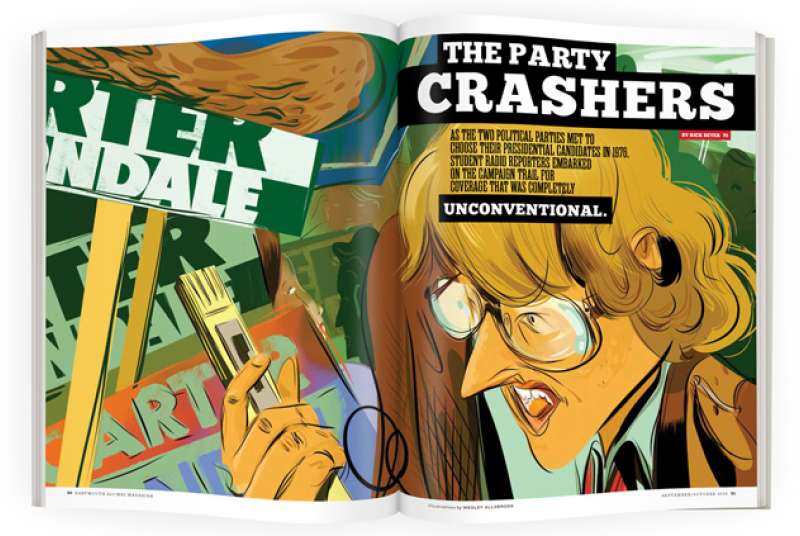

The Party Crashers

The shouting and tumult had faded away hours earlier. As NBC anchorman David Brinkley trudged wearily down the broken escalator at 2:30 a.m., the clanking sound of his heels on the metal treads echoed through the deserted lobby of Madison Square Garden. That’s when the kid caught up to him. Twenty years old, shaggy hair, aggressively unfashionable glasses. A reporter of some kind, with a cassette recorder slung over his shoulder and a microphone in his hand. The kid peppered the legendary journalist with questions about network coverage of the just-completed Democratic National Convention. Brinkley, famed for his acerbic put-downs, gamely answered until the kid pushed too far when he asked if the networks’ convention coverage wasn’t really more about showmanship than journalism.

That’s when Brinkley let him have it: “That is such a stupid remark, I won’t really respond to it. I don’t want to talk to you anymore.”

Forty years ago I was that wide-eyed kid. One of a handful of students from Dartmouth Broadcasting crazy enough to inveigle our way into the national political conventions to cover them for campus radio stations WDCR and WFRD. As I stood watching Brinkley walk away, I blurted a few words into my tape recorder. “He looks more exhausted than maybe a candidate himself. He was absolutely dead tired, eyes shut.” I paused for a moment, searching for the right words to capture the overwhelming experience of being at the convention.

“Shock! I can only express my feeling after this whole convention is…,” I paused, “shock. It’s not a real world!”

LISTEN: “Brinkley Interview,” Democratic Convention, July 16, 1976

“I caught up with NBC anchorman David Brinkley at about 2:30 AM on an escalator at Madison Square Garden. He was pretty testy, but listening now, my sympathies are all with him.”

It all began months earlier, on the night of February 24, 1976, when dozens of student reporters from Dartmouth Broadcasting fanned out to cover the first-in-the-nation New Hampshire primary. Jeffrey Sudikoff ’77 led the team that produced the ambitious primary-night coverage, which included computer projections, expert commentary from Dartmouth professors, and even live interview segments with notorious Manchester Union Leader publisher William Loeb. Thirty stations across New England were brave enough to carry the student-produced broadcast. “We had absolutely no doubt this was important stuff that we should be doing and that we absolutely knew how to do it, when in fact we didn’t know anything,” recalls Richard Mark ’77, then general manager of the radio stations, now an attorney in New York City. “But without the slightest trepidation we just went out there and did it.”

We exulted in covering campaign events, hobnobbing with candidates and the celebrity media that trailed them. But we weren’t always the political geniuses we imagined. Bob Baum ’77 was responsible for interviewing each of the candidates who came to Hanover that winter. “I had my picture taken with every one of them except Jimmy Carter, because I knew there was no chance he would get the nomination, so why bother,” he says.

