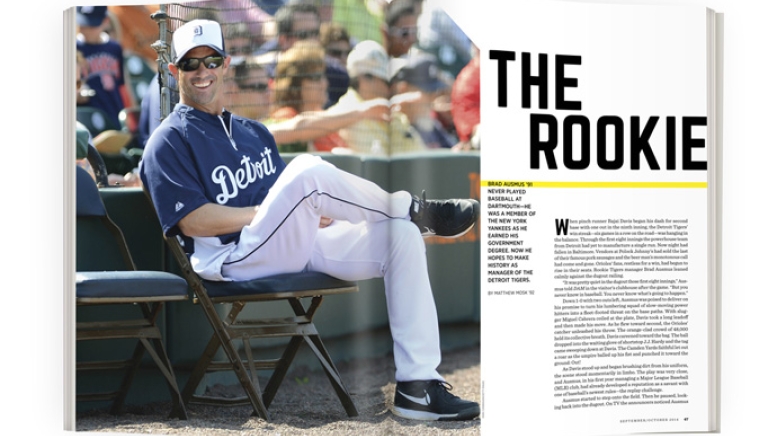

When pinch runner Rajai Davis began his dash for second base with one out in the ninth inning, the Detroit Tigers’ win streak—six games in a row on the road—was hanging in the balance. Through the first eight innings the powerhouse team from Detroit had yet to manufacture a single run. Now night had fallen in Baltimore. Vendors at Polock Johnny’s had sold the last of their famous pork sausages and the beer man’s monotonous call had come and gone. Orioles’ fans, restless for a win, had begun to rise in their seats. Rookie Tigers manager Brad Ausmus leaned calmly against the dugout railing.

“It was pretty quiet in the dugout those first eight innings,” Ausmus told DAM in the visitor’s clubhouse after the game. “But you never know in baseball. You never know what’s going to happen.”

Down 1-0 with two outs left, Ausmus was poised to deliver on his promise to turn his lumbering squad of slow-moving power hitters into a fleet-footed threat on the base paths. With slugger Miguel Cabrera coiled at the plate, Davis took a long leadoff and then made his move. As he flew toward second, the Orioles’ catcher unleashed his throw. The orange-clad crowd of 48,000 held its collective breath. Davis careened toward the bag. The ball dropped into the waiting glove of shortstop J.J. Hardy and the tag came sweeping down at Davis. The Camden Yards faithful let out a roar as the umpire balled up his fist and punched it toward the ground: Out!

As Davis stood up and began brushing dirt from his uniform, the scene stood momentarily in limbo. The play was very close, and Ausmus, in his first year managing a Major League Baseball (MLB) club, had already developed a reputation as a savant with one of baseball’s newest rules—the replay challenge.

Ausmus started to step onto the field. Then he paused, looking back into the dugout. On TV the announcers noticed Ausmus glancing back at his bench coach Gene Lamont. “Ausmus is trying to decide what to do here,” the color man said. Then the young manager calmly stepped back onto the field and began the slow walk toward home plate. “And, yes,” the announcer said, “we will get the challenge.”

The number of decisions a baseball manager makes to change the course of a game is almost infinite. Few are as direct as the manager’s challenge at a pivotal point in a ball game. When Ausmus, 45, took over as skipper of the Tigers this year, the sum total of his managerial experience was the two weeks he coached the Israeli national baseball team in 2012. One might think he could be afforded some time to break into the job, but that would display ignorance of life at the helm of a major league club. “Nowadays every move you make is questioned ad nauseam on every TV show, on the radio outlets, on the talk shows, in the newspapers, and then you have the blogs and the Internet,” says Phil Garner, who managed three teams in 15 years, including Detroit and Houston squads that had Ausmus in their lineups. “Trying to control that is the toughest thing the manager has to do today.”

It is into that blazing spotlight that Ausmus has ventured, starting a second phase of what may be one of the most successful and long-lasting baseball careers for any Dartmouth graduate. A number of professional ballplayers have passed through Hanover since Red Rolfe ’31 was a four-time All Star in the 1930s with the Yankees and later, like Ausmus, became manager of the Tigers. Yankees pitcher Jim Beattie ’76, who with the Yankees threw a nine-inning gem to win Game 5 of the 1978 World Series, also played for the Seattle Mariners before going into front-office management. But Ausmus is the first in baseball’s modern era to tackle both the challenges of the playing field and the bench, and he is doing so at a time of great change in his sport. His success as a player is beyond dispute: During an 18-year career he caught more games (1,938) than all but six players in the history of modern baseball. His ability to manage a major league club, however, remained largely untested on this steamy night in Baltimore. It was just beginning to be scrutinized and dissected by tens of thousands of armchair experts. After more than 20 years in professional baseball, having made it from the minors to the majors, from the playing field through front office jobs, Ausmus is right back where he started: He’s a rookie with swagger and something to prove.

