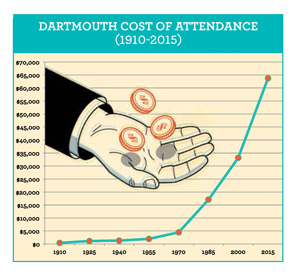

Anybody who has bought coffee through the years—or purchased movie tickets or paid for home repairs—knows a dollar doesn’t go as far as it used to. But even as prices have, predictably, drifted upward, what has happened to college tuitions in recent years has been startling. In the past two decades average tuition has more than doubled—after adjustment for inflation.

In 1994 Dartmouth tuition, room and board, and mandatory fees cost about $26,000. This fall students will face a price tag of nearly $64,000. The spike comes against a backdrop of stagnant wages in a country where median family income is $53,000, and from a not-for-profit institution whose mission is rooted in improving the world.

“The trajectory we are on is not sustainable,” says Berkeley public policy professor Robert Reich ’68, a former U.S. Secretary of Labor and College trustee. He recalls the tuition charged when he was a student—roughly $2,000—was “about the cost of a Chevrolet.”

Today it’s about the cost of a BMW M3 sedan—and there is no simple explanation for the spike. Just as lattes cost more these days, so do markers and whiteboards and keeping the lights on. Healthcare costs and salaries are rising too—and hiring at the College has shot up more than enrollment.

Less obvious pressures are also at play. To compete for top students, analysts say, Dartmouth and other elite schools have become locked in a virtual arms race, going after professors who are experts in their fields, constructing dazzling gyms with cutting-edge fitness equipment and installing the fastest-possible computer connections—not knowing for sure what makes a student choose one college over another.

Reich, for one, says that Dartmouth, like other schools, needs to take a deep breath: If it cared less about its U.S. News & World Report ranking, it might not feel as compelled to spend as much on whiz-bang amenities, which could bring costs down, he says.

Indeed, if a prospie opts for Yale, it could have nothing to do with the fact that her Hanover Inn meal disagreed with her or that the dorm room she toured didn’t have a super-sized en-suite bathroom. Yet those kinds of considerations seem to inform spending decisions.

Less sizeable but still significant drivers of cost include compliance with a range of government regulations imposed to address issues such as crime, gender equity and accessibility, which have totaled millions of dollars, College officials say. Although not as much as financial aid, such expenses have “been a driver for the last eight to 10 years,” says President Phil Hanlon ’77.

In a sense, there may be very little incentive for institutions such as Dartmouth to rein in spending. In a high-stakes, playing-hard-to-get strategy, the most exclusive schools seem to know that the more they lower their admission rates, the more students will rush to apply. As seems to be the case with so-called Veblen commodities such as diamonds, sports cars and designer dresses, the high price of an elite education may make it only more coveted. As Hanlon has acknowledged, it’s not as though Dartmouth is about to run out of potential customers. “People will come because Dartmouth is Dartmouth,” he says. “It is the environment that we create here that attracts students and faculty and will continue to.”

Dartmouth’s endowment does cover a hefty 20 percent of College operations. At schools with larger endowments such as Harvard, Yale and Princeton, endowment funds cover more than 40 percent of operations.

But Hanlon could hardly be called tone-deaf on the issue of rising tuition. Last spring, in an unusual move, he created a mini-course focused on the budget at Dartmouth, pulling back the curtain a bit on a notably opaque process. (Many of the numbers cited here are drawn from that course, as well as from a range of independent and federal agencies’ reports, not all of which use the same computations.) Despite a topic that might seem unpalatably dry, the noncredit course, held on weeknights, filled up in a single day with faculty, students and staff, according to instructors, who included Rick Mills, the College’s executive vice president and chief financial officer, and Mike Wagner, vice president for finance. Throughout, they were peppered with so many questions that five classes were not enough to cover all the course material.

Another budget course is being offered this spring, in which Hanlon may share what he told DAM: “The budget is a tool to drive academic excellence. It is not an end in itself.” His bottom line, however, is that “you have to spend to innovate.”

Where the Money Goes

The College spent about $982 million in fiscal year (FY) 2014 on unrestricted revenues of $1.1 billion, according to its most recent audited financial statement.

