In the early 1960s a psychology professor asked the 25 students (all males) in his class to raise their hands if they felt they were never going to get married.

No hands went up.

“He snickered and said the Kinsey report said it was definite that two or three of us might never get married because we were gay,” recalls one of the students, Ed Hermance. The prof, he adds, was “almost taunting those of us who were in the closet.”

Indeed, Hermance kept his sexual orientation a secret. It’s no news flash that the College didn’t exactly extend a warm welcome to gays during the late 1950s and early 1960s. “Dartmouth has always had a complicated relationship with men who are not perceived as virile, masculine, athletic or outdoors-oriented enough,” wrote Allen Drexel ’91 in his senior thesis on the history of women and gay men at the College. “People who were not perceived as up to snuff in the manliness department were stigmatized and dramatically differentiated from the other guys, who used this alienating gesture to reinforce their own sense of self as real men.”

But 13 years after his graduation Hermance did out himself—to the entire alumni body—with a note to his class secretary, Arthur W. Hoover ’62, who ran it in the Alumni Magazine’s Class Notes in the June 1975 issue.

“Dear classmates,” he started. “During this lull in the flow of wedding, birth and promotion announcements, perhaps this is a good time for me to announce my non-marriage and rambling occupational motion, both of which stem from the fact that I’m gay. What follows is offered in the hope that reflecting on our common past and on my subsequent experience will be useful in changing the present, both at the College and in the many places we all are now.”

Hoover turned his entire column over to Hermance’s letter, which concluded with several calls to action, including “talk about gayness, homosexuality, etc. It doesn’t matter much what you say and think now, the talking itself is what’s needed. The silence is deadly.”

The silence didn’t last long. During the ensuing late 1970s Hermance started hearing from alums interested in forming a group that would support gay alumni and student interests. From his hometown of Philadelphia Hermance published a newsletter for a small following that began calling itself Dartmouth Lambda.

Around the same time gay students on campus started organizing in the face of glaring, and sometimes violent, discrimination. As Drexel described in his thesis (titled “Degrees of Broken Silence: Dartmouth Man, Gay Men and Women, 1935-1991”) the inclusion of women on campus and the “slow erosion of Dartmouth’s he-man mythology appeared to create an opening, however tiny, for the discussion [of homosexuality].”

When students such as Stuart Lewan ’79 and Bill Monsour ’77 formed support groups for gay students, they and others became targets of discrimination and ridicule. In one example from the early 1980s reporters from The Dartmouth Review reported on a confidential meeting of the Gay Students Association (GSA) and published the members’ private, personal stories.

So in 1983 Hermance sat down and wrote another letter responding to what he today calls a “crisis at the College.” Published in the May 1983 Alumni Magazine letters to the editor section, his letter called for student support and criticized the administration’s decision that year to eliminate sexual orientation from the list of grounds on which the College cannot discriminate. Hermance cited a letter from President David McLaughlin ’54, Tu’55, to the College’s affirmative action review board in which McLaughlin claimed “the affirmative action plan is the wrong place to make this statement [of non-discrimination based on sexual orientation]” because, he argued, it would only apply to employees and not students.

Hermance called on other interested alumni to contact him and organize against these policies and to support the GSA. “The response was just terrific,” he recalls. The following year McLaughlin reversed his position and the board of trustees voted to extend equal opportunity protection to gay and lesbian students in November 1984.

The small network Hermance had cobbled together from Philadelphia eventually moved its center to New York City, home to more alumni, and became the Dartmouth Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual & Transgender Alumni Association (DGALA) in 1984. Chuck Edwards, Adv’86, took over the reins soon after graduating, mainly, he says, “because I had computer skills.”

In April 1991 Edwards (now a tech consultant in New York City) was involved in DGALA’s struggle to gain recognition by the College as an affiliated alumni group. The Freedman administration initially refused. The New York Times reported on the wrangle, outraging students and alumni. They responded with public protests and a letter-writing campaign that led to official College recognition in June 1991, bringing with it the help and resources that the Office of Alumni Relations provides to affiliated groups. The administration had finally caught up with the times.

Current DGALA president Susi Kandel ’00 acknowledges Hermance was the catalyst for what today is an organization with 750 members in 40 states and 11 countries. “Ed’s letters forced the Dartmouth community to acknowledge the presence of gay students…and reflect upon the challenges faced by those students in a place, and at a time, when such things were seldom discussed,” says Kandel. “His letters provided comfort to countless gay students and alumni who were finally able to understand that they were not alone.”

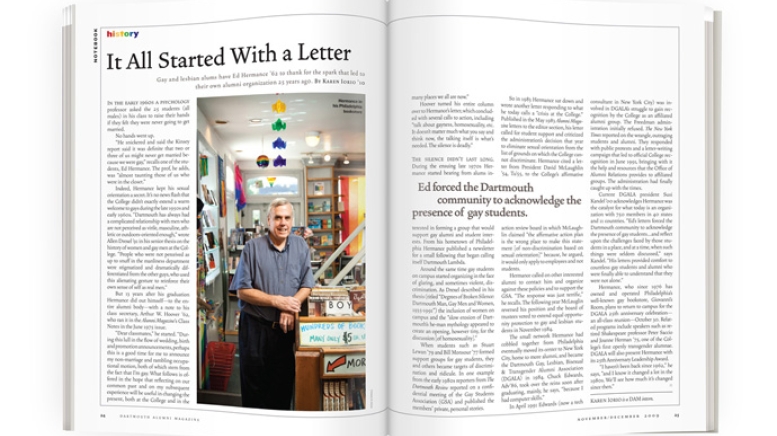

Hermance, who since 1976 has owned and operated Philadelphia’s well-known gay bookstore, Giovanni’s Room, plans to return to campus for the DGALA 25th anniversary celebration—an all-class reunion—October 30. Related programs include speakers such as retired Shakespeare professor Peter Saccio and Joanne Herman ’75, one of the College’s first openly transgender alumnae.

DGALA will also present Hermance with its 25th Anniversary Leadership Award.

“I haven’t been back since 1962,” he says, “and I know it changed a lot in the 1980s. We’ll see how much it’s changed since then.”

Karen Iorio is a DAM intern.