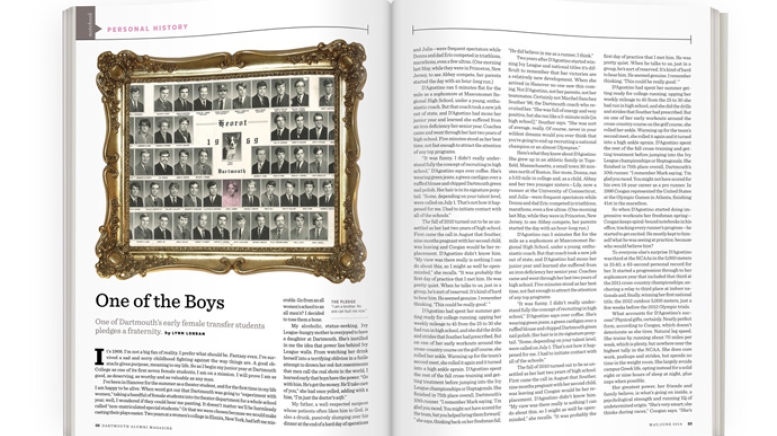

It’s 1968. I’m not a big fan of reality. I prefer what should be. Fantasy even. I’ve survived a sad and sorry childhood fighting against the way things are. A good obstacle gives purpose, meaning to my life. So as I begin my junior year at Dartmouth College as one of its first seven female students, I am on a mission. I will prove I am as good, as deserving, as worthy and as valuable as any man.

I’ve been in Hanover for the summer as a theater student, and for the first time in my life I am happy to be alive. When word got out that Dartmouth was going to “experiment with women,” taking a handful of female students into its theater department for a whole school year, well, I wondered if they could hear me panting. It doesn’t matter we’ll be harmlessly called “non-matriculated special students.” Or that we were chosen because we would make casting their plays easier. Two years at a women’s college in Elmira, New York, had left me miserable. Go from an all women’s school to an all men’s? I decided to toss them a bone.

My alcoholic, status-seeking, Ivy League-hungry mother is overjoyed to have a daughter at Dartmouth. She’s instilled in me the idea that power lies behind Ivy League walls. From watching her drink herself into a terrifying oblivion in a futile attempt to drown her red-hot resentments that men call the real shots in the world, I learned early that boys have the power. “Go with him. He’s got the money. He’ll take care of you,” she had once yelled, adding with a hiss, “I’m just the doctor’s wife.”

My father, a well-respected surgeon whose patients often liken him to God, is also a drunk, passively slumping over his dinner at the end of a hard day of operations and office hours. But he does life-or-death things. He makes more important decisions than whether to send the blue or the black dress back to Saks. No. It’s clear to me. Men have choices. Men get respect. And I can’t wait to be one of them.

When I realize most men on campus are in fraternities, I join one. Chi Phi Heorot is just down the street from my two-room apartment. I venture in one night to introduce myself to a longtime friend of a friend. It’s pledge night. The house bustles with eager underclassmen desperate for acceptance into a higher male order. The only women there are pretty, smiling girlfriends helping with name tags, hoping to make the house more enticing. I feel superior. It’s a new feeling. Though I am probably being checked out more for the way my white cashmere sweater clings to my breasts, I am oblivious. I tell anyone who does not know it that women are on campus now—and not as decoration.

Whether it is my idea, someone else’s or a mutual “ah ha!” I don’t remember, but by the time the night ends I am a pledge. Or, in Heorot vernacular, “shitbird.” I report as ordered every day, ready to do whatever I am told. I kneel at the bottom of the spiral staircase, reciting nonsensical bullshit while older brothers dump water, beer and whatever other liquid they can find to soak me. The absurd amount of male attention is heady. The fact I can take it like the guys makes me high. And when initiation comes, I’m ready.

Beer-soaked, puke-layered basement. Keg looming large. Foam spilling to the floor. I take a 3:15 position on “the pledge clock.” Chug a beer. Walk. Chug a beer. Walk. I hate beer. It reminds me of unbaked bread and male excitement at baseball games. Gulping, belching, I keep up. I have to. I am drinking for all women everywhere. Forget this is the dumbest thing asked of me since my mother said I have to be a virgin when I marry.