Harry Ausmus was toiling as a professor of European history at Southern Connecticut State when he came home one evening and his precocious son Brad, then just 5 years old, had an announcement to make. “He turned to me and said when he grew up he wanted to go to Dartmouth and he wanted to play baseball,” Harry recalls.

The senior Ausmus said he gave his son a lecture about having to work hard and told him if he did, he could do both. He attributed his son’s interest in Dartmouth to the Foster family (Stephen ’53, Tom ’77 and Bob ’79) living across the street in Cheshire, Connecticut, and says he gave the conversation little thought as Brad grew older. But as his son excelled at school, Harry grew increasingly confident that Dartmouth was in reach. Not being particularly athletic himself, Harry says, he didn’t harbor any dreams for his son in professional sports. If anything, Brad’s mother, Linda, says, Brad seemed to enjoy basketball most—perhaps because the Foster boys used to let him play one-on-one riding atop one or the other brother’s shoulders. “But he didn’t get what he needed genetically,” she notes of her 5-foot-11-inch son. It was only after the fact that Harry learned pro scouts had been lingering in the bleachers at Cheshire High School’s baseball field.

Recruiters from Dartmouth, Harvard and Princeton pursued Brad as a catcher. So did the New York Yankees. When Ausmus learned he had been drafted in the 47th round during his senior year in high school, it set the stage for an enormous decision: college or baseball. A recent Fox Sports survey found only 4 percent of major league players hold a four-year college degree. There is a reason for that, explains Dartmouth coach Bob Whalen (who arrived in Hanover Ausmus’ junior year). A minor league baseball schedule is enormously taxing, and most university fall terms start before the season ends. Although some students can nurture the interest of pro scouts through some or all of a college career, young prospects always have to worry that the chance to go pro is a narrow window.

For Ausmus the choice was especially difficult because his parents were very clear about his future. “It was kind of implied that I should get my degree,” Ausmus says.

“I was adamant,” his father says.

At first Ausmus turned down the contract offer from the Yankees and enrolled in Dartmouth. The next day, though, he and his mother were on a long drive home from a summer trip to Cape Cod and Brad was unusually quiet.

“He turned to me and said if he didn’t sign he might never have another chance,” his mother says. When they walked into the house, Brad called the Yankees. A scout drove out that night with the contract, and Brad signed it.

The expectations had been drummed into Ausmus from the age of 5: He could freely pursue his dream of a baseball career as long as he also pursued his Dartmouth degree. He would just have to find a way to do both.

When the parents of John Ross ’91 dropped him off at Dartmouth for freshman orientation in the fall of 1987, he found himself standing alone in his room on the fourth floor of Andres Hall. He wasn’t quite sure what to do next, so he wandered over to the baseball offices to see Mike Walsh, the coach who had recruited him and the only person he knew on campus. When he walked into Walsh’s office, there was Ausmus on the coach’s couch.

Bonds quickly formed between the baseball team and Ausmus, who was ineligible to play college ball because of his Yankees contract.

“In a strange way, we didn’t really think of him as a baseball player at first,” Ross says. “We heard all these things about him. We knew he had been signed. Our coach raved about how incredible he was. But to us he wasn’t really a player because we had never seen him play.”

The irony is not lost on Coach Whalen: Ausmus may well be the best baseball player ever to attend Dartmouth and never play a single inning in a Big Green uniform.

It was not long, though, before Ausmus’ friends started to see what had captured the attention of the Yankees scouts. Ross recalls the day when Ausmus joined a group of Dartmouth catchers in a drill to practice throws to second base. Ross, a second baseman, moved into his spot, straddling the bag while, one at a time, catchers whipped the ball across the infield and into his glove.

“The catchers on the team were very good,” Ross says. “Each one, when they threw the ball, it had a slight little arc as it came over the infield. I remember when Brad first came in, the moment my glove came down, there was the ball. No arc. It hit me right in the wrist. We saw what made him different.”

What also made Ausmus different were the long stretches of time when his baseball friends didn’t see him. For Ausmus, the Dartmouth Plan created the answer to the puzzle his father had advised him he needed to solve: how to attend Dartmouth and play minor league ball.

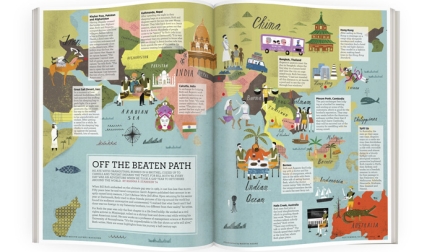

After his freshman year Ausmus adjusted his schedule to spend fall and winter terms on campus, taking four courses each term. In spring he headed to Florida to train with the Yankees. After freshman year it was rookie league ball in Florida. In 1989, after two terms as a sophomore, it was “lower A” ball with the Oneonta [New York] Yankees. In 1990, after more courses in Hanover, Ausmus joined the “upper A” Prince William [Virginia] Cannons. In 1991 it was the “AA” Albany-Colonie [New York] Yankees. By the time he was about to graduate, Ausmus had joined the “AAA” team, the Columbus [Ohio] Clippers.

