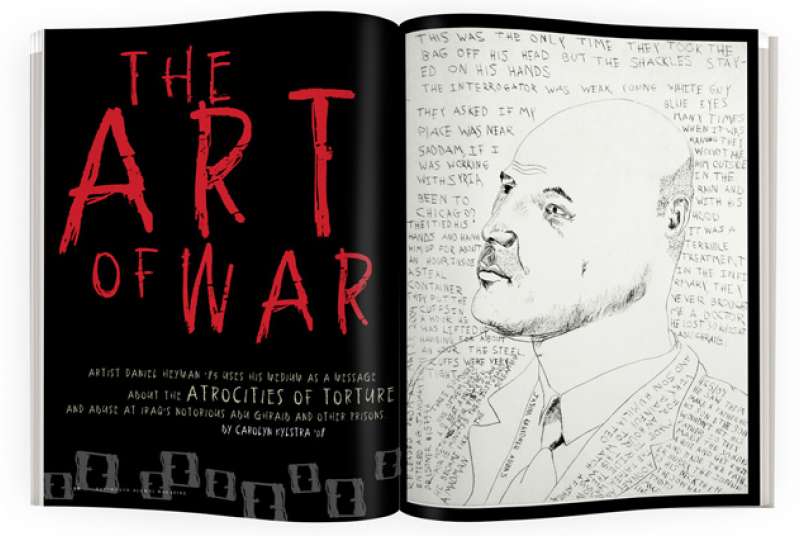

The Art of War

For the past five years artist Daniel Heyman has worked on “The Abu Ghraib Detainee Interview Project,” a collection of more than 60 copper etchings and watercolor paintings that address the human rights violations committed at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. He has heard repulsive, heartbreaking stories directly from the detainees and has sought to bring those stories to life, to force Americans to confront the disturbing and senseless reality of a war he feels they don’t think about often enough.

One deeply religious man talked about his prison guards sodomizing him with a broom handle for being “unruly”—a devout Muslim, he broke the prison rules and insisted on praying five times a day. Another man said he was kept in a 6-by-2-by-2-foot box for 16 days straight, allowed out only once a day, and the guards took pleasure in drumming on his box at half-hour intervals. One detainee’s account was of being arrested minutes after a bomb killed his two sons, ages 8 and 11: He had been holding one dead son in the air, crying unintelligibly, when the Americans arrived to arrest every adult male in the area on suspicion of setting off the explosion. He was being handcuffed on the ground when he saw that his other son had been decapitated. He was held for 148 days at Abu Ghraib before being released without being charged.

There is a lesson to be learned here, says Heyman.

Since 2006 he has traveled to the Middle East seven times, visiting first Amman, Jordan, and more recently Istanbul, where he has sat in on interviews with former Iraqi detainees. He accompanies human rights lawyer Susan Burke, who is working on behalf of the former detainees in a class-action lawsuit against various interrogators. All detainees involved in the lawsuit were held at Abu Ghraib and ultimately released without charges. Semantics of torture aside, their time at the prison was traumatic and violent, and in spite of formal military apologies, the wounds are still raw. Burke’s role is to help the victims receive legal recompense; Heyman’s objective is to provide some level of emotional justice. He sits in on the interviews and paints or etches each subject’s portrait. In the background he transcribes the detainee’s stories in a swirl of words that shock and awe. He receives no compensation from Burke for creating the artwork. It is his own project, for his own reasons.

“My aim is to bring their voices back, to give these people their humanity, to allow them to say, ‘This is what happened to me,’ ” says Heyman, who lives in Philadelphia and supplements his artistic career with teaching gigs at Swarthmore and the Rhode Island School of Design. “We have so many reports from the military one way or the other, telling us what happened. The people it happened to should be allowed to speak for themselves.”

Heyman’s interest in the effects of war began in 1986, when Dartmouth granted the visual arts major a Reynolds scholarship to travel to France and interview people about their experiences during World War II. He found that even though the people he interviewed were in their 60s and 70s, it was clear the war had had a profound effect on their lives. “What happens in a war or a violent episode in someone’s life remains in that life,” Heyman says.

His goal is to portray this understanding in his art. He believes art should not be made for the purpose of making people happy, but rather to make people think. His work appears at a variety of museums across the country and can be viewed at www.

danielheyman.com. Eight of his portraits from Amman, including the one shown on the preceding page, have been acquired by the Hood Museum.

“Artists have very little power in the world, and I can’t thank my lucky stars enough to have this opportunity,” Heyman says. “These people want some kind of justice, and part of that justice is just having their stories told.”

Carolyn Kylstra is a former DAM intern. She works at Men’s Health.