As the outbreak of World War I loomed in 1914, campus life went on, seemingly undisturbed. The French Club announced a summer trip to Paris and alumni contributed $1,000 for a Dartmouth-sponsored mission school in Turkey.

From the beginning of the war in Europe, though, Dartmouth students debated the American role in the conflict. At first humanitarian sympathy and isolationist sentiment prevailed on campus, as in the rest of the country. In front of a student audience, President Ernest Fox Nichols applauded U.S. President Woodrow Wilson for sparing young Americans from the bloodshed that “millions of young [European] men not far from your own years and experience face.” Early in the war the general attitude was detached and even light-hearted at times. The Dartmouth published an obituary of a visiting professor killed in combat in France without much fanfare, sandwiched between advertisements. Joe Domato’s barbershop jokingly advertised, “No more neutrals! Italy has declared war on long hair. Come in and get cut up. Special attention to Germans and Austrians.”

Beginning in 1915 American colleges and universities started to take positions on the conflict. Columbia students opposed militarism. Princeton and Harvard assembled military training units. David Barton Kinne, class of 1915 and editor of The Dartmouth, argued “a mental alarm clock” was ringing for Dartmouth students to decide which path the College should follow. He urged military training on campus: “The call for service has been sounded. The need is actual and progressive; the stark misery on the European battlefield is more than we can even imagine. The College has been asked to help allay the misery, to serve the human race.”

Most students, however, favored neutrality. In May Dartmouth’s Polity Club hung a petition to President Wilson in the dining hall calling for “unbiased neutrality…in the promotion of a keener international morality among states.” One thousand undergraduates, roughly two-thirds of the student body, signed the petition for peace.

Nonetheless, many Dartmouth faculty, staff and students supported humanitarian relief and contributed funds to send two fully equipped motor ambulances and undergraduate volunteers to Paris. One of these undergrads, Richard Hall, class of 1915, who died on Christmas Day 1915 and is memorialized by a bronze bas-relief in Baker Library, was the first Dartmouth man to die in the conflict. News of his death and the massive loss of life in Europe was sobering. (During the first week of November, nearly 100 years after his death, his descendants and other ambulance drivers will remember Hall in Alsace, France, where he is buried in the town cemetery at Moosch.)

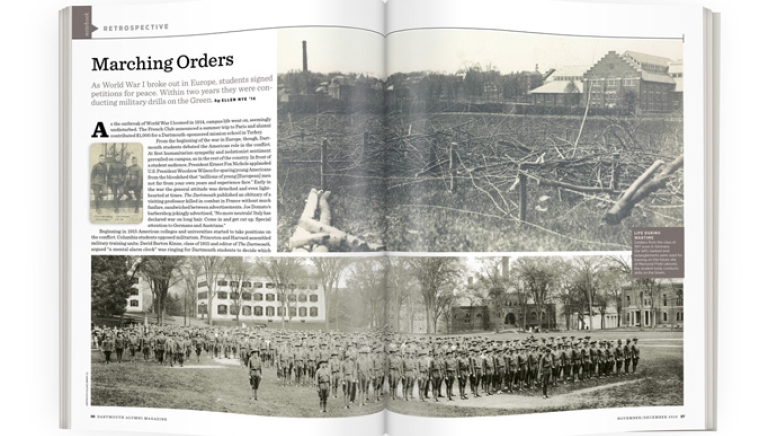

In December of 1915, with student sentiment divided, President Nichols announced his support for extracurricular, noncompulsory drill on campus. Two months later hundreds of Dartmouth students held their first military session.

When trustees added military drill to the 1916 summer session curriculum, Jack-O-Lantern editor Francis Stirling Wilson, class of 1916, was infuriated. He published an editorial that disparaged College administrators, suggesting the College would next give “credit for keg parties and honorable mention for attendance at Junction dances….Take notice alumni, and take notice other colleges, that my diploma is not as good as yours!”

Wilson was suspended from the College. A petition signed by 1,000 students failed to secure his immediate reinstatement. He did, however, eventually receive his degree.

By the fall of 1916, when Ernest Martin Hopkins, class of 1901, succeeded Nichols as president, much of campus seemed to support military preparedness at Dartmouth and American preparedness more broadly. The Democratic Party renominated Wilson under the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War,” but this platform held little appeal for Dartmouth students. In a straw poll they supported his opponent, Charles Evans Hughes, with 422 votes, while Wilson received only 239. The faculty, however, supported Wilson 45 to 25.

German attacks on American ships further angered the student body. In a March 1917 straw poll, 87 percent of students believed Wilson should take a stand against Germany to protect American neutrality rights on the seas. Twenty-one percent of students believed that the German actions already justified a declaration of war. More than half of the students supported universal compulsory military training in the United States.

On April 2, 1917, Wilson declared war. Within weeks more than 160 Dartmouth men had left campus for active service.Hopkins remained committed to Dartmouth’s educational mission, but the war drastically changed the College. In the fall of 1917 only about 1,000 of 1,500 students remained on campus, and most of them were training for war on a football field covered with trenches and barbed wire.

Just weeks before the November 11, 1918, end of the war, the Student Army Training Corps program organized by the U.S. War Department took over 516 colleges, including Dartmouth. All regular classes were suspended and the undergraduates were considered active-duty soldiers, subject to strict military rules. After just two months, on December 9, 1918, only four weeks after the signing of the armistice ending WW I, the College announced it was returning “to peaceful academic pursuits.”

In all, 3,407 Dartmouth alumni and undergraduates served in the conflict—and 112 died.

Ellen Nye, a Fulbright Scholar, studies social and economic history at Cambridge University.