Interviews With Young Alumni

Frozen Fieldwork

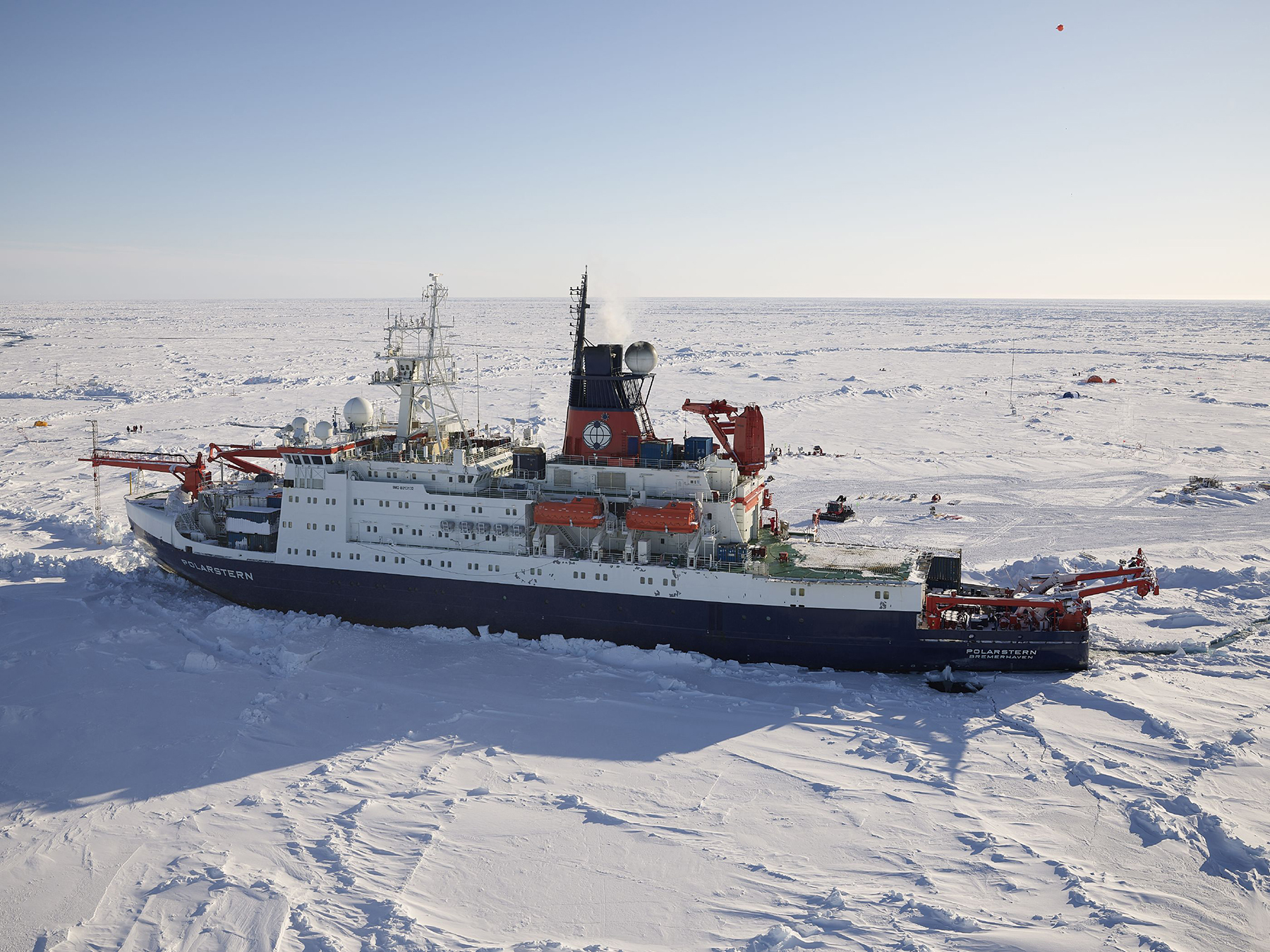

The largest polar expedition in history, MOSAiC (Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate), took place in 2019-20 aboard a German icebreaker called the R/V Polarstern. The goal was for more than 300 scientists from 20 different countries to conduct hundreds of research projects and amass data on conditions in the Arctic, leading to a better understanding of climate change there. David Clemens-Sewall, a Ph.D. student who majored in chemistry and earth sciences as an undergrad and had spent several seasons in Antarctica for his thesis, was one of several Dartmouth-affiliated researchers who participated.

What kind of data were you tasked with collecting on this expedition?

