Number 191. How sweet it is.

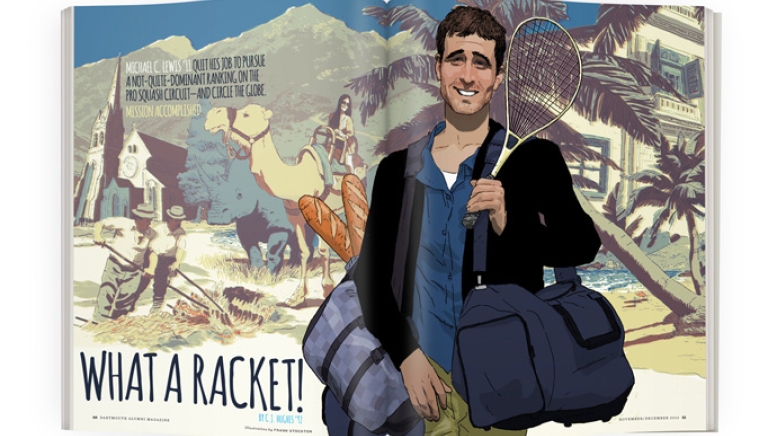

Well, maybe not for everybody, but for Michael C. Lewis, a venture capitalist turned pro squash player, the ranking validates his decision to quit his job more than a year ago and embark on a long, strange trip around the world and into the realm of international squash.

Lewis, 27, always wanted to crack the list of the top 200 squash players worldwide. This summer, after dozens of matches and countries, he finally did it, caroming from No. 289, when he began the pro circuit in May 2014, to No. 191 in September.

“Everybody has something they want to go and do, and if you start down that path it’s incredible what can happen,” Lewis says. “I just had to take that first step.”

Still, mastering drop shots and drives was only part of the plan. Like scores of backpacking post-college 20-somethings before him, Lewis wanted to see the world. A racket sport, he realized, could be his ticket.

Unlike rivals such as No. 1-ranked Mohamed Elshorbagy of Egypt or No. 2-ranked Nick Matthew of Britain, Lewis doesn’t catch flights home after matches to resume training but instead stretches visits into multi-day jaunts. His former corporate grind with Bain Capital Ventures has been replaced by the every-day-must-be-savored rhythms of la dolce vita: Beaches. Discos. Hikes. A rhino preserve. A ride on a camel. A Chilean country fair. An Argentinean sangria-soaked rib roast.

“He’s meeting new people, staying extra weeks and getting to do some really, really cool stuff,” says Chris Hanson ’13, a squash teammate of Lewis’ in college and a fellow pro player today. Hanson—whose No. 85 rank among more than 500 players makes him the third-best American in a sport whose top competitors hail from England, Egypt and Pakistan—considers Lewis’ level of leisure time very impressive. “If you have an extra couple days at these tournaments, you might see a few things here and there,” Hanson says. “Mike is taking it to the next level.”

Lewis’ one-man, two-bag tour has been heavily dependent on the kindness of strangers, who have offered meals, rides and beds along the way.

In fact, in the 15 months Lewis has been on the road since May 2014, when the first leg of his journey took him to Auckland, New Zealand, he estimates he’s spent just one night alone, in a hotel in France, when an early-morning flight required it.

And that’s saying a lot. As of early September, Lewis had hit about 50 countries and territories, including South Korea, Wales, Malaysia, Brazil, Zambia and Zimbabwe—a lot of geography in which to scrounge up places to crash.

“I’m constantly amazed by the people who have opened up their worlds to me and ushered me into their lives,” says Lewis, whose measured cadence can recall a business pitch, though his sincerity is hard to doubt.

“I’ve learned how powerful the human connection is,” he says in a phone interview from Klaipeda, Lithuania, where he was on his way to an electronic music festival with friends met along the way after teaching a squash clinic.

Indeed, paid accommodations make up only about a quarter of the lodging Lewis needs, and tournament hosts often pick up those tabs. Complimentary beds, inflatable mattresses and couches, arranged through social media and a daisy chain of connections, take care of the rest.

A “friend of a friend of a friend of my cousin” came in handy in Asunción, Paraguay, for instance, says Lewis. And in Latvia it was Ieva, the daughter of “a close friend of my friend Catherine’s Latvian-American friend from college Erika’s cousin’s parents,” he wrote at Couch Surfing the Tour, the blog wherein he chronicles his adventures. It sometimes reads like a foodie travelogue as he eats, drinks and dances his way across time zones.

“Baguettes upon baguettes. Bowls of penne. Three types of cheeses: ‘Try! Try!’ Well, I couldn’t be rude. More lettuce. Something called quenelle. I had avoided the Freshman 15 in college but this was the French 15 and there was no way out of it. Oh well,” Lewis wrote of a dinner in southern France.

Freeloading is also made to sound tasty—and fun—as in this account of a ribs-fest outside Rosario, Argentina, last Columbus Day Weekend: “Meat falling off the bone, crispy skin plucked off the cutting board, no forks or napkins, no slowing down. Hands tearing up baguettes in seconds, sangria sloshing in the big pitcher next to a pile of freshly diced tomatoes and lettuce flying out of a communal bowl in the middle. Organized chaos.”

