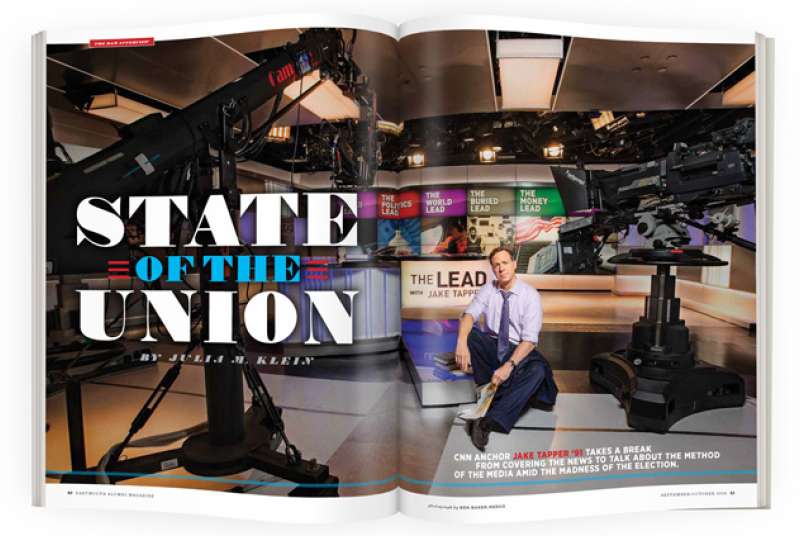

State of the Union

Even before Jake Tapper arrives, an email-checking, orange-eating whirlwind, his CNN office telegraphs his passions. Its glass entrance is bedecked with artwork by his two children, 8-year-old Alice and 6-year-old Jack. A sign paying tribute to America’s veterans reads: “Heroes don’t wear capes, they wear dog tags.”

Inside is a political junkie’s collection of campaign memorabilia, including a Florida butterfly ballot from the contested 2000 presidential election and prints, posters and photographs of losing presidential candidates from Henry Clay to Chris Christie. A framed letter from Gary Hart thanks 15-year-old Jacob Tapper for handing him a political caricature at a campaign appearance, offers a signed photograph and courteously declines a request for an interview for the high school newspaper. “I did finally get the interview,” Tapper notes. “It just took a while.” He grilled Hart three decades later, on his weekday show The Lead with Jake Tapper.

Persistence is a Tapper trademark. Headlines in June saluted him for following up 23 times when then-presumptive GOP presidential nominee Donald Trump tried to duck a question about whether the candidate’s criticism of a California federal judge was racist. As CNN’s chief Washington, D.C., correspondent, anchor of State of the Union and The Lead and the moderator of three GOP presidential debates, Tapper has repeatedly made news this election cycle with his tough-minded interviews.

Tapper’s route to journalism was a circuitous one. His first ambition was to be a political cartoonist—a skill he honed with his long-running Roll Call strip “Capitol Hell” and now exhibits in the “State of the Cartoonion” segment of his Sunday morning public-affairs show. After graduating from Dartmouth he worked as a staffer for Rep. Marjorie Margolies-Mezvinsky (D-Pa.) and later in D.C. public relations. The late David Carr, a former Washington City Paper editor who became The New York Times’ storied media columnist, was an important mentor, convincing Tapper to forsake better-paying PR jobs for the more amorphous rewards of alternative-weekly journalism.

After a stint at Salon.com, Tapper was able to make the leap to ABC News, where, as a White House correspondent, he won three straight Merriman Smith Memorial awards for broadcast journalism, and then to CNN, where he has continued to amass prizes for his coverage. He’s authored three nonfiction books—Body Slam: The Jesse Ventura Story (1999); Down and Dirty: The Plot to Steal the Presidency (2001), about the aftermath of the 2000 election; and The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor (2012). He also serves as contributing editor to DAM.

We caught up with Tapper June 7, the decisive day of the California and New Jersey primaries, when Hillary Clinton would celebrate clinching the Democratic presidential nomination. He was in the middle of working a double shift. After interviewing World War II veterans in the morning, he was preparing to anchor an unusual all-politics version of The Lead at 4 p.m. before settling in for election coverage that would last till 3 a.m. “I think it will be an historic night—for the first woman to declare that she has earned enough delegates to be a major party nominee. That’s pretty huge,” he says.

Among other subjects, we discussed this unprecedented election year, Tapper’s time at Dartmouth, his surprising friendship with Monica Lewinsky, why he left ABC and his newfound admiration for America’s military.