Having witnessed the start of the presidential campaign, a few of us dreamed of seeing it through by attending the conventions. In a day before reality TV littered the cable channels, a political convention was the ultimate reality show, the greatest media event imaginable: All three major networks broadcasting hours of live, prime-time coverage from one huge room filled to bursting with thousands of politicians, reporters, spectators and hustlers. As journalists who wanted to prove ourselves, as political junkies with a taste for the action, as students of history eager to see history being made, we longed to be there. So we fast-talked our way into media credentials, persuaded our professors to let us skip class and hit the road.

First stop, New York, where the Democrats were planning a coronation party. Carter had astonished not just Baum but the entire Democratic Party establishment by roaring out of nowhere to win the nomination. The convention opened in Madison Square Garden on Monday, July 12, and we were there with our cassette recorders whirring. Our team of intrepid reporters numbered three: My future best man and business partner, Mark Tomizawa ’78, Baum and me. The morning of the first day construction sounds still rang through the arena. “We were fascinated by the gazillions of miles of wires,” Tomizawa remembers. “They were still hammering it together like a community theater project.”

Once the convention began, the action was out on the floor. Getting there required a floor pass, a laminated piece of cardboard that was our ticket past the growling mastiffs in cheap suits jealously guarding the access points. Floor passes were more valuable than gold, and harder to come by. We were credentialed as local radio reporters—not quite the lowest of the low, but close. We could get only an occasional 20-minute timed floor pass, and if we didn’t return it promptly we would risk having our credentials ripped off and being escorted to the door. Hitting the floor with a timed pass was like a spacewalk, where you balance your desire to stay out as long as you possibly can with the fact that your oxygen is ticking down second by second.

“Suddenly there was a large, powerful hand on my head that pushed me back really hard. I fell on my butt and looked up to see a Secret Service man.”

The floor was a carnival. Characters from every corner of America packed together at the pulsating center of American politics. Look, there’s Candice Bergen in a cat suit, shooting the event as a photographer. That old man is Averell Harriman, who negotiated with Stalin and Churchill. Over in the Illinois delegation, isn’t that Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley? One night I interviewed Daley about his favorite conventions. Would you be shocked to discover that Chicago 1968 did not make the list? Another evening I saw a youthful Tom Brokaw conducting a live interview and wormed my way up close to observe. (Close enough that my father, watching at home, saw me and snapped a picture of the TV screen.) Tomizawa was awed to see his hometown hero, Jesse Jackson. He went over with what he thought was a great bonding line: “Hi, I’m from Chicago, too.” He was crestfallen when Jackson gave him a withering look and walked away.

The chairman of the New Hampshire delegation was government professor Larry Radway. The night of Carter’s nomination he cooked up a caper to extend my stay on the floor. He slipped me his state chairman credential, which of course had full floor privileges. I hid it inside my jacket pocket, walked off the floor and turned in my timed floor pass as usual. Then, going to another entrance, I waltzed in showing Radway’s pass. They must have thought the New Hampshire delegation had an awfully boyish chairman! I furtively returned the pass to Radway and on this historic night I had the run of the floor—so long as nobody found me out.

Clever as that trick might have been, Baum came up with a much simpler expedient the last night of the convention. He boldly barreled through the security checkpoint and lost himself in the crowd. “I got a terrific spot on the floor for Jimmy Carter’s acceptance speech,” recalls Baum, now an environmental attorney in Washington, D.C. He showed off all of his rule-breaking skills that night. Later on he attended a wild press shindig thrown by NBC. “I was ordering gin and tonics until they ran out of tonic, and then it was just gin. I stole the NBC placard and ran out of the building, NBC staffers running after me. I was just getting into the cab and they took it back.” He chuckles at the memory. “Those news people are hardcore drinkers. They drank me under the table.”

The Democrats had barely dispersed before we began plotting how to get to the GOP convention being held a few weeks later in Kansas City, Missouri. The radio station didn’t have money to send us and none of us could afford the airfare. But I knew that President John Kemeny had both a discretionary fund and open office hours for students. In his spacious Parkhurst office I nervously pleaded our case, seeking the grand sum of $1,000 to purchase tickets to Kansas City.

