrative to support Israel’s fierce counterattack against Hamas. He proposed that Lance and his brother film the plight of the family as they grappled with how to secure Liat and Aviv’s release from Hamas captivity. The two brothers dropped everything to start filming—Lance as producer and Brandon as director.

Within three weeks, Yehuda was in Washington, D.C., to enlist American support. He was convinced that the hostages were not a priority for the Israeli government, and Yehuda and Chaya, who had emigrated from the United States to Israel in 1973, hoped their American dual citizenship would make a difference. Since the brothers are based in Washington, they were there to film as Yehuda navigated Capitol Hill to appeal to President Biden, members of Congress, and anyone willing to listen.

I hope the film offers a window into the complexity of the situation.”

—Lance Kramer ’06

“Initially, we thought we’d film for just a few days,” says Kramer. “But the situation unfurled very quickly and was much more complex than anything we could have ever imagined.” For Kramer, who minored in film and majored in history with a focus on Middle Eastern studies, the documentary merged two interests from his Dartmouth days that he never thought would meet. “We were literally filming Middle Eastern history as it happened,” he says.

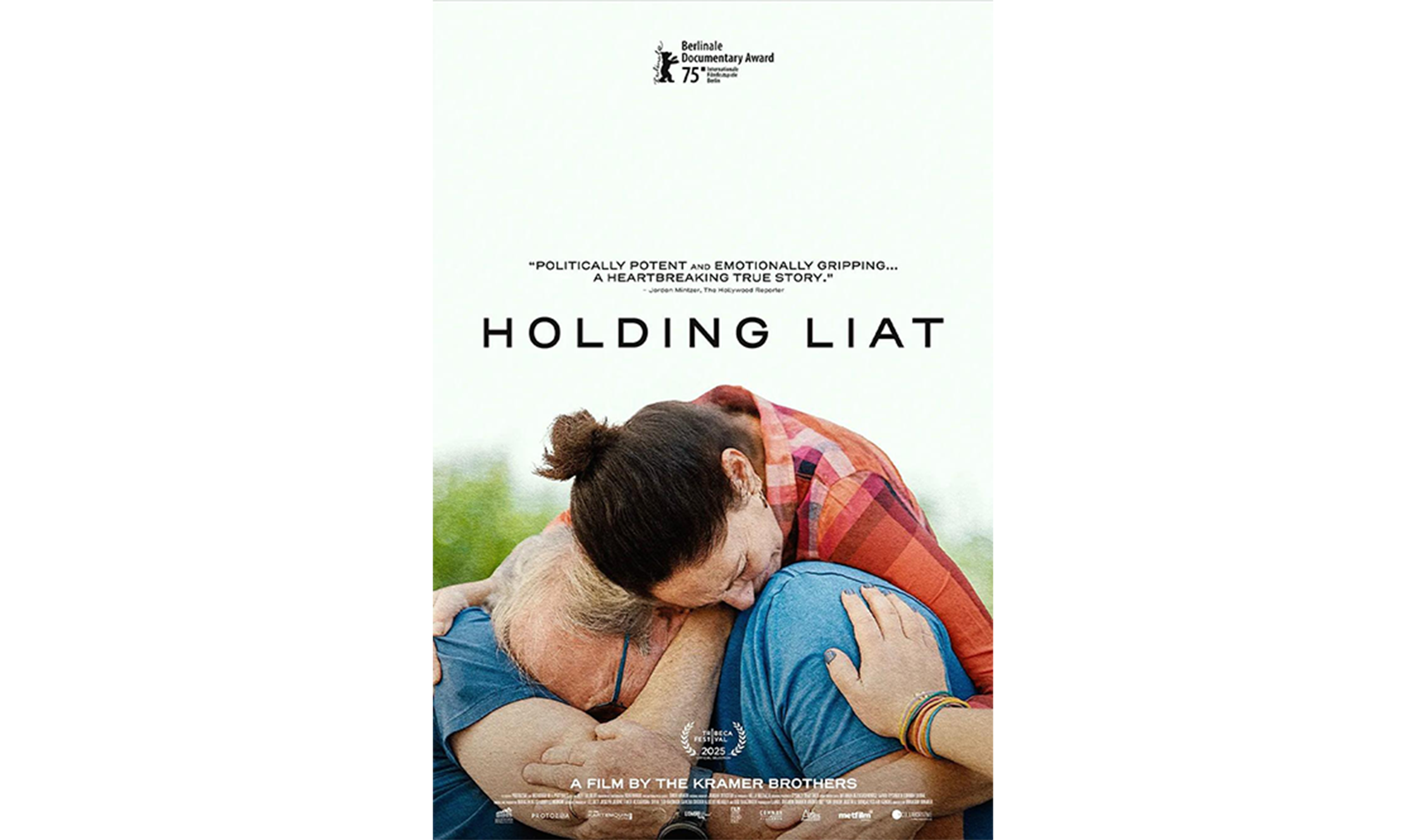

The brothers ended up with an award-winning documentary, Holding Liat, which depicts the journey of Yehuda and other family members through Washington’s corridors of power to get help for Liat and Aviv. Each family member reacts differently to the situation. Yehuda, steeped in leftist Zionist ideals, insists on promoting a message of peaceful compromise between Israelis and Palestinians as he lobbies for the release of his daughter and son-in-law. But Liat’s youngest son, Netta, who survived the attack by hiding for hours in his apartment as he heard his neighbors being killed, can’t forgive and calls for revenge against Hamas. Meanwhile, Yehuda’s brother, Joel Beinin, a professor of Middle East history at Stanford University and a founding member of Jewish Voice for Peace, reconciles support for his abducted Israeli niece with his criticism of the State of Israel.

“I hope the film offers a window into the complexity of the situation,” says Kramer. “And how, as human beings going through conflict and crisis, we all have different emotional responses that we must navigate.” Kramer particularly valued how Beinin-Atzili family members supported each other with love and compassion, even when disagreeing.

