Sarahi Pineda ’18 recalls one of her biggest challenges as an undergraduate advisor (UGA): a resident of her dorm who could often be heard fighting with her boyfriend. One day Pineda saw him trying to lock the resident out of her room. “In the moment I debated intervening, but I knew somebody was in trouble, and we were taught in our training to not be a bystander and let something like that continue. I was going to address it because I wanted them to know that there was someone in the dorm who would feel responsible for coming up and asking what was going on.” The troublemaker ultimately let both his girlfriend and Pineda into the room, where Pineda was able to assess that the situation was safe. She also later talked to the resident to offer support.

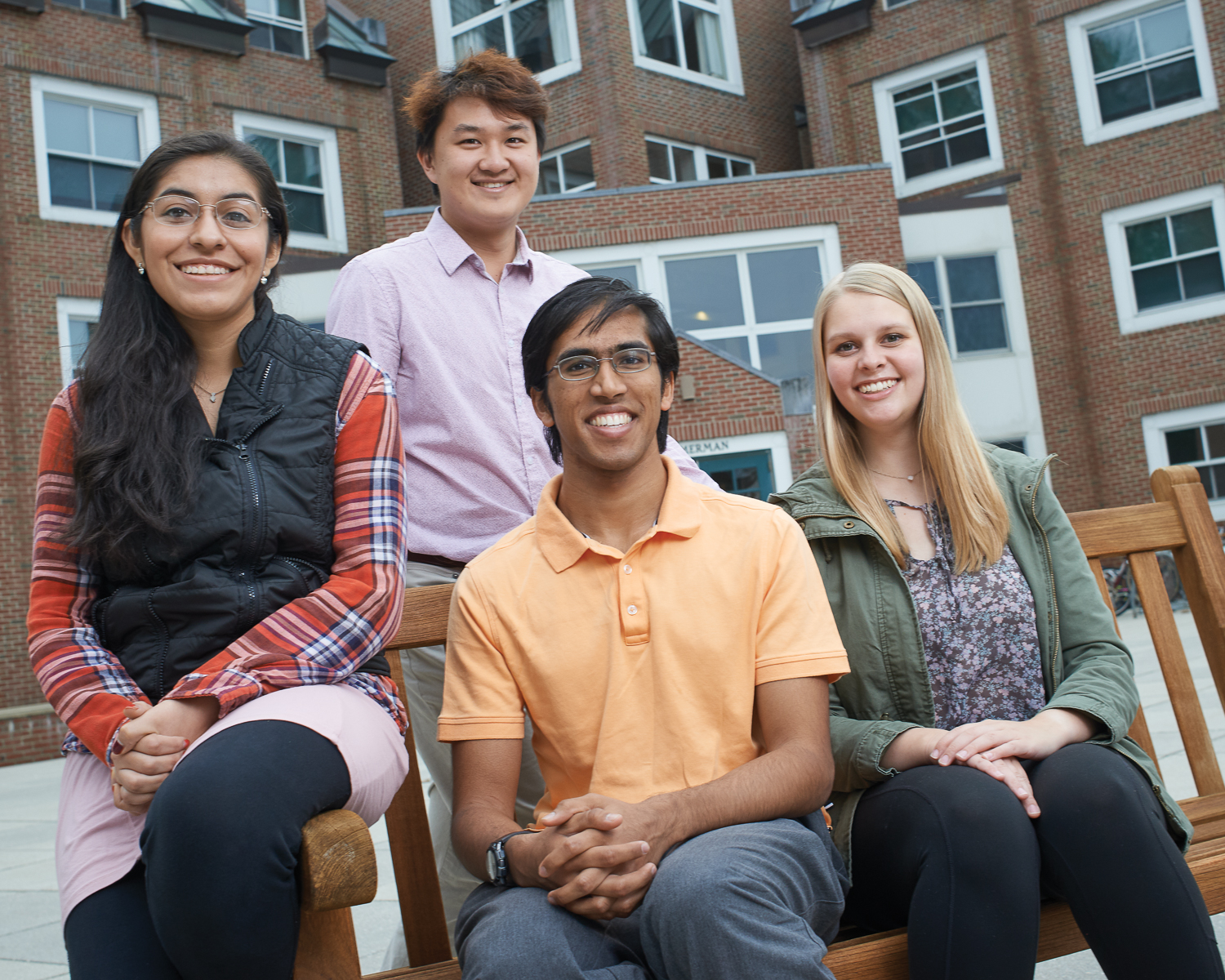

Though on-campus residents at Dartmouth benefit from several full-time staff members, including community directors, house professors, graduate-level resident fellows and assistant directors of residential education, the people most likely to understand students are their fellow undergrads. “The challenge and cool thing about being a UGA is that you’re given training, but you still have to use your own judgment and experience to help a student,” says Andrew Sun ’18, a physics major from Charlotte, North Carolina, who is in his seventh term as a UGA.

