Ernest Hemingway claimed he didn’t want any biography written about him while he was alive or for 100 years after his death. But Hemingway’s fourth wife and his publisher asked Carlos Baker to write an authorized biography shortly after Hemingway died in 1961. Baker’s monumental work, Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story, was published in 1969 and hailed in these pages as “one of the major literary events of the year.” A professor of literature at Princeton for nearly 40 years, Baker received an honorary doctorate of letters from Dartmouth in 1957. He died in 1987.

1

A former wife weighed in.

The New York Times praised the work as “a replica of Hemingway so real it moves,” while also expressing exasperation that, “Again and again, Professor Baker tells us how many trout or birds Hemingway killed on a particular day.” Another reviewer found the book “absolutely trustworthy,” but Hemingway’s third wife, Martha Gellhorn, didn’t agree. “Baker got everything wrong” about her life with Papa, she said, calling him “that tricky Carlos Baker.”

2

Baker took his time.

Baker spent seven years on the biography, slogging through trunks full of Hemingway’s outlines, drafts and unpublished manuscripts, including some that had been stored in the vault of the National Bank of Cuba (and used as security for cash advances from his publisher) and others in back rooms at Sloppy Joe’s Bar in Key West, Florida. He traveled to all the places Hemingway worked and played—from Walloon Lake in Michigan to the Plaza de Toros in Pamplona, Spain. Baker’s working papers and biographical files, stored at Princeton, take up 16.4 feet of shelf space.

3

As a class secretary, his notes sang.

At Dartmouth, Baker managed the ice hockey team and contributed to the Jacko. As an alum, Baker entertained as class secretary for five years and as class newsletter editor for eight. In his first Class Notes column he described a classmate’s “remarkable philoprogenitive achievement.” Another column, from January 1943: “As the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor whips past us like an ex-cab driver gleefully piloting a jeep….”

4

Fiction sprang to life.

“Back in college we all thought there was nothing finer than that tight-lipped passage [in A Farewell to Arms] when Lieutenant Henry left his girl, Catherine Barkley, dead in the Swiss hospital and walked back to the hotel in the rain,” said Baker. While writing his book, he met Agnes von Kurowsky, the former Red Cross nurse who was the inspiration for Barkley. She was “a lovely woman well past 70 and living (of all places) in Key West,” he wrote.

5

He mentored a notable protégé.

At Princeton, Baker advised undergrad A. Scott Berg, whose senior thesis, a biography of Hemingway’s first editor, became the National Book Award-winning Max Perkins: Editor of Genius. Berg, who won a Pulitzer for his 1998 biography of Charles Lindbergh, credited Baker for teaching him to conduct research without an assistant, using primary sources and “one note card at a time.”

6

Hemingway had previously read Baker.

The two authors never met, but the Nobel and Pulitzer winner considered Baker’s earlier study of his work, Hemingway: The Writer as Artist (1952), the best that had been written about him.

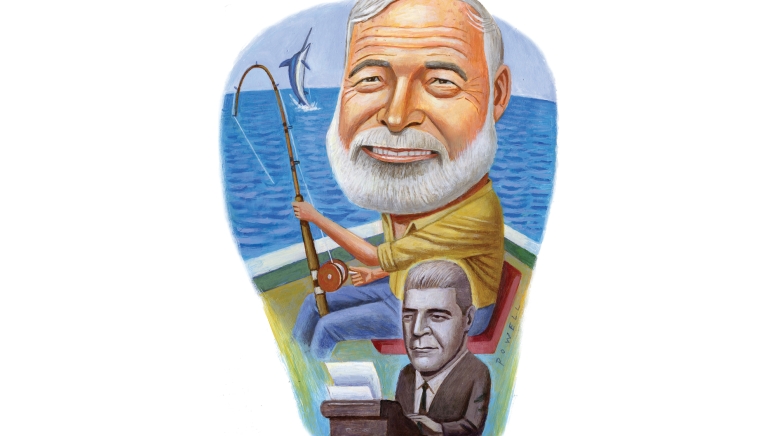

Illustration by Charlie Powell