About 55 percent of that, or $545 million, was spent on what is classified as academics: teachers’ salaries, as well as those of librarians and the custodial staff who take care of classrooms, labs and libraries, plus the cost of maintenance and repair for certain buildings.

Of that $545 million figure, the biggest piece—about $160 million—went to payroll and benefits for faculty, whether tenured, adjunct or visiting, as well as grad-school-level instructors.

Of the College’s employees, slightly more than 1,000—a fourth of the total—are teachers, 60 percent of whom are tenured or on a tenure track. In contrast to Harvard, where the average faculty salary is $161,000, Dartmouth’s average is $118,000, roughly in line with Brown’s, according to the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), a database created by the U.S. Department of Education. Still, some salaries at Tuck, Geisel and Thayer exceed $500,000. Faculty salaries, however, are only one piece of the payroll: $158 million is spent on wages and benefits of other Dartmouth employees who in essence help with the College’s teaching mission: research assistants, lab technicians and administrative assistants in academic departments, as well as football coaches, Hood Museum curators, Dick’s House staff, Hopkins Center jewelry-makers, admissions officers and Rauner librarians.

Then there is $115 million of academic-related spending that includes $15 million in salaries for maintenance workers who operate buildings such as Rollins Chapel, the DOC House and Dick’s House. Many of these custodians, electricians and plumbers are members of the local chapter of the AFL-CIO labor union, which represents 535 College employees. Their compensation is dictated by a contract that runs through this year and allowed for an 8-percent increase during the last three years. This $115 million also pays for oil to heat these buildings, as well as furniture and whiteboards. At $65 million, debt service accounts for another big chunk of this category.

The balance of academic spending, $112 million, was split up, generally speaking, like this: $35 million for equipment and supplies such as stage sets, beakers and fire blankets; $45 million for guest speakers, Hopkins Center and other campus performers—and the ads to promote them—and foreign study programs; $21 million for student and sports team travel and lodging, and $11 million for fellowships and similar non-financial awards, officials explain.

If just 55 percent of Dartmouth’s money is indeed spent on academics, where does the rest—about $437 million—go? For starters, the College spent $128.4 million on financial aid for all students, including those in the graduate schools. Another $127 million went toward sponsored research. Although tens of millions of dollars in grants from private foundations and government agencies such as the National Institutes of Health underwrite much of the cutting-edge work done by faculty with student assistance, the College says it has to kick in to cover the balance.

Included in the list of its financial obligations, Dartmouth spent $97 million in the 2013-14 academic year on what might be thought of as management: $62 million was in the “administrative support” category—the president’s office plus finance, human resources and payroll—with more than half of that total covering wages and benefits for about 1,000 employees. Another $7 million in that category was spent on services provided by lawyers, architects and auditors. And $35 million funded the development office: Most of that is wages and benefits, with hotel rooms and plane tickets accounting for $2 million, according to the College’s most recent financial statement.

“Auxiliaries” round out the College overhead: $84 million was spent on a grab bag of housing—from dorms to Sachem Village in West Lebanon, New Hampshire—as well as the dining halls, Hanover Country Club, Hanover Inn (more on that below), Skiway and, yes, this magazine.

If all of this seems like a heavy lift for a small liberal arts college, it also partly illustrates why Dartmouth needs to charge so much, according to administrators, though they acknowledge that students and their families need relief. “We have reached the point where alarm bells are going off,” Mills says.

C ost Per Student

ost Per Student

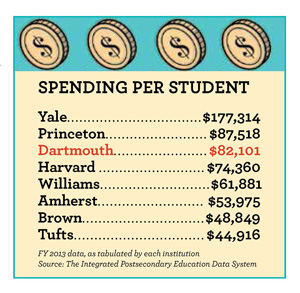

Comparing different schools can be an exercise in futility: Like snowflakes, no two are quite alike, even within the Ivy League, where Dartmouth ranks most expensive behind only Columbia (and 14th most expensive nationally) when looking at tuition plus fees, according to Chronicle of Higher Education data. Still, it can be revealing to contrast Dartmouth’s spending per student—a data point reflective of an institution’s resources that accounts for 10 percent of a U.S. News & World Report ranking—with its peers, using numbers crunched by IPEDS (see chart).