Do you feel a tension between your personality and political inclinations and trying to be an impartial anchor and interviewer and debate moderator?

I would say my life experience in the 1990s convinced me that neither party has all the answers. Even when I was at Salon in 1999 and 2000, I was pretty tough on both Gore and Bush. I have spent a lot of time devoted to being as agnostic as possible, in terms of not coming to the table with an ideology. I don’t subscribe to an ideology because I don’t think that any of them are correct. So it’s easier for me just to ask questions.

“I would say my life experience in the 1990s convinced me that neither party has all the answers.”

You must have a value system.

I have a value system. I’m against discrimination. I’m in favor of truth. I’m in favor of transparency. I’m in favor of honesty. I’m in favor of kindness. But that value system is not necessarily reflected by either party or any politician. I can’t look at anybody running for president today, or anybody who is president or has been in the last 20 years, and say, “This person upholds the values that I hold dear.” I don’t think President Obama has been transparent. I think he has been misleading on a number of things. Same thing with President Bush.

Therefore, it’s much easier for me to not belong to a team because I don’t like either of the teams in particular.

But that’s been an evolution?

To a degree, but I think it was kind of how I viewed the world even at Dartmouth. The comic strip I did in college [“Static Cling,” which appeared daily in The Dartmouth] made fun of everybody. It made fun of the administration. It made fun of fraternities. It made fun of protestors. It made fun of feminists. It made fun of the football team.

So the journalistic ideology of skepticism toward the world—that’s your natural inclination.

I think so. When I look back on my early days, when I was 22 or 23 and I was a Democrat, I was uncomfortable with people in the Democratic Party, even when I worked as a Democrat on Capitol Hill in 1993. Seeing it from that point of view doesn’t make you like it any more.

Being close to it feeds the skepticism.

It made me like them less. And, honestly, it was not difficult to see the Republican Revolution coming and, in many ways, deservedly so, because there were so many things that the Democrats were wrong about when it came to transparency and having laws applied to Congress that they passed for the rest of the nation.

I understand that you don’t vote anymore.

Yes. The year 2000 was the first election I voted as a reporter covering the national election. And I did not like how it made me feel as a correspondent in the field covering Bush and Gore because I felt like I was invested in one of them. And I didn’t like how that made me feel as somebody who a) didn’t particularly care for either of them, and b) was skeptical of both of them.

Obviously, this has been a very interesting election year. Can you describe it in just a few words?

Nerve-wracking. Unpredictable. Confounding. Intense.

What’s been most surprising to you?

There are a few things. One of them is that the Republican Party establishment and leaders have been so out of touch with their own voters. [Also] Donald Trump’s rise and his wiping of the floor with really, really impressive Republican presidential candidates such as Marco Rubio and John Kasich and Jeb Bush and all the others.

I think some of the journalistic failures have been surprising. Look, I understand that it’s difficult to fact check and push back on every single sentence that is questionable. I get that. But there’s a lot of stuff that has been allowed to let slide. I think that Hillary Clinton has been saying things about her private email server that the inspector general made clear he thought were completely false. With Donald Trump, whether it’s suggesting that Ted Cruz’s dad had something to do with the Kennedy assassination or bringing Vince Foster back into the discussion, there have been a number of things that are patently false that have been allowed to stand.

It seems like Trump’s technique is filibuster.

That’s everybody’s technique. But, yes, he bulldozes through.

He doesn’t stop talking. It’s very hard to get in to follow-up. I can see you looking a little frustrated at times.

He said something that was, as I said, the dictionary definition of racism. You say somebody can’t do a job because of their heritage, because of their race, that’s bigotry, period. It’s the definition of it. By the way, if he wants to criticize that judge [Gonzalo Curiel, who is presiding over a Trump University civil fraud case in California] for being a liberal, fine. That’s politics, that’s fair. But you know, this was just outright wrong. So I wanted to challenge him on the point. What ended up being interesting about it was the fact that he kept on pushing back and I quietly but persistently kept on trying to make the point and get to the big question, which was, if that’s your argument, isn’t that the definition of racist? And finally I did get there. I didn’t give up.

He didn’t agree that it was racist.

It didn’t matter at the end of the day whether or not he agreed with it. Sometimes the question is more important than the answer.

“I think sometimes the media gets blamed for the behavior of politicians.”

It’s been said that Trump somehow changed the rules of the game.

