Captain Comeback

The first bumper sticker I saw during my freshman year read simply, “Dartmouth Will Win.”

When it came to football that was no boast, just fact. In the previous decade Dartmouth won eight Ivy League titles. The team won the Lambert Trophy—the best in the East—twice with coach Bob Blackman’s undefeated 1965 and 1970 teams. In the three years before I arrived at Dartmouth, the team suffered only two losses.

Winning was an expectation, and football weekends reflected it. Cars streamed into Hanover every other Saturday. Bonfires, tailgates, and pregame cocktail parties covered the campus. Spectators filled the stands on both sides of the field as each class tried to outdo one another in showing its school pride.

Newly minted on the freshman football team in 1973, I had been well indoctrinated into this winning culture. I had two older brothers on the team—Jim ’74 and John ’76—and I knew many of the players before I ever arrived. Despite some alumni grousing that this year’s team was too small and too slow, all the players carried the belief that Dartmouth would win. I couldn’t wait for the season to start.

Then the unthinkable happened. A 108-yard kickoff return cost Dartmouth its opener against the University of New Hampshire, 10-9. The 0-1 record went up on the locker room blackboard like a medieval curse. Although shocked by the upset, the players remained upbeat. No one panicked. Expectations stayed high. Everyone buckled down. Redemption would come the next Saturday.

Only it didn’t. The varsity lost to Holy Cross. For the first time in 110 games Dartmouth didn’t even score a point. The players were stunned into speechlessness. As both losses were non-league games, however, a win against Penn the next week would get the season back on track.

Despite an early 16-point lead, Dartmouth lost its league opener, 22-16. The reigning Ivy League champions were 0-3.

“The world, at least from our perspective, was upside down,” my brother, Jim, says of the loss.

Captain Herb Hopkins was so furious he threw his helmet against the blackboard and swore they would never lose another game.

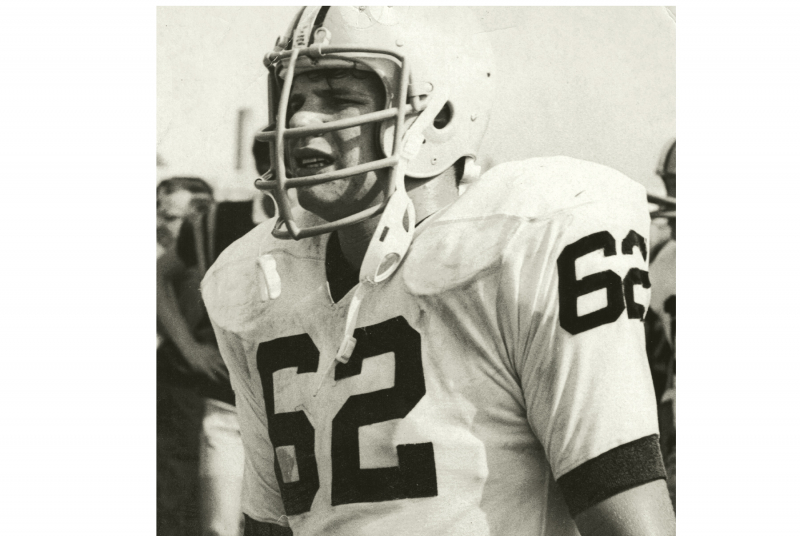

One of those rare people who lit up every room he entered, Hopkins had a force of personality to match his formidable guard’s frame. An English major who was comfortable debating the sharpest of intellects, he lived large, laughed loudly, and took great joy in those around him. His smile was as infectious as it was mischievous, and his enthusiasm could motivate you to move mountains.

An English major who was comfortable debating the sharpest of intellects, he lived large, laughed loudly, and took great joy in those around him.

“Herb had a combination of incredible toughness and strength,” says teammate Tom “Turk” Csatari ’74, a third team All-American defensive end. “Couple that with a football intellect, and it made playing against him scary and potentially harmful. I saw what he did to other players, and it wasn’t pretty.”

The night after the Penn loss, however, Hopkins left campus unexpectedly. His father had suffered a heart attack, and he went home to bury his dad. He was gone all week. For the players it was a sobering time. Most had never confronted, let alone thought about, the death of a parent. Everyone was worried—about Hopkins and the team.

During practice that week players looked as though their confidence had been shaken. The swagger was gone. On Friday the team was already loaded onto the bus to Providence, Rhode Island, when Hopkins strode across the Green. Silence took over the bus as he climbed aboard. He stared down each player, his message clear: I didn’t come back here to lose.

The team beat Brown, 28-16. From that point on, Hopkins’ resolute fury took over the team. He challenged seniors to lead, and they rose to his challenge. Practices were sharper, the execution of plays crisper. Everyone dug deeper.

There was no resisting him. I was in the training room getting taped up one Monday when Hopkins walked in. It was a rainy day, and he wore a huge hat right out of a Humphrey Bogart movie, water spilling from its brim.

“Irv, are we going inside?” he asked the trainer.

“No, Herb, Coach says we’re outside.”

“That sonovabitch! Half the team is already hurt. There’s no way we’re going outside.”

Head coach Jake Crouthamel ’60 walked in right behind him.

The whole room froze. Hopkins turned around and didn’t miss a beat. “What the hell are you thinking?” He poked Crouthamel’s chest. “There’s a monsoon outside.”

“We’re going outside, Herb.”

“Well I’m not. And none of the seniors will either.”

Thankfully, Crouthamel took Hopkins up to his office (so the rest of us could breath again). But that afternoon we practiced inside Leverone Field House.

Beating Brown was one thing, Harvard another. In a packed Harvard stadium, three crucial goal-line stands by Dartmouth’s defense led to a 24-18 win. Momentum restored, Dartmouth won every other game—against Yale, Columbia, Cornell, and Princeton—most by a sizable margin.

After the Princeton victory, with the title in hand, the team celebrated in New York City. As players descended from the bus in front of their hotel, a theater marquee across the street featured the play That Championship Season.

“Herb was instrumental in Dartmouth winning the title our senior season,” says Csatari. “His teammates and I will never forget the turning point in the season after our loss to Penn. Captain Herb came back and helped us to defeat Brown and start one of the greatest comebacks in Dartmouth football history.”

Hopkins went to Alaska after graduation and spent some time as an amateur boxer. He returned a few years later to attend the Wharton School of Business, and then he had a successful career as an investment banker. He met his wife, Toni, after making a rare decision not to indulge in a beer chugging contest so that he could talk to the beautiful woman in the corner of the room. They had three great children.

But Hopkins faced other challenges. His fierce competitiveness helped him wage a 20-year battle against Parkinson’s disease. For many years he led a successful fundraising effort called “The Green Machine” on behalf of the Philadelphia Parkinson’s Council. He pushed himself ruthlessly, often riding his bicycle through the city until his body gave out and did pushups late into life, long past when his mind had sought greener pastures.

This past June his struggles against the disease came to an end.

“I first met Herb on a fall afternoon on Chase Field during freshmen football practice,” my brother, Jim, eulogized. “There were almost 150 of us trying to make the team. It was a hot day, the line for each drill was long, and we had only limited chances to impress the coaches. As I stood near the middle of one of those long lines, someone shoved me in the back of my shoulder pads. I spun around, irritated that my focus had been broken. It was Herb. His face was covered with sweat and dirt. He squinted through the facemask of his helmet and pointed to the hillside above the field that was resplendent with the turning fall leaves. He smiled and in a South Philly twang said, ‘Have you ever seen anything more beautiful in your life?’ ”

Joe Gleason lives in Virginia with his wife, Mary Margaret.