One of Joe Rago’s greatest pleasures in life was staying up all night with his Phi Delta Alpha brothers and then heading to Lou’s for an early morning breakfast. It was a tradition he began as a student and continued as an alum up until his final visit to the iconic Hanover restaurant a few months ago.

Joe was in town for reunion weekend. His waitress that day was Becky Schneider, a woman who’d served him so often through the years that the two of them had become friends. He ordered his regular breakfast of two eggs over easy with dry wheat toast, dousing his food with hot sauce, a condiment he applied as liberally to a greasy breakfast plate as to a fancy dinner of seafood. Before he left, he took Becky’s hand and made her a promise. He said he’d do everything in his power to help her publish the memoir she was working on.

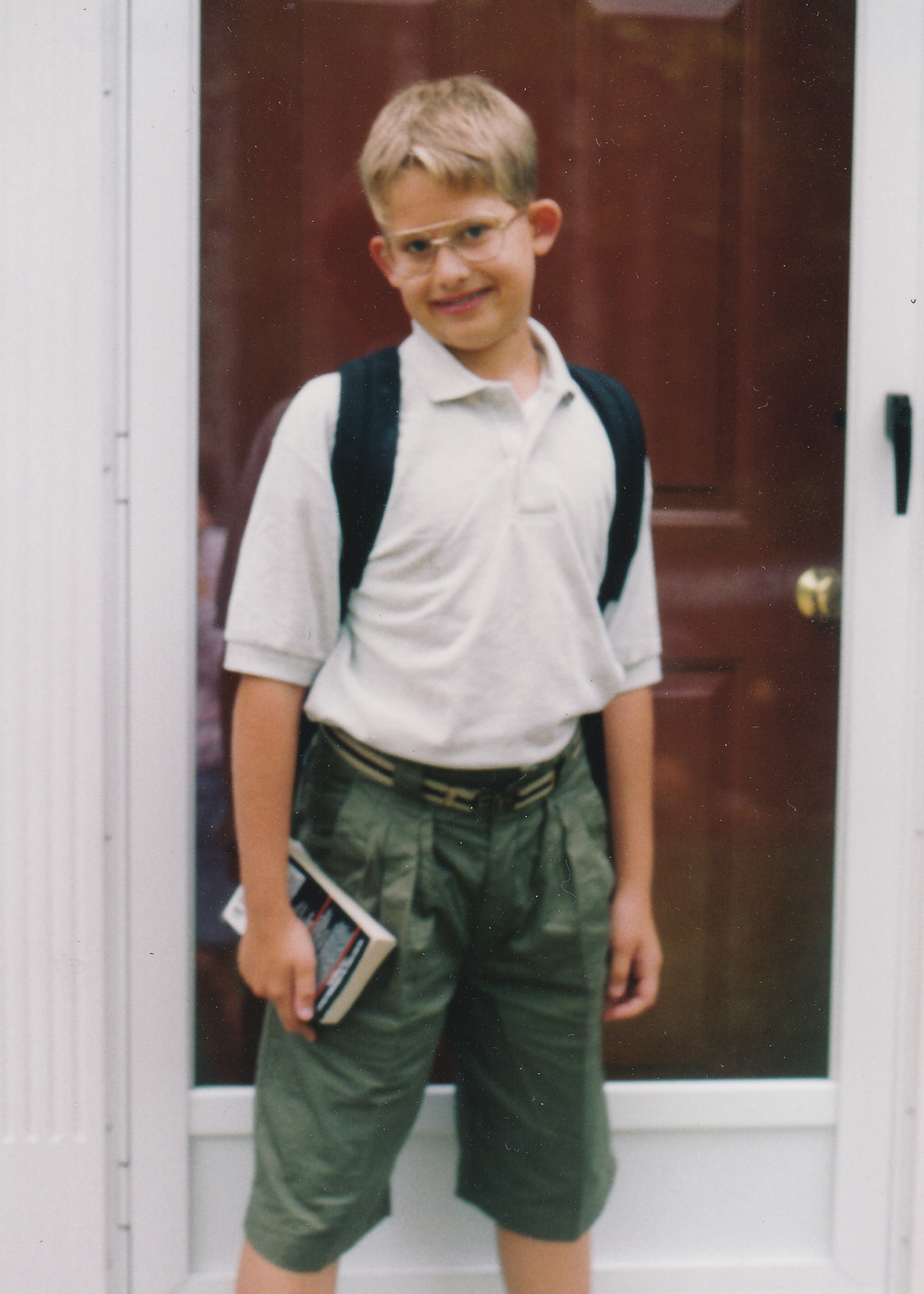

Sixteen years earlier, Joe had come to Hanover as a gangly college freshman. His friends would tease him affectionately for looking like a “baby giraffe” and an “unmade bed.” Now, he was a Pulitzer Prize-winning member of the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal.

The following month, Joe died suddenly and unexpectedly. The cause was a rare inflammatory disease called sarcoidosis, which is fatal in only 5 percent of cases and often goes undiagnosed. No one, not even Joe, knew he had the disease. When he didn’t show up to work on July 20 and was unreachable by phone and email, police were sent to his Manhattan apartment, where they found his body. He was 34.

In the days following his death, it became clear just how many lives Joe touched beyond Becky’s. Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Paul Ryan said, “Joe Rago was a brilliant talent. Gone much too soon. He will be greatly missed.” Yuval Levin, writing online at National Review, commended Joe’s genius, adding: “But he was most extraordinary for his decency. Joe was utterly unpretentious and instinctively considerate.” Roger Kimball, editor of The New Criterion, praised Joe’s “allegro spirit.”

Joe never talked about his relationships with leading figures in American politics and letters. He never talked about his Pulitzer. Downplaying his own talent, he often said he “caught a break” getting into journalism—a statement that reveals his characteristic modesty.

It’s true that luck plays a role in the unfolding of each human life, but Joe was also a preternaturally gifted writer who excelled at almost everything he did from a young age. “I don’t think I even understood how brilliant he was,” says Paul Gigot ’77, Joe’s boss and mentor at the Journal. Few people did. Joe was multifaceted, but he compartmentalized the different parts of his life. His family and childhood, his career at the Journal, his continued involvement with two Dartmouth institutions that profoundly shaped him, Phi Delt and The Dartmouth Review—he kept each of these spheres of his life walled off from one another.