Even with added infrastructure and support systems brought about by the new house communities, the personal support long provided by UGAs remains critical, especially for first-year students.

The need for that one-on-one connection is highlighted by a recent survey of nearly 20,000 students at 40 post-secondary institutions conducted by the American College Health Association. In it, 24 percent of students reported that anxiety had affected their academic performance. Thirty percent were affected by stress, 15 percent by depression and 10 percent by concern for a troubled friend or family member.

Anirudh Udutha ’18, a UGA from Atlanta, says residents of his dorm have approached him to talk about everything from relationships to mental and emotional health. “Sometimes they’re worried about someone else who is feeling depressed. They might be worried about self-harm. They might be going through something back home. It can take up a lot of their mental space and they might not be able to deal with their class loads,” he says.

UGAs report to assistant directors of residential life and are responsible for “facilitating the development of communities that support and enhance the intellectual, cultural and social development of residents,” according to the office of residential life. They have the leeway to be creative in how they create a sense of community, says Katharina Daub, associate director of academic initiatives, first-year programs and living-learning communities. “Some plan many group events and others prefer to connect with residents one-on-one,” she says.

“We pick up on things other people wouldn’t if they didn’t live in the same space.’’

Always upperclassmen, the roughly 100 UGAs chosen from as many as 400 applicants—and trained by the office of residential life—are assigned to both freshman and upperclassman housing. The College hires one UGA for every 20 to 40 residents, depending on the term and housing situation. As paid staff members—each receives a stipend of about $2,000 plus a $1,500 credit toward student bills per term—UGAs are expected to dedicate 15 to 20 hours per week to conduct walk-throughs of their dorms, report drinking and other violations, build relationships with residents, and organize floor meetings and social events.

UGAs might also supply treats and encouragement during finals or issue invitations to meet one-on-one for coffee, so they are likely to be the first to notice when a student has problems. “We pick up on things other people wouldn’t if they didn’t live in the same space,” says Pineda. “Sometimes you stop seeing residents as often, or you stop seeing them at a certain time. If they don’t come out of their rooms, stop responding to your emails and don’t come to your events, something might be wrong.”

“This is not a campus that’s free of bias or sexual assault, so UGAs support students when something does happen,” says Daub. “UGAs can make sure students are connected to the appropriate resources and make sure reports are made confidentially.”

UGAs must be mature and open-minded, says Daub. “Things we focus on in the selection process are understanding of community and how to build a healthy community, [the ability to] hold peers accountable, as well as knowledge of diversity, identity, social justice and where are they trainable,” she explains. UGAs attend off-campus training where they sleep in cabins, participate in outdoor activities, learn campus policies and protocols, and become familiar with the array of College support systems available.

“The training with campus colleagues was the most useful,” says Maya Frost-Belansky ’20, who is from Boulder, Colorado. “The office of pluralism and leadership came in and did a session about being sensitive to diversity. A representative from WISE of the Upper Valley, a sexual assault advocacy organization, came in and spoke to us about the resources they offer. We learned how to be a bridge between them and residents.” UGAs also learn evidence-based techniques for communicating with residents, such as motivational interviewing, which is designed to elicit self-reflection and opportunities for growth.

Daub notes that UGAs need a lot of support also. They can find that from fellow UGAs, their supervisors or counselors, if necessary. “If a UGA is helping a student with a marginalized identity, for example, and the UGA is of a marginalized identity, at some point there may not be enough emotional energy to go around,” Daub says. “The training committee introduced me to a wellness coach who opened my eyes to the fact that I’m so busy I need to remember to budget time for myself,” says Frost-Belansky.

UGAs can derive satisfaction from knowing their efforts are appreciated: Recent year-end surveys of first-year students show that they consider UGAs along with trip leaders as the people who most helped them transition to Dartmouth. “If I can make a difference for even a few residents, that’s the ultimate goal,” says Frost-Belansky.

Tiffanie Wen is a freelance writer based in Lebanon, New Hampshire.