Meryl, Overrated?

Movies that aren’t based on original screenplays are often adapted from books, magazine articles or newspaper stories. Writers, when they stumble onto a good location or a good story or good characters—or sometimes some of each—have been known to milk the material for all it’s worth, writers being, um, writers. It’s only natural. Farmers have the same appreciation for a chicken that reliably lays eggs. My story is such an instance, and I offer it, selflessly, as a textbook example of how a writer will shamelessly try to wring as many eggs out of one chicken as he can.

The chicken in this instance was a float trip down Montana’s Smith River in the summer of 1989. The first egg was a magazine article for Fly Rod & Reel called “Diary of a Mad Floater.” The second egg was a movie set on that very same river, but with a new name—The River Wild. The third egg will be a novel of the same title, based on that movie and written by yours truly, to be published in June. Let’s call this article a fourth egg—albeit out of sequence—intended to create awareness of egg No. 3. With any luck, the book—should anyone buy it—might entice someone into remaking The River Wild or making a movie sequel—either of which would be egg No. 5. I don’t want to screw the pooch, but I’d be lying if deep in my writer’s heart I don’t dream about egg No. 6 being a line of clothing.

Beeep. “Denis, it’s Meryl. Call me!” Beeeep. “Denis, where are you? It’s Meryl. I love your script. Call me!”

Once upon a time (in a period of history after the Civil War, before the Kardashians), we all had answering machines. A little red light would blink if someone had called, missed you and left a message. So it was on that fateful afternoon around 1992 when I hit the replay button and the voice of Meryl Streep—a short-term Dartmouth coed (she was a visiting student in 1970)—expressed enthusiasm for a screenplay I had written on spec and that had landed in her hands through her husband, Don Gummer.

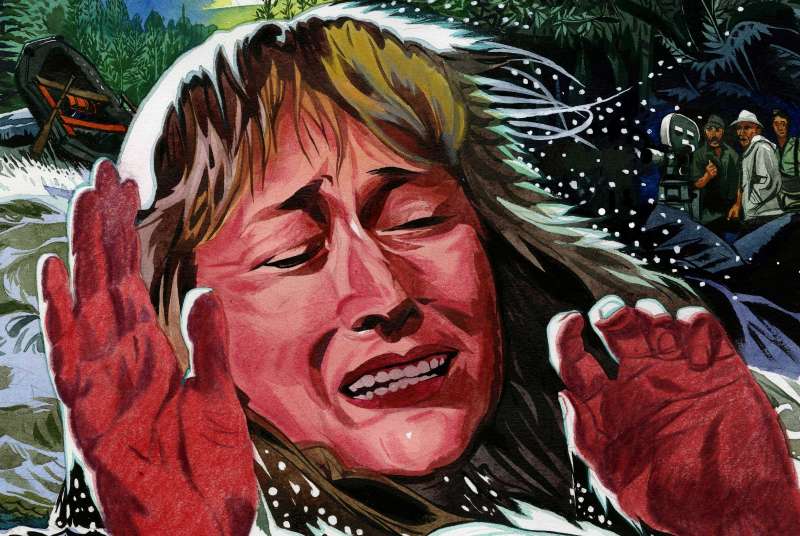

And then there was the afternoon the actress almost drowned in the middle of some angry water.

One thing led to another after that fateful phone call. It was all heady stuff for a born-and-bred New England boy. Since my West Coast transplanting in the mid-1980s, helpings of humiliation, seasoned with some success, had given me the confidence to impart to budding screenwriters advice I knew to be true: Something good might happen in the neon wilderness of Hollywood once you had a confluence of the “Three C’s”—craft, content and contacts. The River Wild was about the fifth screenplay I had written on a hope and a prayer, so my craft was improving. The content was inspired by the aforementioned float trip with some fishing buddies (a setup, I decided, that might lend itself to a darker story on a fictional River Wild). And the contact, in this case, was Meryl’s husband, whom I had met through my wife, who worked in the art world.

After director Curtis Hanson was added to the mix, and after a low-level bidding war, Universal landed the project and promptly replaced me with one screenwriter, then a pair of veteran screenwriters (none of whom shared a writing credit after a Writers Guild arbitration), who eventually filled Universal with enough confidence to green light the movie. Actors Kevin Bacon and John C. Reilly had also signed on, along with Meryl. Which is how I ended up on a small airplane in the summer of 1993, seated next to actress Kyra Sedgwick, Bacon’s wife, en route to Kalispell, Montana, where the cast and crew would be based for a chunk of the filmmaking.