But when those walls come down to reveal the full man, Joe emerges as one who contained multitudes. He was a sardonic writer, but also a thoughtful artist. He was an intense polymath, but also a playful frat boy. He was nostalgic for the past and all things “Old School,” but also found joy in the world as it was. His life was short, but he lived more in less than four decades than most people do across the span of nine. One of his favorite words—appearing frequently in the marginalia of his books—was “hilarious.” His motto: “What’s the point if you’re not going all out?”

Dartmouth changed Joe. It gave him the freedom, his family and friends say, to come into his own in a new way.

Joey, as he was known as a child, was born in 1983 in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where his father, Paul, was finishing up a doctoral degree in natural resources at the University of Michigan. Paul’s work as a fisheries statistician soon took the family to Winchester, Virginia, where Joey spent his early childhood. But it was the family’s next move to Falmouth, Massachusetts, a small town on the southern tip of Cape Cod, that Joe would later call “one of the major influences in my life.” He was 10 years old. “The flinty character of Cape Cod,” he wrote in his college essay, “has shaped my personal growth and evolution”—in particular, its “ethic of common sense and hard work, its demands for a life of independence and clarity, and its aesthetic of simplicity and harmony.” Joe liked saying, with a note of mischief in his voice, that moving to Falmouth rescued him from the “clutches of a Southern upbringing.” He was a New Englander at heart, following in the footsteps of his great-grandfather, Arthur Vose, who was from Milton, Massachusetts, and wrote a book called The White Mountains: Heroes and Hamlets. It was also in Falmouth, at age 10, that Joey asked his parents to start calling him “Joe.”

In Falmouth, Joe’s father worked at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center while his mother, Nancy, took care of Joe and younger siblings Adam and Grace. It was an idyllic childhood. They went to church every Sunday and lived near the ocean. Joe divided his time between school, Boy Scout outings and teasing Grace with nicknames such as “The Face.” “It wasn’t mean-spirited,” she says. “He was loving and supportive.”

