Last October Agnes “Aggie” Kurtz, founder of Dartmouth women’s sports and the former women’s squash coach, received what seemed like an ordinary e-mail. “You’ve probably seen this,” began the message from Lita Remsen ’82, one of Kurtz’s former players, “but thought I’d pass it on.” Remsen shared an article from that morning’s New York Times about another of Kurtz’s squash protégés, U.S. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand ’88. Kurtz, who has grown accustomed to seeing Gillibrand in the news, hadn’t noticed the article.

Halfway through the story, Kurtz focused. In characterizing Gillibrand’s college days, the reporter described how she and her teammates revered their charismatic coach, and how by instilling in her players the importance of discipline and teamwork, Kurtz had shaped a collection of non-squash recruits into one of the country’s best squads. “She was a strong woman,” the senator said, “who understood the importance of athletics in developing women.”

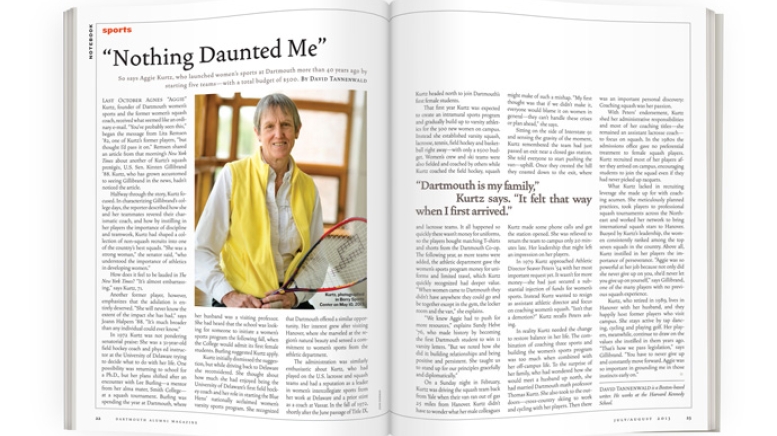

How does it feel to be lauded in The New York Times? “It’s almost embarrassing,” says Kurtz, 71.

Another former player, however, emphasizes that the adulation is entirely deserved. “She will never know the extent of the impact she has had,” says Joann Halpern ’88. “It’s much broader than any individual could ever know.”

In 1972 Kurtz was not pondering senatorial praise: She was a 31-year-old field hockey coach and phys ed instructor at the University of Delaware trying to decide what to do with her life. One possibility was returning to school for a Ph.D., but her plans shifted after an encounter with Lee Burling—a mentor from her alma mater, Smith College—at a squash tournament. Burling was spending the year at Dartmouth, where her husband was a visiting professor. She had heard that the school was looking for someone to initiate a women’s sports program the following fall, when the College would admit its first female students. Burling suggested Kurtz apply.

Kurtz initially dismissed the suggestion, but while driving back to Delaware she reconsidered. She thought about how much she had enjoyed being the University of Delaware’s first field hockey coach and her role in starting the Blue Hens’ nationally acclaimed women’s varsity sports program. She recognized that Dartmouth offered a similar opportunity. Her interest grew after visiting Hanover, where she marveled at the region’s natural beauty and sensed a commitment to women’s sports from the athletic department.

The administration was similarly enthusiastic about Kurtz, who had played on the U.S. lacrosse and squash teams and had a reputation as a leader in women’s intercollegiate sports from her work at Delaware and a prior stint as a coach at Vassar. In the fall of 1972, shortly after the June passage of Title IX, Kurtz headed north to join Dartmouth’s first female students.

That first year Kurtz was expected to create an intramural sports program and gradually build up to varsity athletics for the 300 new women on campus. Instead she established varsity squash, lacrosse, tennis, field hockey and basketball right away—with only a $500 budget. Women’s crew and ski teams were also fielded and coached by others while Kurtz coached the field hockey, squash and lacrosse teams. It all happened so quickly there wasn’t money for uniforms, so the players bought matching T-shirts and shorts from the Dartmouth Co-op. The following year, as more teams were added, the athletic department gave the women’s sports program money for uniforms and limited travel, which Kurtz quickly recognized had deeper value. “When women came to Dartmouth they didn’t have anywhere they could go and be together except in the gym, the locker room and the van,” she explains.

“We knew Aggie had to push for more resources,” explains Sandy Helve ’76, who made history by becoming the first Dartmouth student to win 11 varsity letters. “But we noted how she did it: building relationships and being positive and persistent. She taught us to stand up for our principles gracefully and diplomatically.”

On a Sunday night in February, Kurtz was driving the squash team back from Yale when their van ran out of gas 25 miles from Hanover. Kurtz didn’t have to wonder what her male colleagues might make of such a mishap. “My first thought was that if we didn’t make it, everyone would blame it on women in general—they can’t handle these crises or plan ahead,” she says.

Sitting on the side of Interstate 91 and sensing the gravity of the moment, Kurtz remembered the team had just passed an exit near a closed gas station. She told everyone to start pushing the van—uphill. Once they crested the hill they coasted down to the exit, where Kurtz made some phone calls and got the station opened. She was relieved to return the team to campus only 20 minutes late. Her leadership that night left an impression on her players.

In 1979 Kurtz approached Athletic Director Seaver Peters ’54 with her most important request yet. It wasn’t for more money—she had just secured a substantial injection of funds for women’s sports. Instead Kurtz wanted to resign as assistant athletic director and focus on coaching women’s squash. “Isn’t that a demotion?” Kurtz recalls Peters asking.

In reality Kurtz needed the change to restore balance in her life. The combination of coaching three sports and building the women’s sports program was too much when combined with her off-campus life. To the surprise of her family, who had wondered how she would meet a husband up north, she had married Dartmouth math professor Thomas Kurtz. She also took to the outdoors—cross-country skiing to work and cycling with her players. Then there was an important personal discovery: Coaching squash was her passion.

With Peters’ endorsement, Kurtz shed her administrative responsibilities and most of her coaching titles—she remained an assistant lacrosse coach—to focus on squash. In the 1980s the admissions office gave no preferential treatment to female squash players. Kurtz recruited most of her players after they arrived on campus, encouraging students to join the squad even if they had never picked up racquets.

What Kurtz lacked in recruiting leverage she made up for with coaching acumen. She meticulously planned practices, took players to professional squash tournaments across the Northeast and worked her network to bring international squash stars to Hanover. Buoyed by Kurtz’s leadership, the women consistently ranked among the top seven squads in the country. Above all, Kurtz instilled in her players the importance of perseverance. “Aggie was so powerful at her job because not only did she never give up on you, she’d never let you give up on yourself,” says Gillibrand, one of the many players with no previous squash experience.

Kurtz, who retired in 1989, lives in Hanover with her husband, and they happily host former players who visit campus. She stays active by tap dancing, cycling and playing golf. Her players, meanwhile, continue to draw on the values she instilled in them years ago. “That’s how we pass legislation,” says Gillibrand. “You have to never give up and constantly move forward. Aggie was so important in grounding me in those instincts early on.”

David Tannenwald is a Boston-based writer. He works at the Harvard Kennedy School.