At a communal buffet dinner under a tent in the week before filming began, Reilly sat next to me.(Doesn’t he know I’m only the writer?) He introduced himself and asked me to talk about his character, Terry, Bacon’s partner in crime in the story I had invented. On the written page he was a prison escapee, uncomfortable in the wilderness, bullied by Bacon’s psychopathic Wade. That’s about all I knew. I said as much to Reilly, but I could see he wanted to know more.

The only “more” I had was likening him to Lennie in Of Mice and Men—the gentle, powerful, mentally challenged field hand partnered with a smarter (Wade-like) mentor of sorts, George. That gave Reilly food for thought and me an exposure to the kind of character dimension a good actor wants to know about to dig into the role. It was a good writer’s lesson.

We ended up filming most of the movie in Montana. We created the fictional River Wild on three rivers: the Kootenai River and the Middle Fork of the Flathead River in Montana and the Rogue River in Oregon. The Kootenai was a good river wild—particularly a stretch outside of Libby, Montana, where it plunged through severe rapids and a gorge, forcing 27,000 cubic feet per second of water into a dangerous, rushing churn. It became the part of the river where we would film the climactic running of “the Gauntlet”—the end-of-movie sequence where Meryl miraculously survives a harrowing stretch of rapids rated “un-runnable” by whitewater standards.

The sequence would later be enhanced digitally, but Meryl and her two rafting doubles (whitewater aces Arlene Burns and Kelley Kalafatich) were in the raft for almost three weeks to secure the necessary footage for a 10-minute sequence. Meryl, by the way, probably did 90 percent of her own rowing—so fit and accomplished was she.

Two things I remember vividly. The actors got so cold working on the river, doing so many takes, that they often had to soak in hot tubs at the end of the day to restore body temperature. And then there was the afternoon Meryl almost drowned. The scene took place just below the major rapids. I was standing on the riverbank with the two producers, David Foster and Larry Turman, and director Hanson.

Meryl was below us, at the oars, in the middle of some angry water, momentarily anchored with Bacon, O’Reilly and Joe Mazzello, who was playing her son. As was customary when filming in these dangerous conditions, the movie’s river unit comprised the best whitewater rafters in the West, hovered downstream in various motorized vessels—just out of frame—ready to rush in, in case of trouble.

Satisfied everything was in place, Hanson yelled, “Action!” The anchoring cable to Meryl’s raft released, and she was on her own in perilous water. As she rose up for better leverage, one oar “caught a crab” and she was catapulted out of the raft, into the churning Kootenai River…and out of sight.

Freeze frame: The director, two producers and screenwriter peering at the dark waters of the Kootenai River as the river unit zoomed in to assist Streep, as yet unseen. If it had been a New Yorker cartoon, the bubbles over the four heads might have been: Director: “I wonder if I can use that shot of Meryl getting tossed?” Producer No. 1: “How are we going to finish the movie if she doesn’t pop up?” Producer No. 2: “Make a note to ask Universal to check its insurance policy.” Writer: “Oh f**k, my first movie and the star drowns?”

Meryl eventually surfaced, of course, and after a very long hot tub, she and the crew finished up filming in Oregon in October. Because some of the leaves had begun to turn, I remember seeing members of the production design team spray painting yellow leaves green, the suspension of disbelief requiring attention to detail.

Two postscripts: A year later, just before the movie was released in September 1994, I met up with Meryl. She’d just finished filming her next movie, The Bridges of Madison County, directed by Clint Eastwood. Movie directors have different methods of directing—Hanson liked to shoot dozens of takes, Eastwood just the opposite. “We’ll film a rehearsal,” Meryl told me, laughing, “and Clint would ask the actors if they were okay with it—if the director of photography was happy—and say: ‘Okay, let’s move on.’ ” They ended up shooting the entire movie in less time than it took us to shoot the harrowing Gauntlet scene on The River Wild.

Knowing what I know now, making even one memorable movie is hard to do. There is so much that has to go right, and it is well known that the movie gods do not recklessly dispense blessings. Hanson, who passed away last fall, made, in addition to mine, at least four memorable movies: The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, L.A. Confidential, Wonder Boys and 8 Mile. A remarkable achievement. Float in peace, Curtis.

Denis O’Neill lives in Beverly Hills, California. He is the author of Whiplash (2014). Click here for more info on his latest novel, The River Wild (2017).