Above all, Joe read. His family remembers him always with a book in hand, paging through one after another at a breakneck pace, occasionally lifting his head to contribute some witty line or joke to the family conversation. As a small child he loved the Berenstain Bears books. As he got older, it was the Redwall series by Brian Jacques. In seventh grade he read all of John Grisham’s novels. “As kids we had these science magazines called Zoobooks,” says Joe’s brother, Adam. “I read one. Joe read them all—and catalogued them in his room. In high school he got really into Theodore Roosevelt. But he didn’t read just one book, he read every single book he could find.”

The main thing to understand about Joe, his family and friends say, is that he was intense.

Paul and Nancy knew Joe was talented, but they didn’t think he was an exceptionally gifted child at first. Yes, they started reading to him before he turned 1 and played creatively with him—when Paul traveled for work, he sent young Joey postcards from the road detailing the adventures of an imaginary family of hotel towels—but they never pressured him to achieve and excel. In retrospect, though, his talents emerged early. When he was 3 he became obsessed with dinosaurs and by 4 had learned the names and characteristics of each type—an early indication of his ability to absorb vast amounts of information. When he was 10 his parents realized that he was an innately gifted artist after he painted an ethereal watercolor of the Cape Cod shoreline for Nancy as a Mother’s Day gift. By high school his watercolors were winning statewide awards. So was his independent scientific research about the effects of gravity on germination.

High school was also when Joe began showing a flare for language that would become his signature professional achievement. When his freshman English teacher, Joanne Holcomb, had the students act out some scenes from Romeo and Juliet in class, Joe always wanted to play the part of Mercutio. The quick-witted master of wordplay was one of his favorite literary characters, and Joe performed the role with flourish in front of his classmates—poncho, wooden sword and all: “Consort? What, dost thou make us minstrels?” He loved doing analogy exercises with the class. When he was 16 he asked Holcomb if she thought it was true, per George Orwell, that those who control language control thought.

Like Orwell, who became one of his major influences, Joe was not afraid to challenge received (continued on page 108) wisdom. As editor of the Falmouth High School newspaper, The Intelligencer, he wrote a piece of satire his senior year that criticized the rise of standardized testing. The piece, titled “Mouse Control Assault System”—an Orwellian riff on the name of the state test, Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System—was about mice who were eliminated if they were too weak. Joe resisted the idea that the state could determine someone’s value based on a score.

Joe clearly relished penning polemical articles for public platforms. But in his more private writings, he showed a sensitivity uncommon to a teenager. For an English class his freshman year in high school, the students had to write letters to someone they did not know. This was the late 1990s, and most students wrote to people such as Michael Jordan or the band Nickelback. Joe wrote a letter to Prince William and Prince Harry about the terrible grief they must be feeling after the sudden death of their mother, Princess Diana. He understood their suffering, he said, because he loved his mom so much too.

And sections of his college essay about Cape Cod echo the lyrical poetry of another son of New England, Robert Lowell. The Cape, Joe wrote, “is where the Scotch pines murmur and the soil unfurls a chorale linking residents to all things past and present. It is where the thundering ocean communicates possibility and optimism. It is where lonely, crumbling stone walls, denoting a faded hierarchy, stretch off into the woods obscured beyond sight. In the isolation, the qualities of reverence and veneration for community and continuity are conveyed. The Cape has rooted residents to the past, advocating a respect for history and an admiration for natural beauty.”

When it was time to apply to colleges, Joe set his sights on Yale. In many ways, Yale fit the bill. It was a school for intellectuals and the alma mater of William F. Buckley Jr., who would later become one of Joe’s favorite writers. Joe was waitlisted at Yale, though, and that was a disappointment for a time. So he set off for Hanover—and when he got to campus, Joe fell in love with Dartmouth the way he did with Falmouth. “I can’t imagine being anywhere else,” he wrote in The Dartmouth Review his senior year. Dartmouth, he wrote, was “the greatest school on the face of the earth.”

