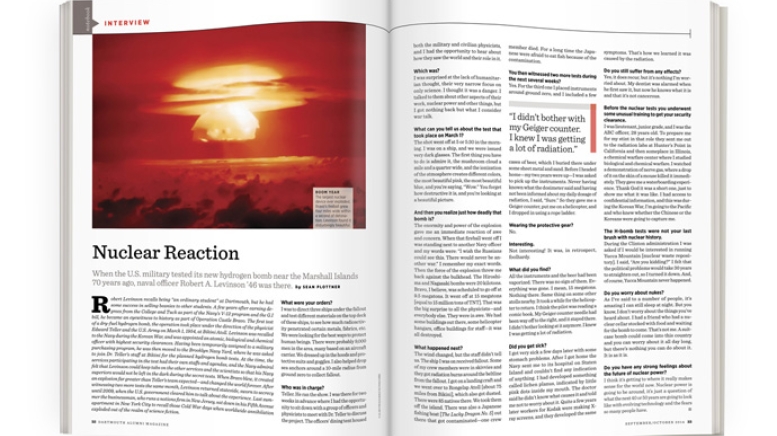

Robert Levinson recalls being “an ordinary student” at Dartmouth, but he had some success in selling beanies to other students. A few years after earning degrees from the College and Tuck as part of the Navy’s V-12 program and the G.I. bill, he became an eyewitness to history as part of Operation Castle Bravo. The first test of a dry-fuel hydrogen bomb, the operation took place under the direction of the physicist Edward Teller and the U.S. Army on March 1, 1954, at Bikini Atoll. Levinson was recalled to the Navy during the Korean War, and was appointed an atomic, biological and chemical officer with highest security clearances. Having been temporarily assigned to a military purchasing program, he was then moved to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where he was asked to join Dr. Teller’s staff at Bikini for the planned hydrogen bomb tests. At the time, the services participating in the test had their own staffs and agendas, and the Navy admiral felt that Levinson could keep tabs on the other services and the scientists so that his Navy superiors would not be left in the dark during the secret tests. When Bravo blew, it created an explosion far greater than Teller’s team expected—and changed the world forever. After witnessing two more tests the same month, Levinson returned stateside, sworn to secrecy until 2009, when the U.S. government cleared him to talk about the experience. Last summer the businessman, who runs a notions firm in New Jersey, sat down in his Fifth Avenue apartment in New York City to recall those Cold War days when worldwide annihilation exploded out of the realm of science fiction.

What were your orders?

I was to direct three ships under the fallout and test different materials on the top deck of these ships, to see how much radioactivity penetrated certain metals, fabrics, etc. We were looking for the best ways to protect human beings. There were probably 9,000 men in the area, many based on an aircraft carrier. We dressed up in the hoods and protective suits and goggles. I also helped drop sea anchors around a 10-mile radius from ground zero to collect fallout.

Who was in charge?

Teller. He ran the show. I was there for two weeks in advance where I had the opportunity to sit down with a group of officers and physicists to meet with Dr. Teller to discuss the project. The officers’ dining tent housed both the military and civilian physicists, and I had the opportunity to hear about how they saw the world and their role in it.

Which was?

I was surprised at the lack of humanitarian thought, their very narrow focus on only science. I thought it was a danger. I talked to them about other aspects of their work, nuclear power and other things, but I got nothing back but what I consider war talk.

What can you tell us about the test that took place on March 1?

The shot went off at 5 or 5:30 in the morning. I was on a ship, and we were issued very dark glasses. The first thing you have to do is admire it, the mushroom cloud a mile and a quarter wide, and the ionization of the atmosphere creates different colors, the most beautiful pink, the most beautiful blue, and you’re saying, “Wow.” You forget how destructive it is, and you’re looking at a beautiful picture.

And then you realize just how deadly that bomb is?