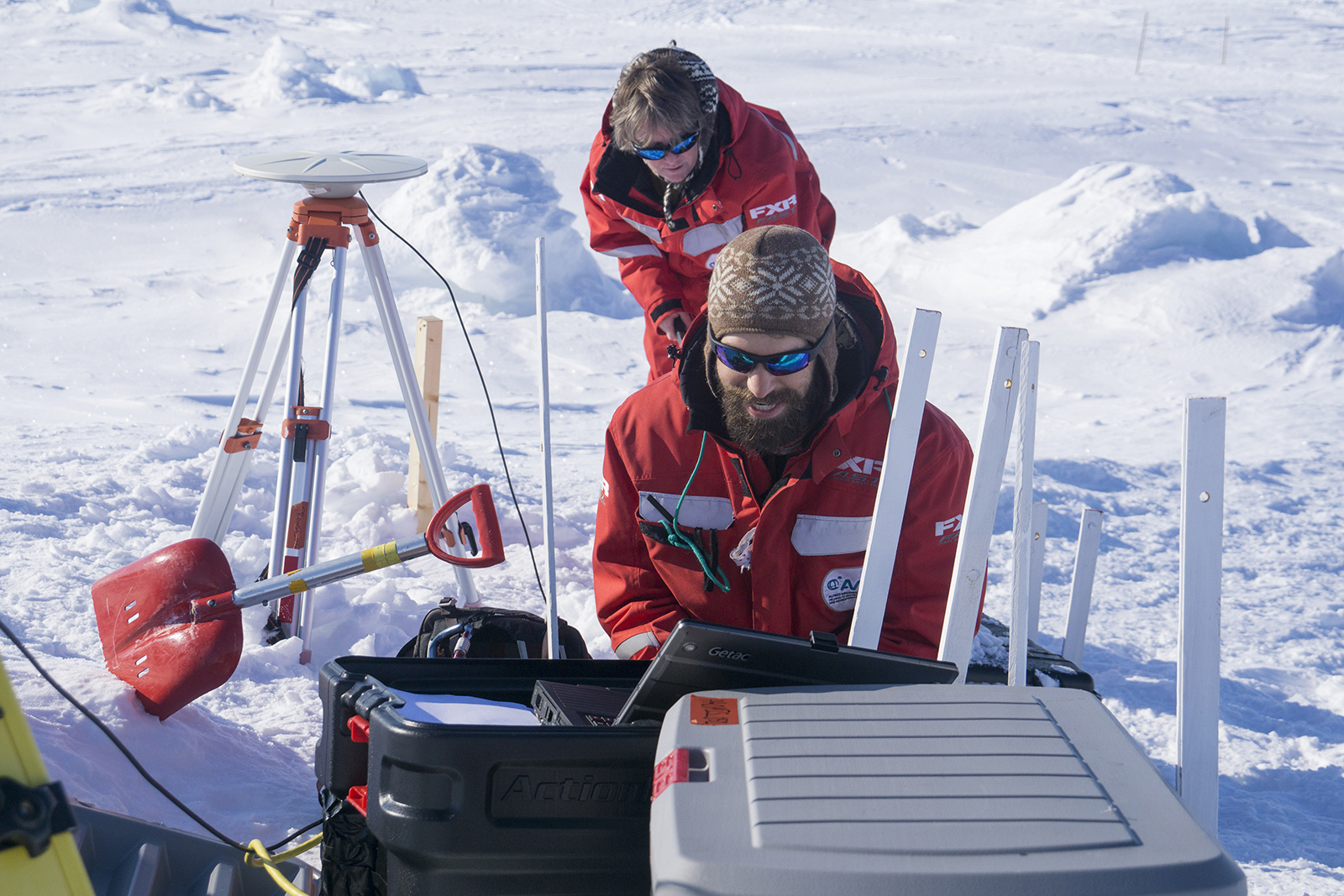

The goal was to understand how snow and ice are changing in the Arctic sea. Most of the measurements I was making were direct measurements of how much ice and snow is there, how is it distributed spatially, and how is it changing through time. The major tool I used was a terrestrial laser scanner, or a LiDAR, which is basically a rotating laser that I used to map the surface of the snow. You can make 3-D maps and then, by repeatedly making these maps through time, you see how the snow surface or the ice surface is changing. This photo (below) is me attempting to repair something in the field. The instrument here is the LiDAR itself. There’s a laser that shoots out of this opening on the left side of the instrument, and then the whole thing spins around.

