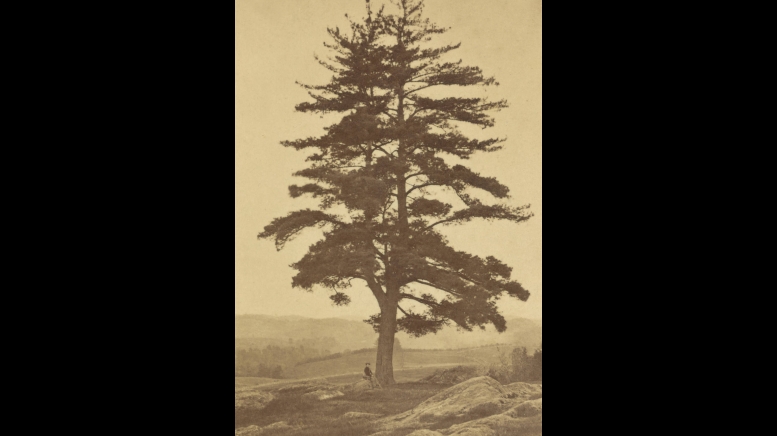

1896—The “Old Pine,” judged from its carefully and independently counted 112 rings, may be safely assigned, according to the best arboriculturists, to within a year or two of 1785, for its origin.

Jacob Gale, class of 1833, is the earliest alumnus to report as current in his college days, a vague legend of three Indians singing about a tree their farewell song, beginning, “When shall we three meet again….”

The earliest reminiscence of the Old Pine is from Jas. F. Joy, class of 1833, who writes: “The ‘Old Pine’ was standing of course in my day, and there were stories current then about some class which graduated just before I entered college gathering about that tree and singing ‘Auld Lang Syne’ before parting.” Such stories might naturally have grown into the Indian legend.

In the 1840s the Old Pine had become more generally known, and from this time on it tells its story not by legend but by personal reminiscences of alumni. An alumnus of 1840 says: “Some of us would occasionally, when out for recreation, sing the hymn which tradition told us the three Indians composed and sang.” A graduate of 1845 writes: “We, like all other classes, had many meetings around the Old Pine for gossiping, storytelling, and music and some other exercises.” One of these “other exercises” was the tarring and feathering of a man charged with crime. “The class of 1844 at the time of its graduation held memorial services around it and smoked the pipe of peace,” writes the Rev. Thos. Wilson, class of 1844. Yet four other members of 1844 state the class had no exercises. One remembers none, another gives probably the true conclusion: “Perhaps some who were smokers did as Mr. Wilson remembers.”

From 1854 until 1895, with the exception of 1855 and a few years when Class Day was omitted on account of quarrels over class elections, the Old Pine witnessed Class Day celebrations consisting of singing, an address, smoking the pipe of peace, sometimes from a single pipe passed around, sometimes from long clay pipes….The scrimmage for the wreath of flowers is reported in vogue as early as 1854 and as late as 1870, after which it was replaced by the ceremony of breaking the pipes against the tree at a given signal, followed by a rush for mementoes. This custom was continued until 1893.

July 29, 1887, the Old Pine was struck by lightning, and on June 14, 1892, its main branch was broken by a whirlwind. As if it were an old friend, the word passed around among alumni “the Old Pine is dying.” Its friends tried to save it in 1894, but, in spite of the greatest care, it failed to replace its brown needles with green ones in the following spring. After witnessing its last Class Day, it was cut down July 23 and 24, 1895. A shot was found in the seventy-ninth ring from the outside. The total height was seventy-one feet. The stump, four feet high, is left standing and has been treated with a preservative.

Its legends, its associations, its age, its commanding view, its dreamy rustling overhead made the Old Pine the poetic and imaginative spot in college life for more than half a century. Much generous sentiment has clustered about it and been said and sung by undergraduate and alumnus.

More than sixty generations of college classes who have venerated it will find their veneration voiced in these spontaneous words of genuine reverence by Dr. John Ordronaux of the class of 1850: “I have known it since 1846 and never approached its hoary presence without a feeling of reverence, for I recognized in it a member of the ancient nobility of Pines, the sentinel tribe of our Northern Forests. Had I been one of the ‘genus veritabile vatum,’ I should long since have made it speak in verse like Tennyson’s Talking Oak, and surely it would tell of many pleasant unwritten chapters in the Epic of College Life.”

Adapted from “Historical Sketch of the ‘Old Pine’ ” by Foster, a history professor, and Jesup, a botany professor

Arbor Vitae

“Let us take a backward glimpse, for a moment, with the spirit of the Old Pine. Towering above its companions on this eminence, for nearly a century it greeted first the rising sun and was the last to catch its declining rays. Over this pleasant valley it watched by day and sighed its gentle song with the night breezes. Its stately form, so it is said, sheltered the solemn parting of three Indian chiefs. To it the early residents must have turned as to a beacon light. And I like to think of the strength and cheer which this valiant monarch of the forest has contributed to the hundreds of Dartmouth men who came to look upon it with reverence.”

—Arthur Ward Gilbert ’21

Class Day address on June 18, 1921

Photo courtesy Dartmouth College Library