“With every move up, you breathed a sigh of relief,” Linda Ausmus says.

Incredibly, the double life enabled Ausmus to have what could be described as a typical Dartmouth experience. As a government major he excelled. Emeritus government professor Roger Masters calls him “one of the five or ten best” students to ever pass through his classroom. “His papers and exams were always both exact and thoughtful, and he was always well prepared for class, clearly having done the readings,” Masters says. Ausmus also moved effortlessly in the baseball team’s social circles, centered largely on Chi Gamma Epsilon. Classmate Ross recalls a winter evening when he and teammates were in the living room and began hearing a “pop, pop” sound on the windows. Brothers from Phi Delt had begun pelting the house with snow. An enormous snowball fight erupted. Eventually, Ausmus lifted himself off the couch and stepped onto the porch. He grabbed a wad of snow and spotted, all the way across the lawn, a laughing Phi Delt student. Ausmus let it fly. Like a mortar round, the snowball exploded on the boy’s back with a thump. “Once someone roused Ausmus from the house, the fight was over,” Ross says.

Ausmus says Sophomore Summer was the only element of the typical Dartmouth tenure he missed out on. His truncated schedule also meant it took him five and a half years to graduate.

Last fall Ausmus returned to Hanover for the first time since graduation. He wanted his daughter, a high school sophomore, to see the campus that held so many positive memories for him. “I ate at Molly’s. I saw EBAs, where we used to get the late-night chicken sandwiches. I went over to Chi Gam. It was [before the term started], so it was relatively empty, but I went inside and walked around. It looked the same.”

His mother says Brad may have enjoyed the trip more than her granddaughter, who has grown up in California: “She liked the school, but she kept saying, ‘It doesn’t look like this in the winter, does it?’ ”

In 2004, the year Garner took over as manager of the Houston Astros, where Ausmus was midway through his second stint as catcher, Garner had developed a rhythm where early each day one of his assistants placed an advanced scouting report on his desk so it would be the first thing he read when he arrived at the ballpark. The document could be dozens of pages long, a compilation of the observations of his scouts and the drilled-down statistics compiled by a company that charts every pitch thrown in baseball. The report provided details on the tendencies of every batter and pitcher his squad would be facing that night.

One morning Garner arrived at the ballpark and the report wasn’t in its usual spot, but when he returned with his morning coffee it was there. The next day, it happened again. “It was real strange,” Garner says. “I started noticing the reports weren’t coming straight to my desk.” Garner finally realized what had happened when Ausmus started rattling off details about the opposing players at the “pitchers and catchers” meeting.

“Brad was getting to the ballpark earlier in the day so he could intercept the reports,” Garner says, “so he knew everything he could by the time we went into that meeting.”

That level of preparation and dedication to detail may help explain how he endured for 18 years in a game that chews up most players in half that time—especially catchers.

Although he was discovered by the Yankees, Ausmus was snatched by the Colorado Rockies in the 1992 expansion draft and assigned to their Colorado Springs minor league team. In 1993 the Rockies dealt Ausmus to the San Diego Padres, where he made his big league debut going one-for-three. A career .251 hitter, Ausmus spent the bulk of his career with the Tigers and Astros, where he became best known for his arm, durability and command of the game. He won three gold gloves, appeared in the 1999 All-Star game and played a stout four games behind the plate in the 2005 World Series, even though his team was swept.

What the back of his baseball card fails to credit him with is comporting himself with maturity in an environment where money, groupies and other temptations regularly provide scandal-sheet fodder.

Ausmus and wife Liz married in 1995 and have two daughters, Sophie, 16, and Abigail, 15, who have spent most of their father’s career living near San Diego. Friends said they suspect the reason Ausmus took a few years away from the field when his playing career ended—and he worked close to home in the Padres’ front office—was so he could make up for lost time with his girls. (When interviewed by DAM in 2003 he was at home, tending to his daughters’ Barbie dolls.)

Ausmus commanded a hefty seven-figure salary for most of his career. Add to that his chiseled features and youthful air of confidence (female Tigers fans have flooded the blogosphere with comments about his appearance and launched a groupie Twitter account with the handle @sexyausmus), and some people might consider his sedate family life miraculous. Ross, who works at IBM and remains one of Ausmus’ closest friends, says Ausmus somehow managed to remain level during his playing years.