Kemeny chain-smoked as he listened in silence. Then he responded in his soft-spoken, Hungarian-accented English. Was I aware that the Choates dorm cluster had a fund for guest speakers? Perhaps we should approach them for money and offer to hold a seminar there when we returned. Then he rattled off a second possible source of funding, a third, a fourth. “Tell them I suggested you contact them,” he said. Pause, long exhale. “Then come back to me and I will give you the rest.” We raised about half the money from the sources he suggested, and he supplied the balance, winning a permanent place in my heart. For the trip to Kansas City Tomizawa and I were joined by Kevin Koloff ’77, now an entertainment lawyer in Los Angeles, and Nancy Levin, a Smith College ’76 who was a Dartmouth exchange student—and whose parents in Kansas City were willing to house us.

The 1976 GOP convention holds the distinction of being the last contested convention in U.S. history. The campaigns of President Gerald Ford and challenger Ronald Reagan rolled into town after six months of hard-fought primaries and caucuses. The 100-degree heat in mid-August was punishing, but there was no time to relax. The two candidates were in a virtual dead heat for delegates. The Ford campaign, led by the president’s young chief of staff, Dick Cheney, held the slightest of leads. “You didn’t really know who was going to get the nomination at that point,” recalls Levin. The dwindling number of uncommitted delegates were showered with gifts and attention. “Better a mistress than a wife,” is how one of them playfully described it to Tomizawa.

“Even as wet-behind-the-ears kids we thought we had something to contribute to the nation’s political conversation.”

We brought one piece of state-of-the-art technology with us to Kansas City: a portable teleprinter with an acoustic coupler. Weighing 25 pounds, “it looked like a Smith-Corona typewriter case on steroids,” says Richard Mark, the GM. We used a telephone to dial into Dartmouth Time Sharing, then carefully placed the handset in a cradle, making sure the mouthpiece and earpiece fit just right. Then it transmitted data over the phone line in a series of whistles and chirps. Blazing speed: A single page of copy took only 90 seconds! “I vividly remember the modem and how hi-tech it was,” recalls Koloff. “I remember guys from TV networks coming by to say, ‘What the hell is that?’ ”

Mainly, though, we relied on cassette recorders. I borrowed one from future NFL kicker Nick Lowery ’78 because the radio station didn’t have enough to spare. Lowery’s machine was a little worse for wear when I returned it. The only sound it made was a grinding death rattle. This displeased him mightily, and he showed up at my dorm room one night with a couple of his football buddies. To avoid the potential of bodily harm, I swapped his recorder for one that still worked. “I remember you coming home with some broken electronics,” recalls Jordan Roderick ’78, chief engineer of the station and now a retired telecommunications executive. But he never knew about my secret swap.

With President Ford in attendance, the Republican National Convention was swarming with Secret Service agents. Koloff spotted the president’s son, Jack Ford, behind a rope barrier and stepped over to get the interview. “Suddenly there was a large, powerful hand on my head that pushed me back really hard,” says Koloff. “I fell on my butt and looked up to see a Secret Service man. The most humiliating thing is how easy they make it look. I was in prime shape, but he had no need to call for backup.”

LISTEN: “Kemper Frenzy,” Republican Convention, August 17, 1976

“This is an ‘explainer’ for the afternoon news on WDCR about the fight-to-come at the GOP convention over the critically important Resolution 16C. I used my very serious grown-up radio voice, and also managed to throw in some history for context.”

The outcome of the convention came down to a frenzied floor fight over the innocuously titled Resolution 16C. (It called for both candidates to choose a running mate before the first ballot.) During the maneuvering, Koloff covered a press conference by Reagan campaign manager John Sears, famously allergic to giving a straight answer. Koloff memorably described Sears in a radio report as being “slippery as a greased watermelon at the bottom of the swimming pool.” The night of the vote on 16C, Kemper Arena (which resembled a giant plumbing fixture) was rocked with waves of emotion as events unfolded. I saw Vice President Nelson Rockefeller ’30 stride up the aisle and rip a sign away from a Reagan delegate and tear it apart. Someone ripped out a floor phone that belonged to the Reagan forces, and Rocky held it aloft while Ford delegates roared. As I wrote in my report that aired on WDCR the next morning, “Politics translated into passion on the floor of the convention last night.” Ford won—just barely. Reagan would have to wait four more years for his turn.

