When the secretary of the jury for the 2008 Nobel Prize for Literature last fall dismissed American literature as too “insulated and isolated” and claimed that the United States does not participate in the “big dialogue of literature” because it doesn’t translate enough, American editors and writers were up in arms to defend American literature and praise the United States as a multicultural society.

Margaret Williamson, professor of classics and comparative literature, however, concedes the secretary may have been on to something: “I think it is the case that there is not enough translation done and not enough awareness of what translation is,” she says. She points out that this lack of awareness is inevitable with speakers of any large, dominant language, and reasserts the importance of translation. “No one language expresses all the meanings and points of view in the world,” says Williamson. “Translation is a way of enabling you to get a perspective on the particular way you see the world and the different ways others see the world. And I think that’s important at a personal, cultural and political level.”

When, at the start of last spring’s final class of “Translation: Theory and Practice,” Williamson asks her students to pick a statement that captures the essence of what they have learned, students come up with a variety of aphorisms—philosophical, enigmatic and poetic—that raise questions about the essence of language and communication:

“The whole planet speaks through translation.”

“Translation is a language between languages.”

“Translation is the language of planets and monsters.”

“Nothing is translatable.”

“Everything is translatable.”

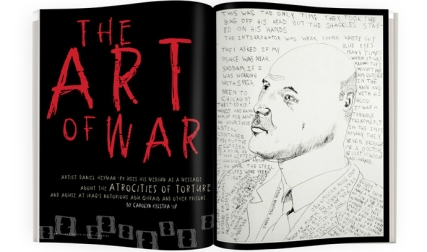

When one student reads the statement, “Contrary to what U.S. military strategy would suggest, Arabic is translatable,” the discussion moves from existential concerns to politics.

“If you come into a country it’s up to you to try to understand the language,” says one student. Another suggests the misperception that Arabic is untranslatable may have contributed to America’s impasse in Iraq, and everyone seems to agree the ability to translate is crucial in reaching intercultural and international understanding. Williamson suggests another statement: “Can we then say that war is the point at which translation ceases?” she asks.

The question reflects the course’s goals of sensitizing students to issues of cultural identity and making them aware that different languages may express different worldviews.

Williamson takes turns teaching “Translation” with its originator, Monika Otter, a professor of medieval English literature who created the course in 2000. Enrollment tends to be high, but Williamson caps the course at 19 so she can spend sufficient time guiding each student. To enroll in the course students must demonstrate at least intermediate proficiency in a foreign language. This means most students are upperclassmen, though one of the students in this class is a freshman who grew up speaking Japanese. The 19 students in the course are comfortable with at least 12 languages: besides Japanese and English students are steeped in ancient Greek, modern Greek, Latin, Italian, French, Spanish, German, Portuguese, Korean and Chinese.

It would be 13 languages if Williamson’s native language were included: She is originally from England, so her native tongue is British English. It’s a source of amusement when she has to ask the students how to translate her British diction into American English, but it is also a serious translation issue. “There is not one English,” says Williamson. Depending on the purpose of the translation, translators need to decide whether to translate into standard British English, standard American English or any other dialect of English. Williamson herself is a classicist, specializing in ancient Greek, so she needs to consult with faculty from other language departments to guide students whose languages she doesn’t know.

As hard as it is to decide into what language to translate a text, it becomes even more difficult when translating across cultures that do not share the same basic concepts, such as ancient Greek and modern English. These are some of the issues students must grapple with. They also discuss the dilemmas that arise when a translator has to make editorial decisions about the word of God (Williamson spends one week of the class on Bible translations) and the question of whether a translator should be faithful to the spirit or the letter of a text.

The poet Galway Kinnell, a guest lecturer, spoke about poetry translation and argued that many poems are mangled by translators who, in an attempt to stay true to the original form, create forced, awkward rhymes. Students must solve such conundrums in their own course assignments, which include the translations of a poem, joke, dialogue and narrative.

The course culminates in a larger translation project that requires the students to write an analysis of the difficulties they faced in the translating and the language choices they have made. The students seem to compete in finding the most demanding and unconventional projects: a letter from Cicero translated into a present-day e-mail, a translation of Virgil into the idiom of a modern novel, and three alternative translations of the Greek philosopher Parmenides—one in metric verse, one in free verse and another in prose. Other challenges include subtitling a video recording of La Traviata in English (with the added difficulty of matching subtitles to the timing of the video frame) and translating the poetry of Ana Merino, who teaches in the Spanish department. The final project of graduate student Tom Wisniewski, Adv’09, a translation from the Italian novel A Strange Day for Alexander Dumas by Rita Charbonier, has led to a contract from Random House.

One of the lessons students take away is that translation is always imperfect. Things that can be said in one language cannot be exactly transferred into another language. “Sometimes saying that something is not translatable is the best gesture you can make toward mutual comprehension,” says Williamson. “Sometimes the gap in understanding is the most important thing to understand.”

When guest lecturer Larry Polansky, from the music department, visits the class, he brings in videos of poetry in a completely different kind of language: American Sign Language (ASL), which he started learning five years ago. The soundless poetry looks almost like a dance. One of the poems describes the stubborn return of dandelions not successfully eradicated as weeds. In one scene the late deaf poet Clayton Valli moves his hands in rhythmic fluidity to show puffballs releasing their seeds. Polansky explains this is a political poem in which the dandelions signify deaf culture, but he declines to give a precise translation: English words can’t convey the visual beauty of ASL poetry, and besides, some members of the deaf community oppose translation into English because they feel it marginalizes ASL.

In this age of globalization the languages of less-powerful communities are under constant threat of being swallowed by more dominant ones. A practical-minded person might say that communication would be much easier if various languages were replaced by a global one, rendering translation unnecessary, but Williamson resists the idea of a universal language. “It would involve a flattening of meaning,” she says. “It would edit out all the particular, all the local.”

Alex Lambrow ’10, a comparative literature major whose final project is a translation of Franz Kafka’s The Trial, says his preoccupation with different languages has given him a more sophisticated perspective on himself. “I now understand that my own language, English, has certain embedded concepts that don’t always fit with concepts in other languages,” he says. “That has made me question the way I think.”

Alison Herdeg ’11, a Spanish and math double-major (“just two different languages,” she says about the seeming disconnect between the subjects), says the course has made her realize that everything is translation, even the communication between speakers of one language. “Every single word I say has all my life’s connotations to it,” she says. “So even if, according to the dictionary, a word has a certain meaning, it has a different connotation for someone else.”

Judith Hertog lives in Norwich, Vermont.