I follow a high-flying flock of shitbirds into the rancid bathroom to smoke fat, foul cigars. Nauseated and drunk, I traverse the obstacle course. Coatless and freezing, I stumble down the snowy hill. Blindfolded and led into some inner room, I kneel and stick out my tongue. An Alka Seltzer burns a hole. Someone helps me up as I hear a deep and foreboding voice: “Are you ready for the secret of the sacred chi?”

“Yes,” I say. “But if you do anything different for me because I’m a girl, I’m going to be really, really mad!” The blindfold is removed and, as my eyes adjust to the candlelit room, I see a casket. It opens in front of me. Empty. I cry out, outraged some secret is being withheld, when J.B., a stocky, hairy brother standing high on a windowsill like a Caucasian King Kong, pushes back the heavy brocade curtains to reveal himself, stark naked. Everyone laughs. And I am a brother. No one can hurt me now.

I pass out and miss the dinner.

As I gain ground in a world of men, back home my mother’s alcoholism progresses. I direct and win the best play award in the inter-fraternity play contest as my 44-year-old mother grows increasingly jaundiced, her liver failing, her brain getting wet. I hold fast in the safety of family denial. There’s no time anyway. I am too busy being a good Dartmouth man.

I’m also busy ending the Vietnam War. At 17 I’ve already marched on the Pentagon and been tear-gassed. A small badge of honor I wear with outsized pride. The lies of the war infuriate me, and I want ROTC off Dartmouth’s campus—now. I light candles at vigils, fast and boycott classes during the spring strike. I self-destructively decline the big acting role I’ve been longing for all year in favor of this higher cause. Then comes Parkhurst.

Adrenaline shoots through my body as I help take over the administration building, toppling tyranny itself. This abused and mixed-up child of two alcoholics screams out, “You have to stop what you’re doing!” Behind locked and furniture-blocked doors, I wait until demands are met. Hours pass. Someone phones in an order for fried chicken. Dartmouth plans its course of action. Hours pass. Night falls dark and dangerous. Dartmouth runs out of patience. It wants its building back.

Someone helps me to an open window. Black, riot-geared, helmet-heavy, baton-wielding, scary-as-hell state troopers line up below. I join in with Nazi-like intensity: “Pigs! Pigs! Pigs!” The men in uniform, ready to do battle, don’t look human. And then the proverbial time comes to separate the men from the boys. I sit on the floor, scared out of mind and body. My survival self knows jail will be my undoing.

Coming to Dartmouth has been my escape from my familial jail. A shot at freedom. Sitting on the cold floor of Parkhurst I know I will not survive a cell with real bars and a lock I don’t have a key to. I cry like a girl as I am carefully helped by friends out a back window like an 18th-century woman over a cloaked rain puddle, avoiding arrest.

As the year ends I am desperate not to be shipped back to Elmira. Though my mission may have been misguided, every ounce of me wants to stay and get my Dartmouth degree. I see absolutely no reason why I can’t. At a meeting of the trustees held at the top of Hopkins Center to discuss coeducation, I breathlessly stand before a microphone and beg those in power to allow transfer students to formally enroll in the College. I ask in all earnestness and with the naiveté of a still-teenager: “But what’s wrong with us? You marry us!” I tell them. Everyone laughs. Am I not just the prettiest and most clever girl?

Days after my plea I call home to learn my mother is dying. No one had bothered to tell me. I run crying to Heorot. My fraternity brother and ex-boyfriend stops studying for his final exams and lovingly drives me to New Jersey. My mother dies two weeks later from complications of alcoholism. Although I return to Hanover in August I am too emotionally distraught to take my finals. That summer trustee Tom Braden ’40 sends me a letter that praises me for the courage I had demonstrated at the board meeting at the Top of the Hop. “It is unfortunate the sowers of the seeds of revolution are not always able to reap its benefits,” he writes. It’s nice, but there’s no consoling me. My mother had lost her battle and so had I—to an institution not yet ready for women. Even one pretending to be a man.

Lynn Lobban is a singer, actress and writer who lives in Santa Monica, California. This is excerpted from her memoir-in-progress, Shitbird.