“When I hung out with him with big league players, most of those guys would pick on us as nerds and geeks,” Ross says. “I think that’s part of why he really values his time at Dartmouth. I think it helps keep him grounded.”

Ausmus can’t pinpoint when during his playing years he started to entertain the idea of managing. Garner jokes that “any time you’re hitting below .230, you’re a premature candidate for manager.”

Repeatedly Ausmus was cited in blogs and news stories as one of the league’s brightest players. No question the Ivy League background helped, says Beattie, who spent nine seasons in the majors as a player, 10 as a general manager and is today a scout for the Toronto Blue Jays. But so did Ausmus’ work behind the plate. “Catchers have a natural thinking process, they study the game from that position, they’re involved in many parts of the game in a way that others are not,” Beattie says.

Ausmus agrees: “You learn game management. You have to know who is up, who’s on deck. You have to plan two or three hitters ahead as you’re calling pitches. It also often gets overlooked that catcher is the one position that has to both deal with the pitchers and also understand what it’s like to be an everyday position player,” Ausmus says.

Garner, who is now retired, specifically recalls an Ausmus game in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, when his bench manager, Cecil Cooper, was out of town. In the sixth inning Garner argued one too many calls and got tossed from the game. As they rolled into extra innings Ausmus began running back and forth into the visitors’ clubhouse to update Garner on the latest twists and await instructions. “I said to him, ‘Well, what would you do?’ ” Garner recalls. “And he said this and this and this. And I told him, ‘Okay, go ahead.’ I was letting him call the shots. He was having the time of his life.”

As Ausmus’ playing years neared an end, the idea of him managing his own team had gained currency. His last stop in baseball was as backup catcher for the L.A. Dodgers. Ausmus found himself studying manager Joe Torre’s every move. “I would sit in the dugout, sit on the bench and try and think along with what was happening in the game,” Ausmus says.

Torre, another former catcher, must have noticed, because when the Tigers began hunting for a replacement for the legendary Jim Leyland, Torre called their general manager with a list that had only one name on it.

Back on the field in Baltimore, the scoreboard was flashing, “Play Under Review.” The head umpire had a headset on and was ducked under a hood so he could see the video monitor showing the replay of the runner’s slide into second base. The ruling would come from MLB officials in New York, but as the slow motion played out on the jumbotron, Ausmus’ decision to challenge the call began to appear a wise one. From one angle in particular it appeared clear that the fleet-footed runner’s outstretched fingertips touched the bag just before the glove swept down into his chest. The umpire stepped back out to home plate and signaled the call: Safe!

The Orioles crowd booed lustily while Ausmus, back at his perch on the dugout railing, calmly looked on. With the tying run now at second, Miguel Cabrera launched a three-run home run onto Eutaw Street.

“I think that replay decision was the biggest moment of the season for Ausmus to that point because it turned the game,” says George Sipple, who covers the Tigers for the Detroit Free Press. “He went for it, and he was right.”

When the Tigers announced they had hired a new skipper who had never managed a ball club before, Sipple says there was initial hesitation. But the more people he interviewed, the more he started to see what the Tigers saw.

“I spoke with someone who told me Brad knows $50 words but he is smart enough to know he doesn’t have to use them,” Sipple says.

Some Detroit faithful thought the young Ivy Leaguer was being brought in to increase the team’s reliance on Sabermetrics, the stat-driven craze made famous in the book and movie Moneyball. In fact, Ausmus has been something of a moderate when it comes to relying on numbers. He says the art to using statistics is boiling them down to the two or three pieces of information that a player will use and not filling his head with numbers he won’t.

Whatever his formula, so far, it’s working.

At the helm of a World Series contender, Ausmus appears to be handling the blazing spotlight with a laid-back ease that is deeply ingrained. As his mother puts it, “He’s so calm it’s like he’s comatose.” The fans appear comfortable with his subtle reshuffling of the team. And even the regular beat writers who might be quick to pick him apart seem content with the job he’s been doing. “There hasn’t been a moment where you thought, ‘Oh, that’s a rookie mistake.’ ” Sipple says. “I haven’t heard anyone say, ‘I don’t know why we gambled on that play,’ or, ‘I don’t know why he made that call.’ ”

The true test of a manager comes at the end of the summer, not the beginning. The Tigers made the playoffs in four of the last eight seasons, only to be disappointed. Those who knew Ausmus at Dartmouth would not be surprised by his reply when asked what would make his rookie season as skipper a success.

“It’s tough to rate a successful season in baseball because there are so many variables,” Ausmus says. “But in my mind this team has the personnel to win the World Series. So that’s the goal. You gotta have something to aim for.”

Matthew Mosk is an Emmy Award-winning investigative reporter for ABC News and a regular contributor to DAM.