I think he’s changed the rules of the game in the sense that he has been bringing the art of personal insult and the negative branding and attacking the press to new levels that we haven’t seen in a long, long time. You probably have to go back to [former U.S. Vice President] Spiro Agnew to get a major politician who attacks the press as much as he does.

So far, it hasn’t cost him much.

Well, that remains to be seen. He was certainly able to win the Republican presidential nomination, but I think the question exists, has he said enough things along the path to nomination that will prevent him from winning the general election? I don’t know the answer to that. I think it’s possible, but it’s also possible that in the sense that he’s changed all the rules, maybe he will be able to redraw the electoral map.

It just seems so unlikely.

So does his winning the nomination.

Nobody predicted that.

That’s not entirely true. Last summer and fall I said to people here that I didn’t see a way that anybody could stop him from getting the nomination, once he shot to the top of the polls in July and initially nobody went after him. And then when people started responding, they were just awful. It became clear to me that he was onto something.

So the candidates failed to stop him. It’s not the media’s role to stop candidates, but is there anything that you would have done differently?

I look back at my Trump coverage and I don’t have many regrets. I think from the very beginning I’ve been asking him tough questions.

Certainly your February interview, when Trump refused to disavow support from white supremacist David Duke, was a big moment.

I think there are a number of interviews. Some of them didn’t get as much attention at the time. I did a 20-minute [interview] after he came out with his Muslim ban.

Are you getting better at interrupting the monologue?

I’ve gotten to know Trump and Clinton better and figured out how to interview them better. One of the things I’ve learned about interviewing is, in general, the tougher the question, the more calm the delivery should be. That’s something I initially learned when I was a White House correspondent for ABC News.

How does that help?

Because if it’s a histrionic or passionate delivery, then that can distract from the question. Whereas if the question is about white supremacists or an email server or racism or questionable contributions to the Clinton Foundation or whatever, you want the answer to be what’s important.

You’ve been referred to as brash. Is that something you’re trying to move away from?

I think, first of all, I’m older and more mature.

Some good things come with age.

Absolutely, but I was doing a different job back when I was called that, when I was a young dot-com reporter [with Salon] on my own on the road, trying to ask questions alongside people from The New York Times and Newsweek and Time. Being brash was a helpful part of the job. Now I’m almost 20 years older and I’m an anchor and I don’t need to do that.

You moderated three GOP presidential debates and a forum with the Democratic candidates this cycle. Do you think the debates serve the public well or could the format be tweaked to make them better?

I would say that it is near impossible to do an 11-person debate. I think in general the debates did serve the public a great deal, especially when fewer candidates were on the stage. People’s positions and leadership styles were revealed to the Republican electorate. And I think sometimes the media gets blamed for the behavior of politicians.

Or the behavior of voters.

When people look at the Republican candidate and the Democratic candidate and they say, “Oh, this choice. How did we get her? How did we get him?” the media gets blamed. The party gets blamed. No one ever blames the people who actually picked them.

The truth of the matter is I think that the American people—those who support Bernie Sanders and those who support Donald Trump and even a bunch of those who supported Ted Cruz—are not wrong if they feel Washington is broken. This is a city in which political contributions dictate the influence you have in Congress and the bills you can get passed.

We’ve had close to two dozen candidates from just the two major parties in the presidential race. Are there former candidates you particularly miss?

Personally I got along well with Chris Christie and Marco Rubio.

They’re big personalities.

They’re big personalities, but I’m from Philly, so Christie comes from a mold that I know well. Like [former Philadelphia mayor and Pennsylvania governor] Ed Rendell, the big, brash, urban guy. And I’ve known him for a long time. Then Marco Rubio and I are roughly the same age and [have] roughly the same interests. Rand Paul I missed when he dropped out just because otherwise there were very few people giving voice to that kind of libertarian, conservative position.

Who do you think was most adept at dealing with the press?

You’d have to say Trump in terms of the way he played many of my colleagues like a fiddle. He is very good at driving a narrative, and he’s also good at intimidating people. It is very, very tough to challenge these people. Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump are intimidating. They’re charismatic. They’re tough. These are two of the toughest people in the world. I know firsthand it is difficult, it is emotionally taxing.

Do you feel stressed when you have to interview one of them?

Of course. It’s very stressful. I have to steel myself. I have to prepare intellectually, but I also have to prepare emotionally. It’s not easy to do. If it were easy to do, then the times that I’ve done it wouldn’t get noticed.

What are Clinton’s media strengths and weaknesses?

Compared to Bernie Sanders, she’s more polished, more predictable. I think her predictability is a weakness. I don’t know that just retreating to talking points is something that voters or viewers find compelling at all.