The outcome of the convention came down to a frenzied floor fight over the innocuously titled Resolution 16C. (It called for both candidates to choose a running mate before the first ballot.) During the maneuvering, Koloff covered a press conference by Reagan campaign manager John Sears, famously allergic to giving a straight answer. Koloff memorably described Sears in a radio report as being “slippery as a greased watermelon at the bottom of the swimming pool.” The night of the vote on 16C, Kemper Arena (which resembled a giant plumbing fixture) was rocked with waves of emotion as events unfolded. I saw Vice President Nelson Rockefeller ’30 stride up the aisle and rip a sign away from a Reagan delegate and tear it apart. Someone ripped out a floor phone that belonged to the Reagan forces, and Rocky held it aloft while Ford delegates roared. As I wrote in my report that aired on WDCR the next morning, “Politics translated into passion on the floor of the convention last night.” Ford won—just barely. Reagan would have to wait four more years for his turn.

LISTEN: “Resolution 16C,” Republican Convention, August 17, 1976

“This WDCR report was filed moments after stepping off the floor of the convention during the raucous fight over Resolution 16C. I was caught up in the moment, thrilled to be present while history was being made.”

After securing the nomination, Ford went to Reagan’s hotel to make peace. Midnight was long past and both were clearly exhausted, but they dutifully emerged from their meeting and took questions from the press. Koloff came up with a sneaky strategy for getting the president’s attention. He wadded up a piece of paper and threw it at the technician pointing a shotgun mic toward the reporters. The technician turned to discover the source of the paper projectile and his mic swung toward Koloff. “President Ford saw the mic pointing at me and said ‘You, next question,’ ” recalls Koloff, who made the most of his opportunity. He asked if Ford had made up his mind about a running mate yet. “I have not,” the president succinctly answered.

We were riding high, intoxicated by our proximity to all this political theater. The following day, however, Ford’s choice of Sen. Bob Dole as his running mate would lead to our lowest moment. “We were young and a little bit reckless and full of ourselves,” says Koloff, by way of explanation. “Very late that night I got punchy and stupid and sleep-deprived and recorded a story that purported to be a profile of Dole. In reality, it was just a series of tasteless bad jokes about his arm.” Dole has little use of his right arm, injured during World War II. He is a legitimate American hero, and to say our jokes were sophomoric would be exceedingly kind. “His favorite book was A Farewell to Arms. His hobby was taking his rowboat out for a spin.” It seemed hysterically funny to us at the time.

It was less funny when I accidentally included this report on a list of stories that we sent back to WDCR early the following morning that in turn were submitted to the AP Radio feed that went out to radio stations across New Hampshire and Vermont, some of which played the story without listening to it first. My memory is mercifully blank about the repercussions that followed. Suffice it to say it was very embarrassing for us all. We so wanted to think of ourselves as serious reporters, but perhaps we weren’t quite out of the bush leagues yet.

Thinking back to my truncated conversation with David Brinkley, I recall his response when I challenged him on why NBC was devoting so many resources to a Democratic convention where so little was happening. “I think we have a duty to do it,” he said. And that’s what we believed too. We had a duty to do it, or at least to try. Yes, we thirsted for adventure and gawked at celebrities. Yes, we occasionally blundered. But even as wet-behind-the-ears kids we thought we had something to contribute to the nation’s political conversation. “I thought that was a big deal, to be filing stories about something of national importance,” recalls Levin, now a docent at the Phoenix Art Museum. We all did. While our coverage certainly contained its share of showmanship, I believe there was some worthwhile journalism there as well.

Rick Beyer is an author and documentary filmmaker. He lives in Lexington, Massachusetts.