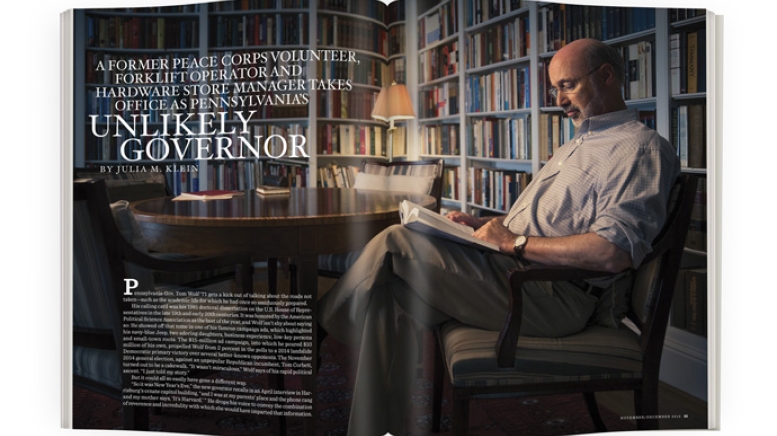

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf ’71 gets a kick out of talking about the roads not taken—such as the academic life for which he had once so assiduously prepared.

His calling card was his 1981 doctoral dissertation on the U.S. House of Representatives in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was honored by the American Political Science Association as the best of the year, and Wolf isn’t shy about saying so: He showed off that tome in one of his famous campaign ads, which highlighted his navy-blue Jeep, two adoring daughters, business experience, low-key persona and small-town roots. The $15-million ad campaign, into which he poured $10 million of his own, propelled Wolf from 2 percent in the polls to a 2014 landslide Democratic primary victory over several better-known opponents. The November 2014 general election, against an unpopular Republican incumbent, Tom Corbett, turned out to be a cakewalk. “It wasn’t miraculous,” Wolf says of his rapid political ascent. “I just told my story.”

But it could all so easily have gone a different way.

“So it was New Year’s Eve,” the new governor recalls in an April interview in Harrisburg’s ornate capitol building, “and I was at my parents’ place and the phone rang and my mother says, ‘It’s Harvard.’ ” He drops his voice to convey the combination of reverence and incredulity with which she would have imparted that information.

“So I pick up the phone,” Wolf continues, “[and] this professor says, ‘We’ve heard a lot of good things about your dissertation. We’d like you to come up and interview for a tenure-track job.’

“I said, ‘Thank you, but I’m not in a position to accept.’

“So he says, ‘Well, Harvard’s a good school.’ ” (It’s hard to imagine the professor actually saying that, but never mind—Wolf is clearly savoring the anecdote.)

“I said, ‘I know, but I’ve made other commitments.’

“So he says, ‘Where will you be teaching?’

“I said, ‘I’m not going to be teaching.’

“He said, ‘Doing research then?’

“I said, ‘No, I’m not doing research.’

“He said, ‘What are you going to do?’

“I said, ‘I’m going to be managing a True Value hardware store in Manchester, Pennsylvania.’ ”

It’s a great story, and a characteristic one, too, in its blend of pride and wry self-deprecation: One can imagine both the Harvard professor’s bafflement and Wolf’s own quirky satisfaction in dashing expectations.

There was method to the apparent madness, even if Wolf (who, with his beard and wire-rims, resembles a professor) hadn’t yet envisioned a political career. The hardware store was owned at the time by the Wolf Organization, his family’s building-products distributorship, and managing it was part of his apprenticeship. So, too, was an earlier, even more unlikely stint as a forklift operator, later ballyhooed in those same campaign ads.

In 1986 Wolf would partner with two cousins and buy the company from the older generation, as per family tradition. (“They didn’t actually understand the meaning of the word ‘inheritance,’ ” he quips.) Twenty years later he would sell all but 11 percent of his interest in the company for about $20 million. Pennsylvania Gov. Edward G. Rendell, whose campaign he had supported generously, would name him state secretary of revenue, and Wolf would start planning a gubernatorial run.

Despite his unassuming air, Wolf is both “confident in his own judgment and able to establish rapport with an opponent.”

Wolf says that managing that hardware store is the hardest job he’s ever had. Until, one is tempted to suggest, this current gig. Wolf, who turns 67 in November, said in April that he was having “more fun than anybody should” as governor. In mid-August, still ensnared in thorny, sometimes acrimonious negotiations with Republican legislators over a state budget impasse, he insisted that his enjoyment of the job hadn’t abated. “It’s still true,” he says. “I’m really having a ball.”

By then Wolf had slammed the GOP budget as “a sham,” “a disgrace” and “an insult” and had bemoaned the “continued intransigence” of Pennsylvania House Speaker Mike Turzai, a Republican. Turzai had called Wolf’s criticism “petty and childish.” After a deadlocked summer, there were signs that both sides were actually grappling with the issues, from increased public education funding (Wolf’s priority) to pension reform and the restructuring of the state’s antiquated liquor monopoly (both high on the GOP wish list).

In mid-September Wolf tried to remove those stumbling blocks with “historic” compromise proposals—then held an angry press conference denouncing GOP negotiators for giving him nothing in return. “We have wasted three months,” he said. “This is beyond pathetic.…This is ridiculous.” On September 24 Jennifer Kocher, a spokeswoman for Senate Majority Leader Jake Corman, a Republican, predicted that the two sides were “weeks away from any type of agreement.”

Christopher Borick, professor of political science and director of the Muhlenberg College Institute of Public Opinion, says the governor has performed “fairly admirably” and “shown that he’s interested in compromise.” He adds: “I think he appears at times to be a little frustrated with the nature of the process.”

“Frustration is part of any job,” Wolf says philosophically. “If you want to be a spectator, that’s how you avoid feeling frustration. But if you want to do something in any field, you’re going to feel frustration sometimes.”

“If he has made a mistake,” says Charles Gerow, a Pennsylvania Republican media strategist, “it was in believing that the voters gave him some sort of mandate last fall rather than that he beat a man who was politically unpopular at the time—and failing to understand that the voters did give a mandate to the general assembly all across Pennsylvania in record numbers.”

The GOP handily controls both houses of the general assembly, making Wolf’s administration a case study in the perils of divided government in an era of extreme political polarization. In Illinois Bruce Rauner ’78 (see “Meanwhile, In Illinois”) faces comparable obstacles as a freshman Republican governor battling an overwhelmingly Democratic state legislature. There is another parallel: Both men have been highly successful businessmen but came to office as relative political neophytes, in situations that would test even the most practiced politicians.

Confronting each state are economic problems familiar across the country: a structural deficit, a wobbling and expensive public pension system, a burdensome property tax structure, cities and school districts perennially strapped for funds. In Pennsylvania throw into the mix an unpopular state liquor monopoly, a byproduct of Prohibition that is also a source of state jobs and revenues. Republicans support privatization; the governor’s latest proposal involves leasing the system to a private manager, while making liquor easier to buy and protecting state jobs.

As in nearly every state, and in contrast to the federal government, Pennsylvania and Illinois are legally required to pass a balanced annual budget. As of late September the two were the only states in the country that had not yet managed that feat. To some extent that is not surprising: Reaching agreement requires traversing the chasm, at once predictable and seemingly impassible, between the Republican reluctance to increase taxes and the Democratic focus on providing for social needs.

Wolf’s $33.8-billion budget, unveiled in March, included $1 billion in new money for education, with the greatest boosts going to needy school districts such as Philadelphia. It also dramatically reconfigured the state’s tax structure, calling for lower corporate and local property taxes, higher sales and income taxes, and a 5-percent severance tax on the state’s thriving, if controversial, natural-gas industry. (Anti-fracking activists picket Wolf regularly.) Newspaper headlines called the plan “bold.” Republican legislators signaled their opposition. “He did, by his own admission, bite off an awful lot,” says Gerow. “Whether or not he can chew it is another question altogether.”

Wolf made clear early on that he was prepared to miss the June 30 deadline. On deadline day the governor issued a rare full veto, the state’s first in nearly 40 years, of a $30.2-billion Republican budget devoid of tax hikes, saying it relied on “smoke and mirrors” and included insufficient education funding. Gerow describes the full veto—rather than a line-item veto approach—as “a Pyrrhic victory at best [that] cost [Wolf] the high moral ground.” The biggest surprise, he says, has been just how “stubborn and recalcitrant” the new governor has turned out to be. “He’s doubled down every time there’s been a choke point in negotiations [and ] has dug in his heels at every turn,” the Republican strategist says.

The sprawling Wolf homestead—a white frame house with black shutters, a colonnaded portico overlooking a railroad track and a lawn bursting with daffodils—is surely the most elegant residence in Mount Wolf (population 1,393).

The borough was founded, and the house built, by Wolf’s great-great-grandfather, George H. Wolf. The future governor grew up here, in heavily Republican York County, and later bought his childhood home from his parents, who now live nearby. “It’s an old farmhouse,” Wolf says, “but a town grew up around it. It’s surrounded by an old lumberyard, a furniture factory and a box factory.”

The house is filled with books and family portraits. A detached structure next to it has been converted into an art studio for Wolf’s wife, Frances, whose often-surrealistic paintings have been widely exhibited. The celebrated Jeep sits out front, and a state trooper keeps a wary eye on the property. Instead of moving into the governor’s mansion, about half an hour away, Wolf—who donates his government salary to the United Way—sleeps here most nights and commutes to Harrisburg. He and his wife also own an apartment in Philadelphia, where they can be spotted enjoying ice cream on a park bench.

Mary Toomey, a retired music teacher in Mount Wolf, has known the governor since he was a child. As a 10-year-old he sang his lone solo in her church choir “very well,” she says—and at a campaign kickoff party she hosted he joked about not having been invited to solo again.

At 86, Toomey, who appeared in a campaign ad, is an unabashed Tom-and-Frances enthusiast whose home is filled with Wolf photographs, clippings and campaign and inaugural memorabilia. She recalls his early compassion for the underdog: “When he played with these kids in Mount Wolf and there was one kid standing off to the side who was not involved in whatever the game was, he’d walk over to them and he’d say, ‘Aren’t you going to help us? We need you.’ He wanted to get everyone involved.” After Wolf became governor, Toomey called him one evening about an absent neighbor’s barking dog. Wolf volunteered to take the animal in for the night.

Wolf attended the Hill School, a private boarding school in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, before matriculating at Dartmouth. He whizzed through college, spending, he says, only two football seasons there. He has vicariously enjoyed the more leisurely Dartmouth careers of his two daughters, Sarah ’04 and Kate ’06, he says.

Thanks to Advanced Placement credits, Wolf says he entered Dartmouth with the equivalent of sophomore standing. He participated in the Navy’s ROTC program but left school after freshman year to join the Peace Corps. “I was looking for something significant to do even when I was 19 years old,” Wolf says. His Peace Corps stint, more than two years in rural India, immersed him deeply in the agriculture of rice production.

On his return, he lived off campus, took summer school courses and majored in government. “I think what Dartmouth gave me was the same thing the Peace Corps gave me—a sense of efficacy, that you do things, you don’t sit around and wait for someone else to do things for you,” he says.

Through the 1972 George McGovern presidential campaign, Wolf got to know Kate Stith ’73 and her husband, Jeffrey L. Pressman, a government professor at the College. “We worked in the trenches together,” says Stith, a former Dartmouth trustee and the Lafayette S. Foster Professor of Law at Yale Law School. Pressman became Wolf’s mentor at Dartmouth and then at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where Wolf wrote his doctoral dissertation.

David Shribman ’76, executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and also a former Dartmouth trustee, says that Pressman exerted an unusual intellectual allure. “Like so many of our era and outlook, Gov. Wolf as a young man was drawn into the magical circle of Jeffrey Pressman,” recalls Shribman, who also studied under him.

That circle was broken when Pressman, just 33, died by suicide. Stith says that he had been depressed and had a family history of suicide. (Both Dartmouth and MIT have since created prizes in Pressman’s honor.)

Wolf, who had been Pressman’s teaching assistant at MIT, took over his mentor’s classes. “Jeff thought the world of him,” Stith recalls. Wolf spoke at the memorial service and stayed close to Stith; he later named one of his daughters for her. When Stith moved to Washington, D.C., for a job, she says, he “told me there was no need to hire a moving company; he’d take care of it. A few days later he and some friends showed up with a U-Haul truck.

“He always reminded me a little bit of Tom Sawyer—friendly, with an easy smile, easygoing,” she says. “I’ve never seen him lose his temper,” an observation seconded by others. (Wolf says that he has been known to give people “the hairy eyeball” when upset.)

Nelson Kasfir, an emeritus professor of government at Dartmouth, met Wolf in 1974 during a sabbatical at the University of London, where Wolf was earning his master’s. “He had this quality of being self-deprecating—an ‘aw, shucks’ kind of personality,” Kasfir recalls—so much so that Frances, who also met Wolf at the University of London, told an interviewer that she hadn’t at first realized he was proposing marriage.

Despite his unassuming air, Wolf is both “confident in his own judgment and able to establish rapport with an opponent,” says Kasfir. “He wouldn’t be stiff and he wouldn’t be off-putting—I think that’s a strength of his.”

Wolf is not a charismatic public speaker, a deficiency he is quick to note. But one-on-one he can indeed be charming, and that quality is on display during his legislative drop-ins, an unconventional practice he inaugurated soon after taking office.

At periodic intervals Wolf strides around the capitol building, popping in unannounced on selected legislators for a few minutes of casual conversation. The contrast with his Republican predecessor, Corbett, considered remote even by members of his own party, could not be more striking. Wolf also has aimed for more public accessibility, crisscrossing the state to build support for his proposals and holding “town halls” on Twitter and Facebook.

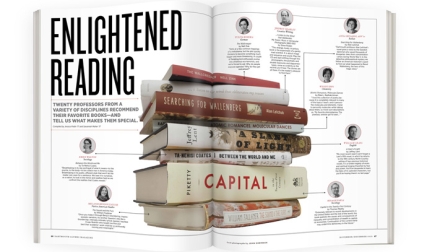

On the day of my visit the governor targeted several Republicans for impromptu schmoozing on subjects that included the political philosophy of John Locke, accountability in education, Seamus Heaney’s translation of the Old English epic Beowulf, Wilt Chamberlain’s storied basketball career at Philadelphia’s Overbrook High School and Robert Caro’s Pulitzer Prize-winning study of New York city planner Robert Moses, The Power Broker.

“In American democracy we’re all basically disciples of Locke. So the question really is what level of constraints do you put on overall behavior so we can optimize our individual freedom?”

“It’s unheard of, from my understanding,” says freshman Rep. Aaron Kaufer of the governor’s frequent visits to his office. “I give him a lot of credit.”

Wolf describes Kaufer as a “thoughtful Republican” and “a John Locke scholar.” Kaufer duly shows off his first edition of John Locke’s complete works, printed in 1714 and “bought as a present for myself after the election.”

“He’s actually a John Locke practitioner,” Wolf adds.

“I try to,” says Kaufer. “Free contract is actually the big thing to me—how democracy is supposed to be implemented in today’s environment.”

“It actually is a philosophical conversation between Republicans and Democrats,” says Wolf, launching into an enthusiastic, professorial explanation of the state of nature and the social contract. “In American democracy we’re all basically disciples of Locke. So the question really is what level of constraints do you put on overall behavior so we can optimize our individual freedom?”

His aides have to drag him away to the next meeting.

In August I asked Wolf whether all those drop-ins had had any political value. “I wasn’t trying to bamboozle anybody by getting to know them,” he responds. “I was trying to say that when we disagree, I want you to have a face that you can attach to the person you’re disagreeing with, and I want a face attached to the person I’m disagreeing with. So I wasn’t trying to change anybody’s mind.” Given the persistent ideological divide, he may not have. But it is true that informal meetings are a Wolf signature. Dave Confer, general counsel at WOLF (whose corporate parent is the Wolf Organization), says that his former boss used to visit the company’s lumberyards and warehouses to chat with workers about their concerns. “He had a very common touch,” Confer recalls. “At his core Tom really never thought that he was better than anyone else.”

Confer, who also has served as chairman and secretary of the company, praises Wolf as “visionary” and “rock solid in his integrity”—someone who “would tell you first and foremost you ought to do the right thing.”

In his initial two-decade stint as CEO and president Wolf expanded the business—from annual sales of $70 million in five states to $385 million in 13 states, according to his campaign biography.

He also immersed himself in philanthropic and civic enterprises, as he had always intended. “I remember walking through Copley Square in Boston, where the Boston Public Library was, with my wife,” Wolf says, explaining why he decided to forsake academia and return home. “And I said, ‘You know, if I really write a lot of books and articles and do a good job at MIT, maybe someday I can be on the board of the Boston Public Library.’ And then I said, ‘Wait a minute—if I go back to York, I can probably be the chair of the local public library within a couple of months.’ ”

He did far more. He ticks off the list: “I was chairman of the chamber of commerce, the United Way, the York County Community Foundation, the York College board of trustees, the York-Lancaster Heritage Region, WTIF—the PBS station,” not to mention president of a group called Better York.

In 2006 Wolf engineered the sale of the Wolf Organization to Boston leveraged-buyout firm Weston Presidio Fund V and a handful of employees—a prelude, he says, to his retirement. Around that time, as he tells it, Gov. Rendell “came to my house and said, ‘Would you like to do something in my administration?’ ’’ At first, Wolf says, he demurred. Then, after a couple of days of vacation, “I realized I wasn’t ready for retirement, so I came back and said, ‘What do you have in mind?’ ” (Rendell told Philadelphia magazine that Wolf had approached him first.)

In 2008 Wolf resigned as revenue secretary and picked a campaign team. He was planning to make his gubernatorial candidacy official immediately following President Barack Obama’s 2009 inaugural festivities. Wolf was still in Washington, D.C., when, he says, “I got a call saying the company was tanking and the bank was about to pull the plug.”

Confer, who organized that fateful conference call, says that the housing recession, not failed leadership or debt from the buyout deal, was to blame. He wasn’t expecting rescue, he says, but felt an obligation to inform Wolf, whose minority stake in the company was in a blind trust.

Wolf, in turn, felt his choice was clear: He abandoned his electoral hopes—he thought for good—in favor of trying to save the company. “I grew up with those folks,” he says. “That’s what you do. I think anybody would have done that.”

It was a risky decision, financially as well as politically. “Everything I’d taken out I put back in,” Wolf says, and he convinced his two former partners and even the buyout firm to pony up additional funds. Confer says that the management team also contributed.

In another dramatic move, Wolf says he decided around 2010 “to change the business model,” from distributing other people’s products to manufacturing WOLF-branded cabinetry and other building supplies. Confer says he was enthusiastic, but “a lot of people were not on board with this, including very senior management people in the company.”

And the transition wasn’t easy. “I don’t ever want to go through 2011 again in my life,” Wolf says. “But by the end of the year it was working, and by 2012 we had turned the corner and by the time I left in 2013 things were going very well,” so much so that WOLF now bills itself as the country’s largest manufacturer of kitchen and bathroom cabinets.

That turnaround became a linchpin of Wolf’s 2014 campaign, an essential credential when he decided, once again, to stage a seemingly quixotic run for governor.

In June another twist in the saga finally ended the company’s history of family ownership: Quad-C, a Charlottesville, Virginia, investment group, acquired control of the Wolf Organization for an undisclosed sum. Wolf, whose assets had once again been placed in a blind trust, was not involved in the deal.

Across from the Kensington Health Sciences Academy, an L-shaped building of stone and aqua tile, sits a massive fenced lot garlanded with refuse. In this blighted row-house neighborhood, in one of the country’s poorest congressional districts, flowering fruit trees clash incongruously with trash-strewn pavements. Traverse a few labyrinthine streets toward the highway and the shimmering postmodernist skyscrapers of Center City Philadelphia loom into view—like Oz suddenly visible from Kansas.

This specialized high school—which partners with community organizations, offers technical training in medical and dental fields and encourages college aspirations—is trying to transcend its surroundings. “What we’ve decided to do is simply raise the bar,” says principal James Williams. “We eliminate excuses and we work twice as hard.” The school’s corridors and classrooms are immaculate and orderly. Students wear uniforms: gray shirts with the school logo and black pants or skirts.

On this gloomy, drizzly April morning Wolf arrives in his own uniform of navy pinstripe suit and navy-and-white polka-dot tie. The stop is part of his ongoing “Schools that Teach” tour, his continued push for education investment. On hand are Philadelphia school superintendent William R. Hite Jr., tall and affable even as his district remains in perpetual crisis and cutback mode, and Mayor Michael Nutter, fuming at the lack of support for his proposed property-tax hike for the city. “You can’t say that you’re for kids, but not for paying for their education—that is bogus,” Nutter tells reporters, while praising the governor for seeking $159 million in additional aid for Philadelphia schools.

Beside the mayor, Wolf is a decidedly cool presence, a master of the soft sell. To a class discussing the Orphan Train, he touts the value of reading. And when Angela Iovine, an English teacher, explains that students writing essays are taught that they must support their arguments, he flashes his trademark wry humor.

“What?” quips the governor. “Not in politics.”

As of late September Wolf is still fighting hard for his priorities, using the state’s recent credit downgrades as ammunition. Although he says he is trying to minimize disruption, he notes that county human services agencies and nonprofits are feeling the pinch of delayed state funding. He has nevertheless promised to veto the Republicans’ “stopgap” funding measures—which he calls “a poke in the eye” and “hypocrisy”—until an agreement appears within reach.

“There is some temporary inconvenience,” he says. “If I were to cave, there’ll be some very long-term inconvenience.” The question, as he frames it, is, “Are you willing to tough it out and have a little bit of a fight in the hopes of getting a better Pennsylvania in the long run?” Showing a glint of steel, he is settling in for a siege.

Julia M. Klein, a contributing editor at Columbia Journalism Review, was formerly a political reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer. Her work has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Washington Post and Mother Jones.