How has TV news changed in the time that you’ve been involved?

I started full time in TV news in 2003. Since then I think network news coverage in general has really gone downhill: much less international coverage, much less political coverage. When I started at ABC News in 2003, it was Charlie Gibson and Diane Sawyer in the morning, Peter Jennings in the evening and Ted Koppel at night: icons.

In terms of cable, which is a different beast in many ways, I think that our two competitors [MSNBC and Fox News] have pursued ideological paths as business models, and that’s fine. But I think that leaves CNN as the only cable news network that is just trying to call balls and strikes and be down the middle.

How is the culture of CNN different from the culture of ABC?

First of all, cable news is 24 hours a day, seven days a week. And ABC news is—if you add up Good Morning America, World News and Nightline—three hours. Second, it’s hard to argue that all two hours of Good Morning America is news. So it’s less than that. So it’s not enough airtime versus too much airtime.

We have commercial imperatives, but we don’t have the same ones. So, for instance, during the New Hampshire primary we got enough interviews that [CNN president] Jeff Zucker said, “Well, why don’t we just do it without commercials?” And we did a full hour, no commercials. That would never happen at a network.

Could anything have kept you at ABC? I know you wanted to anchor This Week [ABC’s Sunday morning news program, for which Tapper served as an interim host]?

Yes. But if I had stayed at ABC I would not have moderated any presidential debates. I would not have been part of all the election night coverage that we’ve had because they don’t do it. I would not have had the moments with Donald Trump or Paul Ryan or Hillary Clinton or Marco Rubio—big, exciting news moments that changed the conversation for a day or two.

I would not be happy if I had stayed. I haven’t even talked about covering the Israel-Gaza war, going to France after the terrorist attacks, going to Boston for a month after the terrorist attack there. I wouldn’t have done any of that.

With your two shows—State of the Union and The Lead with Jake Tapper—you have the flexibility to be political junkie on Sunday and then just go to whatever the biggest story is during the week. And also do some pop culture.

Exactly. A friend from my childhood who works in Hollywood asked me what my dream job would be. The truth of the matter is I don’t know that I’m not doing it right now.

So you made the right choice?

I think so. I don’t look back.

But did you leave because you didn’t get the Sunday morning show?

I left because I wanted to be an anchor.

And CNN made the offer.

I didn’t see a path at ABC. I saw what Diane and Charlie and Ted and Peter did, and I wanted to do it. And I felt like I was ready to do it.

Let’s flash back. When you were young, you split your time between Queen Village in Philadelphia and the Philly suburbs?

I was born in Staten Island, and when I was 2 or 3 months old, we moved to Queen Village. My mom and dad divorced in 1977. My dad lives in the suburbs in Merion. My mom still lives in that house in Queen Village. My parents had joint custody of us, me and my brother. They are both big parts of my life.

My dad went to Dartmouth. He’s a ’61. I went up to Dartmouth for the first time for his 25th reunion and fell in love with it and wanted to go there. I’m about to take my kids up for my 25th reunion.

You had a Jewish education at Akiba Hebrew Academy. And you had this complicated family life. How do those factors play into who you are today?

I don’t know that the Jewish education plays into anything other than that it was a tradition of debate and discussion. And that probably had some influence. And I was the editor of the school paper when I was at Akiba.

In terms of my parents’ divorce, I’m sure at some point seeing things from two different people’s points of view might have played some sort of role, and trying to be fair to both sides. Probably the biggest lessons from my parents’ divorce were more personal ones that I hope I’ve learned for my marriage, but not necessarily for my profession.

You were a history major at Dartmouth, modified by visual studies.

I had to get special permission for history modified with visual studies, because at the time I wanted to be a political cartoonist. I wanted to be the next Garry Trudeau. After graduation I came up with a comic strip and I met with the head of the syndicate, but ultimately it just didn’t work out. I came close, but ultimately they passed.

What else was important to you at Dartmouth?

The comic strip was very important. And the criticism that came with it, too.

That helped you develop a tougher skin?

It’s never as tough as it should be, but yeah.

And were you in a frat?

I was in a fraternity [Alpha Chi Alpha] but I de-pledged.

Why?

Because the combination of alcohol and sexism and conformity made me uncomfortable and made me not like who I was in that setting. And it made me not like how people I normally appreciated behaved. So I quit, and I actually gave a speech about it during the Barge Oratorical Contest and won the speech contest senior year.