According to IPEDS, the College outlay per student comes to $82,101 per year. That accounts for a long list of expenses that includes teachers, librarians, intramural sports and deans, but it excludes financial aid, which can vary tremendously from student to student. The figure reflects—at least in Dartmouth’s case, given that schools compute their self-reported numbers differently—instructional spending (professors), academic support (tech staff, lab assistants, IT people, libraries, art galleries), student services (support staff, counselors) and institutional support (deans and lawyers). The importance of this metric is debatable, according to Hanlon: “If I were a parent I would evaluate the academic programs at a school. That should be your No. 1 filter.”

Where Revenue Comes From

As a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit, the College is expected to be doing right by the world through education, not trying to drive up revenue. But as enrollment has increased in recent years there’s been a lot more tuition money coming in, which makes up about 30 percent of that $1.1 billion in operating revenue. Dartmouth grew to 6,342 students in 2013-14, from 5,683 in 2003-04, a 12-percent jump fueled primarily by graduate program enrollment. The College collected $320 million in tuition and fees in 2014.

Accepting more students can lead to additional spending on teachers and other services, but when schools increase enrollment, they usually come out ahead, Reich says, although “they still have to maintain the brand” and not lower admission criteria—a concern Hanlon has addressed. “We never want to be lowering our standards to make more money,” he tells DAM.

Accepting more students can lead to additional spending on teachers and other services, but when schools increase enrollment, they usually come out ahead, Reich says, although “they still have to maintain the brand” and not lower admission criteria—a concern Hanlon has addressed. “We never want to be lowering our standards to make more money,” he tells DAM.

Though more graduate students can improve the intellectual climate on campus, Dartmouth could suffer a hard-to-reverse hit if its reputation becomes less than exclusive, Hanlon said during one of those budget lectures a year ago. “Growth [in number of students] has been thought to be a good thing, and that’s not serving higher ed well,” he noted.

Also in 2014, $153 million came in from the broadly named “other operating income” spigot, a miscellany of rents from College-owned real estate, payments to Geisel student psychiatrists, royalties on patents, licensing the Dartmouth name for apparel—even sales of timber from the Second College Grant.

A major revenue stream is the alumni-backed Dartmouth College Fund. Last year DCF and other donors ponied up about $77 million, all of which was channeled into the operating budget along with $21 million released from other gifts. Tens of millions also come in from other sources but go out as if through a revolving door. For instance, sponsored research money from the federal government and foundations, which totaled $178 million in 2014, was restricted for specific studies. Similarly, income “auxiliaries,” or dorm fees of $72 million in 2014, cover room and board.

Financial aid money, that $128 million cited earlier, is basically a wash, analysts say.

Taking Stock

Most significantly, $189 million flowed into College coffers in FY 2014 from its $4.5-billion endowment—that massive, somewhat mysterious stockpile of money the College invests in stocks and real estate. How much of the endowment was tapped for the current fiscal year won’t be known until June.

Since the 1970s, when Iowa’s Grinnell College, under the urging of trustee Warren Buffett, used set-aside funds to invest in a TV station and a startup that turned into Intel, colleges have put their endowments to work. Today, endowment reserves are drawn on sparingly, much as individual investors access their retirement funds. Dartmouth is no exception: It withdraws about 5 percent a year to fund operations, following a rule of thumb in higher education. A little more may be needed in a bad Wall Street year, a little less in a booming one.

Endowments aren’t bulletproof, though. Dartmouth’s lost a staggering $900 million, or 19.6 percent, when the market crashed in FY 2009. But in FY 2014 the endowment, which is divided into a fairly standard 60/40 stock-to-bond ratio, had a banner year, up more than 19 percent, with an annualized return of about 12 percent. While the endowment may be growing nicely, the $4.5 billion Dartmouth has under investment now is next to lowest in the eight-school Ivy League and just No. 22 in overall college endowment rankings, according to the National Association of College and University Business Officers and the Commonfund Institute, an investment firm. Only Brown’s endowment, with $2.9 billion, is smaller. Schools such as Notre Dame ($8 billion) and Washington University in St. Louis ($6.6 billion), for example, are Nos. 12 and 17.

Looked at another way—by endowment per student, a popular measure of an institution’s financial stability—Dartmouth is also behind. That measure can matter, as demonstrated by Princeton and Harvard being able to underwrite more financial aid by drawing on their larger funds. Dartmouth’s endowment breaks down to $710,000 per student, based on current enrollments. Washington University, meanwhile, has $1.05 million per student, and Grinnell, despite finishing at No. 48 in the endowment rankings, claims $1.14 million per student.

Still, even if small compared to its peers, Dartmouth’s endowment does cover a hefty 20 percent of College operations—$208 million budgeted for the 2015-16 school year—vs. 6 percent in 1981, according to Pam Peedin ’89, Tu’98, the College’s chief investment officer. At schools with larger endowments such as Harvard ($35.9 billion), Yale ($23.9 billion) and Princeton ($21 billion), endowment funds cover more than 40 percent of operations, she says.

Growth Patterns

Although spending naturally increased in recent years as the costs of doing business grew, the College has generally broken even. For example, in 2011 total expenses were $853 million on revenues of $865 million, and in 2012 the College spent $892 million on revenues of $899 million. And although expenses in these cases increased 5 percent in a year, revenue went up only 4 percent.

In 2013 Dartmouth spent more than it took in: $960 million, an 8-percent annual jump in costs, according to auditors, while revenues of $957 million were up just 7 percent. That produced a deficit of $3 million, an amount described by analysts as a minor variation common at even financially sound schools. The same year Harvard spent $4.778 billion against unrestricted revenues of $4.771 billion, an operating shortfall. But tapping some restricted gifts—often an option with well-capitalized schools—ultimately enabled Harvard to inch into positive territory.

In FY 2014 the College’s expenses of $982 million were up just 2 percent from the previous year, while revenues, at $1 billion, climbed 5 percent. The College’s balance was positive—about 2 percent of revenues. Even though nonprofits such as Dartmouth are usually loath to ascribe too much significance to profit margins and don’t budget to maximize that cushion, positive margins can reduce Dartmouth’s borrowing costs down the road, so they’re worth pursuing, analysts say.

Hiring seems to drive no small portion of the hike in spending. From 2003 to 2013 the number of faculty swelled by 16 percent, according to official College figures presented in one budget class session. During the same period the number of grad students went up by 30 percent, the data show, but the undergrad population climbed just 4 percent.

Staff levels, meanwhile, appear to have climbed about 4.5 percent from 2003 to 2013, according to College data. Although this may not appear excessive on its face, viewed across a longer span of time, the College can seem to be piling on non-teaching employees, who, as noted, make about 75 percent of its total payroll.

Since 1987 Dartmouth’s full-time professional staff has swelled by 324 percent, according to a recent study from the New England Center for Investigative Reporting. Although reflective of a national trend, the College’s number of administrators—the kind of employees likely to be found in deans’ offices—has swelled by almost 80 percent. This far outstrips the pace of both enrollment growth and staffing increases at schools with which it competes. The study revealed that the number of non-academic employees has more than doubled at colleges and universities nationwide during the past 25 years.

At Brown, the figures were 289 percent growth for staff and 73 percent for administrators; at Harvard, 120 percent staff and 74 percent administrators; and at Williams, 137 percent staff and 131 percent administrators. (Princeton administrators actually dipped 78 percent, the data show, but a Princeton spokesman declined to respond to a request for comment about the accuracy of the data.)

At Dartmouth certain kinds of staff jobs seem to account for most of the growth. In a single year, from 2012 to 2013, the number of vaguely labeled “administrators” climbed from 623 to 644, a 3-percent increase, according to College statistics. Dartmouth officials did not respond to requests to spell out the exact job titles that fall under this heading. Likewise, the number of people in “financial operations occupations” went up from 160 to 173, or 8 percent, and the number of those who work in “academic affairs”—the provost’s office, namely—jumped from 232 to 257, or about 11 percent.

Taken together, critics say, the payroll figures suggest the College suffers from managerial bloat. “At the very top there is always a tendency for bureaucracies to replicate themselves, because everybody wants to have an assistant,” Reich says. “But if everybody gets to have an assistant, there will be assistants to the assistants.”

And it’s not just the number of new employees that spending watchdogs worry about, but the size of their non-faculty salaries too.

Dartmouth officials say they are compelled to create dozens of positions to comply with federal regulations, to which the College is subjected as a recipient of federal Pell grants and other government funding. These laws include Title IX, the 1970s act barring gender discrimination, as well as the 1990 Clery Act, which takes aim at campus crime, including sexual violence, both of which require periodic reports to federal authorities. Last year, for instance, the College hired its first-ever Title IX and Clery compliance officer. Costly new crime-tracking software systems have also been put in place, officials say.

Even sports teams have to comply with increasingly strict NCAA regulations ranging from employee certification in emergency medical services to increased reporting. Mills, the College’s CFO, says most of these changes create an improved quality of life, though they do come at a cost. “There was no ill intention in any of these rules [imposed by the federal government to protect students] and prima facie they are reasonable goals,” to make the campus more inclusive and safer, Mills says, but their tracking and reporting requirements hike costs by “millions and millions of dollars.”

Changes proposed last winter under Moving Dartmouth Forward will likely further inflate expenses. Hanlon has called for security and bartenders at fraternity parties, annual surveys about sexual assaults (at an estimated $85,000 per year) and social programming that will be an element of Dartmouth’s new living-and-learning housing system, for example.

Filing taxreturns has also become more involved and onerous through the years, officials point out: Dartmouth’s Form 990, the tax document filed by not-for-profits, was 27 pages in 2003, but 84 in 2013. Employment and healthcare laws have also required extra paperwork, while the surge in applications to the College—they’ve more than doubled in a decade—has forced the admissions department to beef up its staff to read them all.

There’s also the argument that professors who carry a light course load, as they do at Dartmouth, provide “a smaller bang for the buck than teachers at other schools, who tackle several sections at a time,” says Bill Hall, the chief financial officer for Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island, who has worked in higher education for decades. His far-less-funded school “couldn’t survive if our guys were teaching one class a semester,” Hall says. Even some Dartmouth professors, who did not want to give their names out of worries about reprisals, agreed with Hall’s assessment: Dartmouth profs, who don’t typically utilize teaching assistants, don’t teach as many courses as profs do at many other schools. In Hanover, profs typically teach three or four courses a year; at schools such as Salve Regina it is double that.

Building Boom

Anybody who has not set foot in Hanover in a few decades might be surprised how many more buildings there are: the result of an ambitious plan to expand the campus with more classrooms, dorms and arts facilities.

All told, the building space on the 265-acre main campus increased by almost 20 percent from 2003 to 2013, from 4.1 million to 5 million square feet, school records show. The reason is, quite simply, that Dartmouth must keep up with the rest of the Ivy League, according to Mills. If one campus puts in a climbing wall, others will likely feel compelled to follow suit. This rivalry is also being fueled by a desire to improve college rankings, which play a huge role in where students end up, even as many administrators condemn them as superficial.

Personal generosity has alleviated some of the building boom’s impact. The Black Family Visual Arts Center, for example, which opened in 2012, cost $72 million, but private equity executive Leon Black ’73 donated $48 million of his own fortune to the state-of-the-art facility. Some development plans were put on hold during the recession, such as the $12-million project to replace the seating area on the west side of Memorial Field, but have been revived.

Then again, some projects have dragged on for years and had huge overruns. The two-and-a-half-year renovation of the Hanover Inn, for instance, was initially slated to cost $13 million and “require no new operating funds from the College, as financing for the project will be supported by existing funds and future revenue growth from the inn,” according to a 2010 press release. But the hotel’s final price tag ballooned to $42 million, a difference of $29 million that appears to have been shouldered solely by Dartmouth.

In FY 2013, according to its most recent Form 990, the College paid $90 million to contractors. The top recipient was Engelberth Construction of Keene, New Hampshire, which was involved with the renovation of Collis and several other campus projects. It was paid $33 million.

Installing the latest technology also is expensive. Even though the price of the hardware has dropped tremendously in recent decades, Dartmouth has to pay staff to make its systems secure and run smoothly, Wagner says. “We’re also always trying to implement changes to help faculty use technology in their teaching,” he adds.

Dartmouth officials are quick to disabuse critics of the notion that doing business in rural New Hampshire means that basic goods and services cost less than they would in a city. “At first blush, you would think things would be cheaper up here,” says Mills, who was previously employed by Harvard. “But there’s a scarcity. Many test tubes, for instance, need to be shipped from Boston, which adds to their cost. Similarly, to have a plumber around who can respond quickly to emergencies, Dartmouth has had to put some on staff. It would be far too risky to rely on freelancers.”

What To Do?

Although the total price for four years in Hanover was ostensibly $248,000 in FY 2014, the average student has paid about $135,000, after factoring in financial aid awarded by the College and other outside stipends the College does not tabulate.

Similarly, tuition can be understood to have risen less than half as much in the last 20 years as official government data would suggest, according to a 2014 New York Times study. Although the list prices of Dartmouth and other schools have spiked, the report says, they have been offset by grants and financial aid that have kept actual student cost constant even while driving overhead up. Even so, Dartmouth’s aid-reduced tuition can be considered steep and financially out of reach for many students—and there is no guarantee that students paying full tuition can continue to adequately offset those in need of aid.

So, what to do? It may help that for this academic year—and the next—Dartmouth’s tuition has been raised by just 2.9 percent, the lowest hikes since the late 1970s. For the 2015-16 academic year, tuition, room and board, and fees will total $63,744, but trustees have also approved an almost 7-percent increase in spending on financial aid.

If Dartmouth were a for-profit corporation, the path to cost reduction could involve layoffs, but the College has shown little appetite for broad cuts. Hanlon has said he thinks the growth in costs stems in part from the College adding new programs without eliminating old, redundant ones. Last fall he told each of the College’s schools, including the undergraduate arts and sciences department, that it needs to cut 1.5 percent from its budget each year and redeploy it elsewhere to trim waste—poorly attended foreign study programs, for instance—and spur innovation. Even though some critics say that type of reorganization doesn’t sufficiently address excess spending, College officials defend the move as a key first step, and Hanlon’s approach has attracted positive attention from some media outlets and higher ed analysts. “The new environment is to think more substitutionally than additively,” Mills says.

The impact of employee benefits packages remains to be seen. Although critics of the College’s budgetary policies, such as Dartblog’s Joe Asch ’79, have complained that employee packages are too generous, the College shrank its contributions to employee retirement programs in 2008 and eliminated a retirement healthcare subsidy for those hired after 2009. Indeed, the share of healthcare premiums employees kick in now is about 31 percent, according to College figures, up from 24 percent in FY 2009. Similarly, for employees aged 35 to 39, for example, the College now chips in 7 percent of total salary as a retirement benefit, down from 10 percent, the data show—generous, but hardly out of line with competing New Hampshire employers. Many University of New Hampshire employees pay only 16 percent of their healthcare premiums and UNH has a standard retirement account contribution level of 10 percent against a 6-percent employee contribution.

Some have suggested making Geisel, which posted a $5.5 million deficit in FY 2014, a stand-alone entity, but Hanlon, at least, is opposed. “I think it adds tremendous value to any university to have a medical school when more than 15 percent of the GDP is spent on healthcare,” he says. “It’s an area where we’ve seen some of the most awesome advances over the last century.”

Even more startling has been the idea to freeze tuition, so it wouldn’t climb any higher from year to year. Mills and Hanlon dismiss that idea. “Freezing tuition has the feel of a more PR-oriented move. It’s just unrealistic to think about keeping tuition frozen for a decade,” Mills says. “I prefer something less gimmicky and more sustainable,” says Hanlon. “I’m a long-term thinker. I want to put in mechanisms over time that move us to a great place.”

In all their calculations, College officials seem to be counting on a continued demand for the product they’re selling. Those budget lectures last year pointed out that in the mid-1960s a person with a high-school diploma made about 81 percent of what a person with a college diploma earned. Today, though, that high-school graduate may make only 62 percent of the comparable college alum.

“We want people to say, ‘The premium you get from attending college, and especially at Dartmouth, is still worth it,’ ” Wagner says. “And it’s not just about making a great salary.” Still, spending “has to slow,” Mills says. “That message has been received loud and clear.”

C.J. Hughes, a regular contributor to DAM, lives in New York City.