“What makes this whole thing make sense is that Mike loves meeting new people. I know a lot of people say that. But trust me, Mike really lives it.”

Other highlights, not always spelled out on his blog, have been musical, such as a rousing late-night sing-along to Billy Joel’s “Piano Man” in Knysna, South Africa, where Lewis spent last Christmas with friend-of-a-friend Lauren Hodgson, 28, and her family.

“I have a lot of respect for the way he is living his life, getting out there and following what he is passionate about,” Hodgson says. “And he is having such a good time doing it.”

Though women seem to be frequent companions, Lewis won’t say whether he’s been as successful in love as squash. His friends are keeping mum, too.

“He has met a lot of people,” says Tom Mandel ’11, a non-squash-playing fellow Alpha Delta brother who has known Lewis since their first days at Dartmouth, when the outgoing Lewis went knocking on dorm doors to introduce himself to hall-mates.

“What makes this whole thing make sense is that Mike loves meeting new people,” Mandel says. “I know a lot of people say that. But trust me, Mike really lives it.”

Those friends from the road have helped Lewis’ trip pencil out, which has been key: Unless a player is ranked among the top three-dozen or so in the world and can win several of the $5,000 top prizes that major tournaments offer—but which have thus far eluded Lewis—paying one’s way with squash is a quixotic goal, says Hansi Wiens, who coached Lewis at Dartmouth and continues to helm the varsity men’s squad.

“Mike must have saved a lot to have this kind of experience,” says Wiens, a veteran of the global circuit who soared as high as a No. 8 ranking while playing for Germany in 1994. As for his former player’s talents, Wiens is candid: “His movement was not the best, but his concentration and willpower were very, very good.”

Lewis, who was recruited for squash, competed all four years in Hanover and played in the No. 4 spot his senior year, when Dartmouth was ranked in the top 10 nationally.

Although there have been stressful moments—at one point he had a single day to get from Amsterdam to mountain-ringed Andorra, after getting last-minute word of a tournament opening—Lewis is not struggling, thanks to some generous patrons.

Before he shipped off, Lewis lined up donations from members of the tight-knit and well-heeled squash community, such as Doug “Digger” Donahue ’73, managing partner of investment bank Brown Brothers Harriman, who captained the squash team while in Hanover.

Others without a Big Green connection also pledged support, such as Amrit Kanwal, the chief financial officer of MFS Investment Management, a Boston financial firm, who says he chipped in “a couple thousand dollars.”

Over a beer in September 2013 at Boston’s University Club, home to several squash courts, Kanwal advised a serious-minded Lewis to take a break from corporate America and chase his dream. “I told him, ‘You’re thinking too much with your head, and you need to think with your heart.’ ” Kanwal also made a prediction: “ ‘You will be telling stories about this for the rest of your life.’ ”

Lewis’ former employer, Bain Capital Ventures, where Lewis invested in tech firms and kept a map of the world pinned next to his desk, also contributed funds, he says. Such largesse, which is mostly used to cover plane tickets, has been critical. Since embarking on tour, Lewis sheepishly admits he’s won only about $2,000, which underscores how difficult it is to quit a day job and earn a living through squash. “It’s not changing the needle of my own expenses,” Lewis says. But Dunlop, the racket-maker, and Urban Market Bags have also provided equipment, with the expectation that Lewis will sit for some photo shoots with his complimentary products after games.

“He has never asked for anything, and I don’t think he needs it,” says Lewis’ father, Michael M. Lewis, a professor at Tuck and an avid squash player who introduced his son to the sport. “But if he needed me to send a few hundreds dollars to get out of a jam, of course I would.” The son says he’s never even thought of asking.

To Lewis’ relief, jams have been few and far between. One late night in Brazil he felt it would be wise to empty his pockets of money before accompanying a friend into a sketchy bus station, but he’s never felt seriously threatened.

A different risk may be trying to re-enter the workforce after a long absence, a move that was supposed to happen this fall—until an invitation to a prestigious late September tournament in San Francisco motivated him to keep playing. Lewis expects a good finish there to boost his ranking to the No. 150 range, as points are awarded for wins. Participants can ascend quickly in the rankings by entering tournaments with only a few dozen competitors. Plus, he was recently invited to a December tryout for the U.S. men’s national team in Kuwait.

In a sign of his new seriousness, Lewis has gone gluten-free, striking beer, bread and fried food from a diet that used to know few bounds. At the same time he also wants to share his story with anybody who feels imprisoned in a cubicle. In the next few weeks he will launch whentojump.com, a website that will feature inspirational tales on exits from everything from Wall Street to pro baseball. Maine Sen. Angus King ’66, an energy entrepreneur before he ran for governor, will contribute one of them, according to Lewis.

“In a very conservative sense [the traveling] may have cost him [job prospects], because he isn’t gaining any work experience,” Mandel says. “But at any job fair he will be the person with the most captivating story.”

And one that isn’t being taken for granted, says Lewis, reflecting on a dip in the Baltic Sea on that August day in Lithuania: “Every time I get to jump in water I have this quick, intense realization of, ‘How in the world did I get this lucky?’ ”

C.J. Hughes is a freelance journalist based in New York City who writes frequently for DAM and The New York Times.