You had a ponytail in college, I understand.

It was the 1980s. There were a lot of unfortunate hairstyles going on back then.

In 1998 you achieved some national notoriety with a story [in Washington City Paper] on a date you had with Monica Lewinsky. How do you feel about it today?

I always tell people when they say anything about it: Read it and then tell me what you think.

You stand by that story.

I defended her. I suggested that people in Washington were too gleeful about the scandal, the fact that this young woman was being destroyed. Keep in mind it was within a week of the scandal breaking. And the White House was still denying it. They were putting out there that she was insane and she had made it all up.

You called it a B-minus date.

I wasn’t calling her B-minus. I was just saying the date was fine. It wasn’t like sparks flew and we fell in love. She appreciated the story. She reached out and we are friends now.

What did she say?

Thank you.

Even though you called her chubby?

If I could go back, I would take that out. I was in my 20s and a single guy and I would say not the most enlightened version of myself.

Overall, she liked it.

I’m still in touch with her today. She’s a very impressive woman. I think a lot of people would not have been able to survive what she went through.

You’ve managed since then to write three books.

The one I’m proudest of is The Outpost. That one was years in the making.

How did you find the time to conduct 225 interviews for it?

Every night, every weekend, every vacation day for a year and a half.

And you went to Afghanistan a couple times?

Once with President Obama, so it was in and out. A second time I went and flew in and was embedded with troops for about a week.

This was after the attack had taken place.

Yes. I heard about the story in the hospital after my wife had just given birth to our son, Jack. He was born October 2 [2009], and this happened October 3. Sometime after the attack I was holding him and listening to a report about this outpost in this impossible position: 400 insurgents attacking 50-plus Americans. Eight were killed and it was the bloodiest day for U.S. troops in Afghanistan that year. I never heard an explanation as to why that outpost was in that location. Then I just set out to find out. It ended up being this big book about this one combat outpost and [its] history.

Soldiers who had been there were really ecstatic about the book.

That’s the best part about it—how much the people who served there embraced it.

The book was very sympathetic to the soldiers on the ground and critical of the mission and the strategy, right?

I think that’s fair.

Had you thought much about the military before that?

My grandfather and his brother served in World War II. His brother was killed. But I never served. The truth is I had not thought much about it. Once I started writing the book I realized that this was a hole not just in my coverage but in my worldview. The whole experience was an awakening for me.

I remember one time I had come back from a meeting with two soldiers who are now friends of mine, Dave Roller and Alex Newsom. I’d had some beers with them and they told me about people from their deployment who had been killed. And I just came back and said to my wife, “I’ve just achieved nothing. I’ve sacrificed nothing. All I’ve done is pursue my own self-interests and tried to get ahead in the world for myself. And look at these guys—these are the guys who should get the attention.” And she said, “But you are here to tell their stories.” And it was a very profound moment.

You’re involved now in philanthropy for veterans?

I’m an ambassador for Homes for Our Troops, which builds mortgage-free specially designed homes for the most severely wounded troops from Iraq and Afghanistan. After I accepted an invitation to draw the comic strip Dilbert for a week from the cartoonist Scott Adams, we auctioned them off for Homes for Our Troops on eBay and we raised $10,000.

Let’s talk about your family. You met your wife, Jennifer Marie Brown, on the road.

I was in Des Moines covering the Iowa caucuses for Good Morning America. It was the day of the caucuses and all the big hitters flew in, so I knew I wasn’t going to go on. So my producer and I went out. When [John] Kerry won, we said, “Let’s go to the Kerry campaign headquarters, because that’s where the party will be.” And I walked into the Hotel Fort Des Moines and there was Jennifer.

At that party?

At the hotel bar. I saw her and I walked up to her and we went out the next day in D.C. and that was it.

So that was the A-plus date.

It was for me. It was worth a second date for her is all I can say.

You obviously adore your kids, but you work seven days a week.

I do. But we take trips.

Your wife isn’t working now?

She does some part-time work for a group called Upstream, which is working to make sure that birth control is available to all women.

What do you know now that you wish you’d known 20 years ago?

The tone thing that we talked about earlier. I think that I would have been more effective, that I would have been a better journalist. All of the stuff about covering veterans and being aware of veterans, I wish I had been aware of back then.

Do you have a hobby beyond…

My kids and this job? I write. I’ve been working on a political novel. I don’t know what will happen to it.

Julia M. Klein, a former political reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer and a contributing editor at Columbia Journalism Review, lives in Queen Village. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein.