Salad Days

Everyone in San Francisco has a Perry’s story. Such as: “I went there with the man who is now my husband—our disastrous first date. He still reminds me of the things I said!”

This quintessential bistro-bar with its blue-check tablecloths and small menu of American-French classics opened in 1969 in Cow Hollow, between two of the city’s most picturesque neighborhoods, the Marina and Pacific Heights. “It is the best memory from my childhood,” another patron says. “My dad and I watched the 49ers win the Super Bowl there. The Irish bartenders knew as much about football as the guys on TV, but their commentary was a lot more colorful.”

Perry’s is such a part of San Francisco life that it’s almost a surprise to learn there is, indeed, a Perry—Perry Butler. From his first restaurant, he has pushed outward through the years, setting up branches in the suburbs and at sports stadiums. Sometimes, he’s retreated. At present, in addition to the original, there’s another Perry’s in the financial district, one at the airport and a small, stylish outlet next to the complex where the city’s leading interior designers work. Never still, Butler, as he nears 70, has another establishment opening up in Marin County, inhabiting an old country inn in Larkspur.

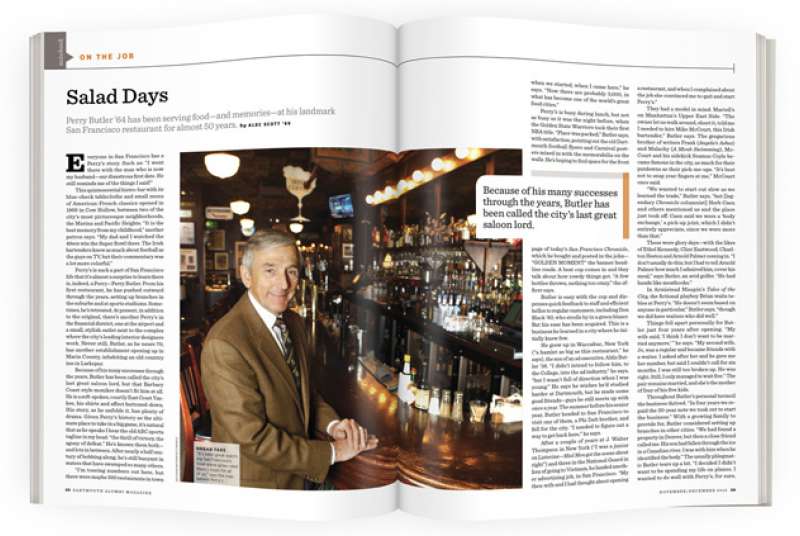

Because of his many successes through the years, Butler has been called the city’s last great saloon lord, but that Barbary Coast-style moniker doesn’t fit him at all. He is a soft-spoken, courtly East Coast Yankee, his shirts and affect buttoned-down. His story, as he unfolds it, has plenty of drama. Given Perry’s history as the ultimate place to take in a big game, it’s natural that as he speaks I hear the old ABC sports tagline in my head: “the thrill of victory, the agony of defeat.” He’s known them both—and lots in between. After nearly a half century of bobbing along, he’s still buoyant in waters that have swamped so many others.

“I’m tossing numbers out here, but there were maybe 300 restaurants in town when we started, when I came here,” he says. “Now there are probably 3,000, in what has become one of the world’s great food cities.”

Perry’s is busy during lunch, but not as busy as it was the night before, when the Golden State Warriors took their first NBA title. “Place was packed,” Butler says, with satisfaction, pointing out the old Dartmouth football flyers and Carnival posters mixed in with the memorabilia on the walls. He’s hoping to find space for the front page of today’s San Francisco Chronicle, which he bought and posted in the john—“GOLDEN MOMENT” the banner headline reads. A beat cop comes in and they talk about how rowdy things got. “A few bottles thrown, nothing too crazy,” the officer says.

Butler is easy with the cop and dispenses quick feedback to staff and efficient hellos to regular customers, including Don Black ’60, who strolls by in a green blazer. But his ease has been acquired. This is a business he learned in a city where he initially knew few.

He grew up in Waccabuc, New York (“a hamlet as big as this restaurant,” he says), the son of an ad executive, Aldis Butler ’36. “I didn’t intend to follow him, to the College, into the ad industry,” he says, “but I wasn’t full of direction when I was young.” He says he wishes he’d studied harder at Dartmouth, but he made some good friends—guys he still meets up with once a year. The summer before his senior year, Butler headed to San Francisco to visit one of them, a Phi Delt brother, and fell for the city. “I needed to figure out a way to get back here,” he says.

After a couple of years at J. Walter Thompson in New York (“I was a junior on Listerine—Mad Men got the scene about right”) and three in the National Guard in lieu of going to Vietnam, he landed another advertising job, in San Francisco. “My then-wife and I had thought about opening a restaurant, and when I complained about the job she convinced me to quit and start Perry’s.”

They had a model in mind: Martell’s on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. “The owner let us walk around, shoot it, told me I needed to hire Mike McCourt, this Irish bartender,” Butler says. The gregarious brother of writers Frank (Angela’s Ashes) and Malachy (A Monk Swimming), McCourt and his sidekick Seamus Coyle became famous in the city, as much for their putdowns as their pick-me-ups. “It’s best not to snap your fingers at me,” McCourt once said.

“We wanted to start out slow as we learned the trade,” Butler says, “but [legendary Chronicle columnist] Herb Caen and others mentioned us and the place just took off. Caen said we were a ‘body exchange,’ a pick-up joint, which I didn’t entirely appreciate, since we were more than that.”

These were glory days—with the likes of Ethel Kennedy, Clint Eastwood, Charlton Heston and Arnold Palmer coming in. “I don’t usually do this, but I had to tell Arnold Palmer how much I admired him, cover his meal,” says Butler, an avid golfer. “He had hands like meathooks.”

In Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City, the fictional playboy Brian waits tables at Perry’s. “He doesn’t seem based on anyone in particular,” Butler says, “though we did have waiters who did well.”

Things fell apart personally for Butler just four years after opening. “My wife said, ‘I think I don’t want to be married anymore,’ ” he says. “My second wife, Jo, was a regular and became friends with a waiter. I asked after her and he gave me her number, but said I couldn’t call for six months. I was still too broken up. He was right. Still, I only managed to wait five.” The pair remains married, and she’s the mother of four of his five kids.

Throughout Butler’s personal turmoil the business thrived. “In four years we repaid the 20-year note we took out to start the business.” With a growing family to provide for, Butler considered setting up branches in other cities. “We had found a property in Denver, but then a close friend called me. His son had fallen through the ice in a Canadian river. I was with him when he identified the body.” The usually phlegmatic Butler tears up a bit. “I decided I didn’t want to be spending my life on planes. I wanted to do well with Perry’s, for sure, but to watch my kids grow up.”

Four of his kids now work in various capacities at Perry’s. “I never encouraged them to join but am so happy they have,” he says. One of them, Margie ’02, helped manage the original location for a time and now focuses on human relations, marketing and getting the new Marin County location up and running. “My father knows every employee’s name,” she says. “It doesn’t matter if you’re a dishwasher, a bartender or just a guy who comes in for lunch every Tuesday, Perry will call you by name.” He encouraged two of his children to take the lead in setting up the downtown branch in 2008. “It’s the most impactful lunch in the city,” he boasts, “with Salesforce, the Gap and Google nearby and the big tech executives who look like they’re dressed for the beach.”

His restaurants have kept him in the thick of San Francisco’s lively political scene—the Democrat counts both California senators, Barbara Boxer and Dianne Feinstein, as friends. “We have celebrity bartenders for our anniversaries, and you couldn’t get Dianne out from behind the bar,” Butler says. With input from his children and others, he’s tweaked his formula through the years but never chucked it out and started afresh. “A beloved neighborhood institution which…boasts a multigenerational following,” is one San Francisco Magazine writer’s succinct description of Perry’s position in, well, the local food chain.

Around Butler, San Francisco has become a town of shared small plates, with hipster waiters reading out lengthy specials with bits of disparagement in their voices—“it’s accented with sorrel foraged in the Russian River Valley.” In that context, there’s an “aah” to a meal at Perry’s—it’s comfort food, yes, but it’s crisp, never slovenly. “We’ve only ever used quality ingredients—Roquefort cheese from France, the best hamburger meat we can buy, good wines,” says Butler. “Consistency was something we worked at. It needs to be the same good Cobb salad each time you come. It’s been great watching San Francisco’s food scene grow—and there’s room for all of us. But, as a restaurant, a person, you have to know who you are.”

Alec Scott is an award-winning freelance writer based in the Bay Area. His work has been published in the San Francisco Chronicle, San Francisco Magazine and Toronto Life.