As-tu tous tes trucs…euh…toutes tes affaires?”

For more than 50 years Dartmouth students taking entry-level French have wrestled with this tongue-twisting alliterative phrase, which translates to, “Do you have all your stuff…uh…all your things?” It is also infamous among the teaching assistant (TA) drill instructors. I know this because having spent a term abroad in the winter of 1975, I wanted to become a TA. As a history major, I was a longshot. Seventy-five students were vying for 14 spots. Twenty-one had been a TA before—and most were language majors.

The drill is a unique language instruction method developed by the insanely charismatic Dartmouth professor John Rassias, who was Rosetta Stone before there was Rosetta Stone. To train potential instructors, Rassias held a four-day crash course in Dartmouth Hall before each term that culminated in a trial-by-fire where applicants taught a mock class in front of the Romance languages faculty. As contestants, we would be graded on our mastery of the Rassias method, our pronunciation skills, and our ability to correct student mistakes.

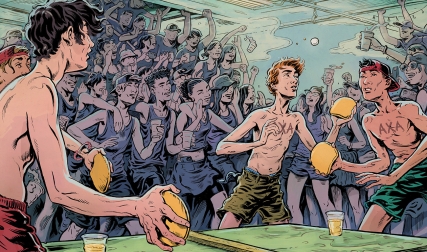

The method is an in-your-face teaching style that uses repetition to teach scenarios by reverse-engineering the sentences from the last clause back to the first. To call on students, we’d snap our fingers and point, usually with some misdirection or head fake to keep them on their toes. Mistakes were not to be tolerated. If a student gave the wrong answer: Snap! We’d call on someone else to give the correct answer. The idea was to keep everyone thinking—even if they weren’t called upon. It’s high speed, high intensity, and high stress.

The repetition of the phrases and the snaps set a rhythm as we moved across the room to confront each seated student at three levels. The instructor level (standing upright), the peer level (eye-to-eye) and the submissive level (kneeling). Each level had a purpose: to instruct, to listen, to coax. We were expected to weave in all three.

So why is the phrase, “As-tu tous tes trucs…euh…toutes tes affaires?” so infamous?

“Whatever you do, don’t use that sentence for your trial,” a senior TA warned the practicing contestants. “It contains four words using two different ‘u’ sounds, and one follows a French ‘r.’ It’s difficult to pronounce correctly and hard to hear when a student gets it wrong. For the trial, it’s a minefield. Avoid it at all costs.”

That’s why I chose to use it.

By day three of the workshop I counted only one distinct advantage over my peers: My finger snap could wake the dead. Other than that, I was just like everyone else, trying to make it look as though I knew what I was doing. I needed something to stand out among the 75.

I practiced the sentence each night in my dormitory bathroom. Classes hadn’t yet started, so I had the place to myself. The six toilet stalls were spaced about the same distance apart as seats in Dartmouth Hall, so I bobbed and weaved, calling on each seat at random. If I did it successfully, whoosh! I rewarded myself with a celebratory flush.

The day of the trial I nervously watched as each contestant stood to compete. Despite the tension, time started to drag as we watched the same scenarios being taught again and again. My name was called, and I stood to face the students—all French majors, including the senior TA who had advised us.

I spoke with a loud, clear voice: “As-tu tous tes trucs…euh…toutes tes affaires?”

Everyone in the room looked up.

“As-tu tous tes marbles?” called out the senior TA.

With a smile, I started to reverse engineer the sentence. “Toutes tes affaires?” has an easy ‘u’ sound, so I was on safe ground to start. I worked my way across the room. No one made a mistake.

Instead of turning next to the first part of the sentence, I focused on the “…euh” between the two clauses. I got confused looks. Mimicking the French, who have a way of making even pauses sound interesting, I pulled out my bottom lip to exaggerate. “Eeeuuuhh.” Everyone laughed as I overdid it. It also gave me a chance to correct student mistakes if they didn’t camp it up with me. Everyone played along.

Finally, the hard part: “As-tu tous tes trucs.” Having practiced it for three days I cleanly pronounced all three “u” sounds and snapped my way across the room.

One student mispronounced a “u.” It was something I hadn’t anticipated. I assumed everyone spoke better French than me. I had a choice: correct the French major in front of me, killing his chances for a position—and making an enemy for life—or pretend I didn’t hear it. But I knew the judges would have heard the mistake, so I had to correct it.

I snapped to the senior TA. He gave the proper pronunciation, and I snapped back to the student for his correction, only to see my death cooling in his eyes.

When I finished, everyone applauded and I took a bow. The next morning the names of the 14 winning TAs were posted. Mine wasn’t one of them. The professors had chosen their favorites. My only consolation was that Rassias soon changed the system to allow for new blood, stipulating that TAs could be hired only twice in four terms.

I tried again two terms later and made the list—and taught a total of four times. I learned most of the scenarios by heart. And every time I taught that first sentence, I couldn’t help but picture those six empty toilet stalls from my dorm’s bathroom. Whoosh!

Joe Gleason is a public relations consultant. He lives in Clifton, Virginia.