I should say this wasn’t really a repair, I’m just trying to adjust the settings. In practice, I never successfully repaired it in the field. It was always too cold. I always ended up bringing it back on the ship. This was a day when it had just warmed up. It was probably only around 10 degrees Fahrenheit, but it had warmed up, so I was feeling really good. Turns out it’s still too cold to be messing around with some of these things.

How did you get involved with MOSAiC?

When I came back to Dartmouth I started in a master’s program and then after a couple of years I realized I wanted to stay on for a Ph.D., but the grant only had enough time for a master’s. Right around the time that I was making that decision, the opportunity to be a Ph.D. student on MOSAiC came up. One of the other graduate students mentioned that they were looking for someone to carry out this research and needed someone with a certain sort of track record and set of interests. So I’m still a Ph.D. student at Thayer and my dissertation research is on MOSAiC.

When were you aboard the Polarstern, exactly?

I left the States in mid-January and got back mid-June. But there’s a significant amount of travel time to get there and back. We had to take another icebreaker to get to this location. I got to the Polarstern at the end of February and left in the middle of May.

Did that end up being longer than planned because of Covid?

Sort of. The program was broken up into legs. Originally there were supposed to be six legs, each two months long, with some travel time on either side. Because of Covid, they didn’t get to exchange the winter and spring legs. So everyone who I went out with in the winter, most of whom were planning to come back in April, stayed until June.

Was there time for fun, too?

Occasionally. It’s sort of an all-encompassing thing where you wake up, go out on the ice, work all day, and then process data or fix equipment in the evening and get ready to do it again. But we had lots of time to relax on the transit to and from the boat. And we usually tried to take Sunday mornings off unless there’d been bad weather the previous three days.

What qualifies as bad weather in the Arctic?

The big challenge is visibility. It’s a significant safety problem if you can’t see. Especially when you get low clouds, the sunlight is all diffuse, the wind starts blowing, and the snow really picks up, you can get to the point where you just can’t see where you’re walking. I don’t think we ever had any limitations on temperature. I think we were supposed to not work outside if it got below minus-50 Fahrenheit, but the coldest it got was around minus-42. We did occasionally have issues where, because the ice was fracturing and moving around, occasionally the ice would push the ship in such a way that you couldn’t disembark because the gangplank could no longer reach over.

Could you hear the ice moving when you were onboard the ship?

Oh, yeah. Especially down in the hold, where the gym was. If you were in the gym, you’d hear it sort of crunching back and forth.

Did you see any polar bears?

Just one. They like to hang out where the ice is more broken up. Where we were, it was moving a lot, but it was still 95-percent ice.

Of all the data that you collected with MOSAiC, how much of it is immediately useful?

As far as scientific utility and increasing our capacity for understanding the system, a lot of it. I plan to have something published this winter. One of the real strengths of MOSAiC is that I was surrounded by other scientists also collecting data on different processes that interact. In the coming year or two a lot of the data will be used in collaborations that haven’t been possible before.

What is one thing that you wish people from other fields understood better about your field?

Realizing how much we have to offer each other, in terms of things we know and the tools that we have. For example, although I study snow and sea ice, a lot of the tools I’m actually using to do this were developed in the medical imaging community. I have no doubt that there are innovative ways of not only analyzing data, but also communicating results, spreading information, doing outreach, all that stuff, that people in other fields have put a lot of work into, that would be really valuable for us to take advantage of.

How did you get to where you are now as a Ph.D. student at Thayer?

After undergrad I wanted some experience that wasn’t in academia. I worked for a proprietary trading firm in Washington, D.C., called DC Energy, where basically we were building computer models of the electricity grid and trying to predict what future power prices would be and then the firm made money off of those predictions. It was cool to see how some of the techniques and things I had learned could be applied not just to geophysics research, but also to other systems. After about a year or year and a half of that, Dartmouth professor Bob Hawley reached out to me because he had another grant and needed someone to do geophysics research in Antarctica again. I was ready to move on to something else and this seemed like a good way to keep learning and also move back into more traditional geophysics glaciology research.

How did you end up deciding to study that topic when you were an undergrad?

Probably the most important factor was I went on “The Stretch,” the earth sciences foreign study program, and Bob was the faculty advisor for the glaciology component. I got to know him a little bit then and at the same time I was realizing that I really liked the science of chemistry, but being in a lab every day was just not where I wanted to be. And so I was looking to move to something else. The combination of the kinds of geophysics that we study in glaciology are really interesting from a scientific perspective. And of course there’s also a climate change component—if we can understand these processes better, maybe we can help people adapt to climate change. So that’s how I got into it.