“In these divisive times,” says Kramer, “they offered an example of how to stay in relationship with one another despite differences.” Yehuda’s lobbying paid off. After 54 days of captivity in Gaza, Liat Atzili was released in a deal that President Biden helped broker. She was fortunate not to have suffered the abuse many other hostages experienced. Held at the home of a Hamas member, she was able to have conversations with her captors. They were eager to explain their worldview and why they had joined Hamas, while Liat, a history teacher who worked at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Remembrance Center, educated them about the Holocaust.

When Liat was returned to Israel, Brandon was with the family at the hospital to film the reunion as she embraced her parents, children, and sister, all of them laughing through their tears.

The day after her release, however, Liat learned that Aviv had been killed on October 7 and that Hamas was still holding his body. Despite her grief about her husband’s death, Liat refused to succumb to despair or a desire for vengeance. Within weeks of her release, she published an op-ed in The New York Times calling for reconciliation and a shared existence to secure a better future for both Israelis and Palestinians. A few months later, she spoke against the war in Gaza at a large Israeli-Palestinian peace conference and became active with The Parents Circle/Families Forum, an organization of Israelis and Palestinians who, despite having lost family members in the conflict, choose to channel their pain into promoting peaceful coexistence.

Not long after her release from captivity, Liat organized a funeral for Aviv that was captured on film. “It’s easy to fall into a place of loss,” she says, standing amid friends and family at the cemetery of the devastated kibbutz, “but I choose to hold on to all the things I got from Aviv, to his worldview and the way he lived his life.” She then invited the attendees to dance to his favorite song.

Holding Liat won the 2025 Berlinale Documentary Award and made the shortlist of 15 films for Best Documentary Feature of the 98th Academy Awards. The film was first released in the United States at the Film Forum in New York City on January 9 before being shown in other theaters nationwide.

Judith Hertog is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in DAM, The Atlantic, The New York Times, and Foreign Affairs.