For Joe, as for many people, college was an opportunity for invention and reinvention. Once on campus he read an essay by H.H. Horne, a late 19th-century Dartmouth professor of English, that mythologized the Dartmouth man as “the vigorous liver of life,” “versatile, straightforward, and capable,” “practical, forceful, and efficient.” For such a man, “the College comes first, partial interests of whatever kind second.” Joe soaked it up. He aspired to Horne’s ideal and, in many ways, became the archetypical Dartmouth man. Dartmouth changed Joe. It gave him the freedom, his family and friends say, to come into his own in a new way.

For one thing, he stopped painting. The break was sudden and absolute. He buried that part of himself so deeply that some of his closest friends and colleagues were shocked to discover, only after he died, that he’d been an artist at all, let alone a gifted one. He also tried his hand at crew after a coach recruited him to the team. Tall yet awkward, Joe was not a natural athlete—yet he nevertheless committed himself wholeheartedly to this new activity his freshman year, coming home from early morning practices with bloody and blistered hands. Another transformation was academic. He arrived at Dartmouth intending to study math and science but decided to major in history, most likely after taking a course his sophomore fall with professor Jere Daniell ’55 on the American Revolution. Joe was quiet in class, but Daniell still remembers Joe’s term paper—about Falmouth during the Revolutionary War—as one of the best he’d seen in his many decades of teaching.

Joe wasn’t merely interested in history, he was infatuated by it. When most college students were nursing hangovers or playing beer pong—and Joe no doubt did his fair share of both—Joe was antiquing in nearby Quechee, Vermont, for Dartmouth artifacts. He didn’t just write a senior thesis about 19th-century Boston intellectuals but devoted his entire junior summer to researching it at the Boston Public Library. He also constantly took pictures, always carrying a disposal camera with him—and, after those became obsolete, a digital one. “He never left Phi Delt,” says close friend Rob Freiman ’05, “without taking a picture of the big elm tree outside its door. He could have made a flipbook.” After Joe died, his family found in Joe’s apartment more than 200 history books about Dartmouth and New Hampshire, a Mason jar full of punch served to him and his Phi Delt brothers on their last night as undergraduates in 2005 and binders holding vintage postcards from those Quechee antique shops.

It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that the same year Joe took Daniell’s class, he got involved with two institutions defined by their devotion to history and tradition: Phi Delt, whose alumni include former General Electric CEO Jeff Immelt ’78 and Game of Thrones co-creator David Benioff ’92, and The Dartmouth Review, where Laura Ingraham ’85 and Dinesh D’Souza ’83 got their starts.

As his involvement with Phi Delt deepened, Joe began to especially appreciate the intergenerational quality of the brotherhood. After he graduated, Joe came to Hanover every fall for rush weekend, which doubled as a reunion for the fraternity’s many alumni. He hardly ever missed a brother’s wedding or bachelor party. One time, after his flight had been can-celed due to a storm, Joe drove all night to Chicago from New York to attend the wedding of John Paro ’05. For the wedding of another friend, Andrew Kallmann ’05, he waited years before giving the couple a gift. A few weeks before he died, Joe presented Kallmann with a framed 100-year-old postcard of the hotel where the wedding was held.

Joe found his creative home at the Review. The independent conservative paper served as Joe’s school of journalism. He threw himself into it, working all night long several nights in a row, many times alone, listening to a single song on repeat, writing and rewriting, editing, doing layout, finding art—in short, putting together each issue. By the time I joined the Review as a freshman staff writer—just a few months after Joe had graduated in 2005—he was already a legend within the paper’s ranks. The then-chairman of the Review’s board, James Panero ’98, says that as editor, Joe “displayed literary and critical gifts that were sui generis and fully-formed.”

As editor Joe steered away from arm-chair opinionating and national politics. Instead, he did real reporting about Dartmouth issues. In 2005 he published an expose of the controversial Student Life Initiative (SLI), the project launched by President James Wright in 1999 to end Greek life “as we know it,” as The Dartmouth reported at the time. Joe had acquired hundreds of confidential documents from the trustee committee on SLI from a secret source and published some of the more damning items in the Review’s pages.