The enormity and power of the explosion gave me an immediate reaction of awe and concern. When that fireball went off I was standing next to another Navy officer and my words were: “I wish the Russians could see this. There would never be another war.” I remember my exact words. Then the force of the explosion threw me back against the bulkhead. The Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs were 20 kilotons. Bravo, I believe, was scheduled to go off at 9.5 megatons. It went off at 15 megatons [equal to 15 million tons of TNT]. That was the big surprise to all the physicists—and everybody else. They were in awe. We had some buildings out there, some helicopter hangars, office buildings for staff—it was all destroyed.

What happened next?

The wind changed, but the staff didn’t tell us. The ship I was on received fallout. Some of my crew members were in skivvies and they got radiation burns around the beltline from the fallout. I got on a landing craft and we went over to Rongelap Atoll [about 75 miles from Bikini], which also got dusted. There were 85 natives there. We took them off the island. There was also a Japanese fishing boat [The Lucky Dragon No. 5] out there that got contaminated—one crew member died. For a long time the Japanese were afraid to eat fish because of the contamination.

You then witnessed two more tests during the next several weeks?

Yes. For the third one I placed instruments around ground zero, and I included a few cases of beer, which I buried there under some sheet metal and sand. Before I headed home—my two years were up—I was asked to pick up the instruments. Never having known what the dosimeter said and having not been informed about my daily dosage of radiation, I said, “Sure.” So they gave me a Geiger counter, put me on a helicopter, and I dropped in using a rope ladder.

Wearing the protective gear?

No.

Interesting.

Not interesting! It was, in retrospect, foolhardy.

What did you find?

All the instruments and the beer had been vaporized. There was no sign of them. Everything was gone. I mean, 15 megatons. Nothing there. Same thing on some other atolls nearby. It took a while for the helicopter to return. I think the pilot was reading a comic book. My Geiger counter needle had been way off to the right, and it stayed there. I didn’t bother looking at it anymore. I knew I was getting a lot of radiation.

Did you get sick?

I got very sick a few days later with some stomach problems. After I got home the Navy sent me to its hospital on Staten Island and couldn’t find any indication of anything. I had developed something called lichen planus, indicated by little pink dots inside my mouth. The doctor said he didn’t know what causes it and told me not to worry about it. Quite a few years later workers for Kodak were making X-ray screens, and they developed the same symptoms. That’s how we learned it was caused by the radiation.

Do you still suffer from any effects?

Yes, it does recur, but it’s nothing I’m worried about. My dentist was alarmed when he first saw it, but now he knows what it is and that it’s not cancerous.

Before the nuclear tests you underwent some unusual training to get your security clearance.

I was lieutenant, junior grade, and I was the ABC officer, 28 years old. To prepare me for my stint in that role they sent me out to the radiation labs at Hunter’s Point in California and then someplace in Illinois, a chemical warfare center where I studied biological and chemical warfare. I watched a demonstration of nerve gas, where a drop of it on the skin of a mouse killed it immediately. They gave me a waterboarding experience. Thank God it was a short one, just to show me what it was like. I had access to confidential information, and this was during the Korean War, I’m going to the Pacific and who knew whether the Chinese or the Koreans were going to capture me.

The H-bomb tests were not your last brush with nuclear history.

During the Clinton administration I was asked if I would be interested in running Yucca Mountain [nuclear waste repository]. I said, “Are you kidding?” I felt that the political problems would take 30 years to straighten out, so I turned it down. And, of course, Yucca Mountain never happened.

Do you worry about nukes?

As I’ve said to a number of people, it’s amazing I can still sleep at night. But you know, I don’t worry about the things you’ve heard about. I had a friend who had a nuclear cellar stocked with food and waiting for the bomb to come. That’s not me. A suitcase bomb could come into this country and you can worry about it all day long, but there’s nothing you can do about it. It is as it is.

Do you have any strong feelings about the future of nuclear power?

I think it’s getting to where it really makes sense for the world now. Nuclear power is going to be around, it’s just a question of what the next 40 or 50 years are going to look like with evolving technology and the fears so many people have.