What motivated Joe’s editorial vision wasn’t anger or frustration toward those with whom he disagreed, but his love of Dartmouth and its traditions. The Dartmouth of today, he thought, was wonderful—but it was also a pale shadow of what it once was. In a 2005 article called “Threnody for Old School Dartmouth,” Joe complained that “New School Dartmouth” was like “an industrial mill [churning out] résumé after résumé of sufficient pedigree and illustriousness to land a job.” Old School Dartmouth “rejected this kind of abstemious, risk-less living.” It embraced the intensity of ritualized brawls and excessive drinking. It celebrated the horning of professors and the rushing of the Green.

“Easy as it is to dismiss Old School Dartmouth as a culture of misbehavior, vulgarity, and debauchery,” Joe wrote, “that culture, which loudly predominated at Dartmouth for decades, did have a prescription for producing creative, adventurous, spiritual fellows.” Fellows, Joe argued, such as Robert Frost, class of 1896—fellows who went all out.

The paper also brought Joe in contact with emeritus professor Jeffrey Hart ’51, the former Reagan and Nixon speechwriter, National Review editor and English department gadfly who helped launch the Review in the 1980s from his living room. Hart quickly became an important mentor to Joe. Over lunches at Murphy’s, Hart gave Joe an education in political philosophy. But the most important lesson he taught Joe is that there’s much more to life than politics. Hart was conservative, but he wasn’t an ideologue. He was more passionate about literature and tennis than public policy. During the past presidential election, as friendships were being torn apart over politics, Joe liked quoting an article by Hart that appeared in these pages in 1976 called “The Ivory Foxhole”: “Existence, thank God, includes much more than opinions.”

Downplaying his own talent, Joe often said he “caught a break” getting into journalism—a statement that reveals his characteristic modesty.

Hart also played an instrumental role in Joe’s career at the Journal. As Joe was getting ready to graduate, Hart sent Joe’s cover letter and clips to his former student, Gigot, editor of the Journal’s editorial pages. Hart attached his own recommendation to the bundle, which essentially said, “You’ve got to hire this guy.” Gigot read through Joe’s articles and was immediately struck by the quality of his writing and his “nuanced mind.” He hired Joe as an intern immediately after he graduated in 2005 and then full-time that autumn. “It was the best decision I’ve made in my 16 years in this role,” Gigot says.

Joe began as an assistant editor on the editorial features page, where he edited opinion pieces and wrote the occasional article. Some of his early pieces, such as profiles of Tom Wolfe and Buckley, touched on themes Joe wrote about for the Review. The title of the Buckley profile was, simply, “Old School.” Other pieces were more polemical, such as his notorious 2006 takedown of bloggers as fake journalists, “The Blog Mob,” which earned him some serious hate mail from said bloggers. Then, in 2007, Gigot moved him over to the editorial page, where during the next decade Joe would write a total of 1,353 unsigned “Review & Outlook” pieces.

One day Gigot came by Joe’s desk and asked him whether he’d like to cover healthcare. Without skipping a beat, Joe said, “Sure.” In 2011, at the age of 28, he won the Pulitzer Prize in Editorial Writing for, in the words of the Pulitzer committee, “his well-crafted, against-the-grain editorials challenging the healthcare reform advocated by President Obama.”

Soon after Gigot assigned Joe the healthcare beat, the Journal started receiving subscriptions to academic publications such as Health Affairs. Technical books and research papers started piling up on his desk. He got to know sources from every corner of the field—Capitol Hill policy wonks, insurance executives, academics. And he was one of the few people who actually read and understood the behemoth Affordable Care Act.

When Gigot asked Joe to cover the 2016 presidential election, it was the same: Joe read every single book he could find either by, about or related to Donald Trump—including The Bitch Switch by Omarosa, the former Apprentice star who serves in the White House. For his piece, “Donald Trump, Meet Your Customers,” Joe did what he described as the “slow, bleary-eyed scutwork” of reading 26,000 online reviews of Trump products (“remember, kids,” he wrote, “this is what happens if you go into journalism”). When he learned of the existence of a Trump board game, he tracked one down and made the Journal’s interns play it. It’s unclear whether Joe ever slept.

That was the way Joe worked. He was endlessly curious and delighted in learning. When his family and friends cleaned out his small Manhattan apartment they found some 1,300 books stuffed into it floor to ceiling. There were more than 30 books on or about F. Scott Fitzgerald, at least 15 books about the Journal and some 17 by the literary critic Joseph Epstein. Joe’s Dartmouth books included the Letters of Eleazar Wheelock’s Indians, the proceedings of the 1971 Dartmouth “Conference on Computers in the Undergraduate Curricula,” the coming-of-age tale Ten Years to Manhood by Clarke Church ’49 and a pamphlet by Noah Riner ’06 titled “Rollins Chapel Chancel Windows: A History.” There were also books about Chris Farley and David Letterman, including Home Cookin’ With Dave’s Mom by Letterman’s mom, Dorothy. These books were all annotated with Joe’s signature, the location where he acquired them and the date he read them.

Joe also found time to indulge his mischievous side at the Journal. In 2011, around Oscar time, the paper’s editorial board members put together a list of their favorite movies. Joe’s colleagues honored films such as Ben-Hur and Patton. Joe’s submission: the children’s film Kangaroo Jack, which he described as “an allegory about the obsessive pursuit, through the Australian Outback, of an elusive marsupial with a fortune hidden in its pouch. You might call it the thinking man’s Moby Dick.” In the spring of 2016 he found out that lines of Ivanka Trump scarves were being recalled because they were flammable. The scarves were made in China, a fact that Joe found hilarious, and made the basis of an editorial called “A Trade Lesson in Trump Scarves.” He managed to track down one of the scarves and wore it to an editorial meeting, asking Gigot, half seriously, if they could light it on fire on the set of the Journal Editorial Report to see if it would actually burn.

Joe always said he wanted to stay at the Journal as long as the paper would have him. What would have been next for him there? According to Gigot, Joe was about to receive his own weekly column, in which he’d cover national issues alongside columnists such as Peggy Noonan and William McGurn. Eventually, Gigot says, Joe could have “been editor of this page for sure.”

Joe had other goals, too, that he hoped to accomplish alongside his work for the paper. Most especially he wanted to write a book—and, in fact, he did. Around the time he won the Pulitzer, he wrote a detailed policy volume on healthcare. But when he showed it to publishers, they wanted to transform it into a polemic about how Obamacare ruined America—something “dripping with blood,” Joe told a friend. Joe didn’t want that, so he turned down the book deals, even though one of his goals was to publish a book before he turned 30.

Among his many idiosyncrasies was taking notes on 3-by-5-inch index cards. After he died his parents and colleagues found hundreds in his apartment and at his desk at the Journal. On some of them he jotted down goals: “Write about a hundred editorials a year—PG,” a statement attributed to Gigot. On others, memorable advice: “Don’t lose your own voice when you write under your own byline—TV,” a quote from his old boss, Tunku Varadarajan. On others, wisdom from old masters: “Produce again—produce; produce better than ever, and all will be well—Henry James.” But many of those index cards contained brief descriptions of scenes, short character sketches, bits of dialogue—the fragments, it seems, of a novel. On one he wrote: “Character like Nick Carraway, a Charles Ryder who is a guide for the reader”—referring to characters from the novels The Great Gatsby and Brideshead Revisited, respectively.

It’s tragic that Joe never had the chance to write a book. There’s nothing he would have loved more than adding his own small contribution to the historical record—and specifically, to Dartmouth’s. The healthcare book aside, Joe’s real yearning was to write a work of history covering the College’s last 100 years. But even if his words aren’t preserved in binding—not yet, anyway—he did leave a lot behind. Of course, there was his work at the Journal, which reached millions of people and affected the course of national politics. But there was also his character. Joe was everything that many successful people are not—humble, generous and kind. He didn’t suffer fools gladly, but he had grace. From an early age his big-heartedness touched many people who crossed his path, and that may prove to be his most powerful legacy.

Read a selection of Rago’s writing shared by The Wall Street Journal following his death in July.

Emily Esfahani Smith is an editor at the Hoover Institution and the author of The Power of Meaning: Finding Fulfillment in a World Obsessed with Happiness.

Illustration courtesy The Wall Street Journal