One hundred fifty years ago Dartmouth alumni and students were not immune to the patriotic—and rebellious—fervor of the times.

The College’s plaque honoring “the sons of Dartmouth” who died in the war, housed in the Rauner Library lobby, lists 73 alumni, 63 of whom died fighting for the Union and 10 for the Confederacy. The class of 1863 alone sent 56 men into battle—53 for the Union and three for the Confederacy.

In 1944 College President Ernest Martin Hopkins, class of 1901, declared in a speech that during the Civil War “no college had a larger portion of her men enrolled in the armed forces,” according to historian Charles Wood. Here are just a few of their stories.

The Ride of a Lifetime

The Ride of a Lifetime

The ultimate off-term for students in 1863?

For the Dartmouth Cavaliers it meant saddling up and heading off to the War Between the States, full of visions of their own heroism and patriotism.

They had no clue what they were in for.

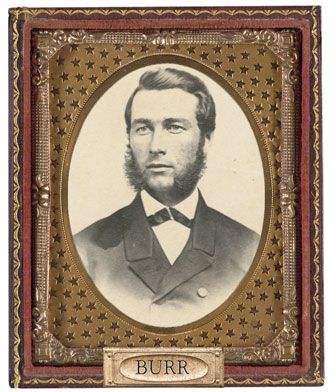

When Abraham Lincoln called for Union troops to defend Washington, D.C., after the spring 1862 defeat by Stonewall Jackson at Shenandoah Valley in Virginia, Sanford S. Burr, class of 1863, took to his horse. That summer he canvassed campus and crossed the bridge into Norwich, Vermont, to rally support. His proactivity spurred the creation of the College Cavaliers, a company of college men—the majority of whom were Dartmouth students—who embarked on the ultimate summer off-term: a three-month stint in the Civil War. Despite College President Nathan Lord’s concern that a three-month leave would constitute a “serious detriment” to the students’ studies, the College Cavaliers left Hanover on June 18, 1862, just before they would have taken final exams. Though the Cavaliers did not achieve any particularly remarkable feats in battle, they certainly were challenged by the inherently tough conditions of wartime life.

Burr, a “wideawake, courteous [gentleman] persuasive in his talk, and commanding in his way of urging support,” according to classmate S.B. Pettengill, had applied to the governors of New Hampshire, Maine, Vermont and Massachusetts in search of a volunteer army the boys could join. Each state turned him down, but he eventually found backing from the governor of Rhode Island, who offered to accept the company of students to serve three months in the squadron of cavalry Rhode Island was raising. In addition to 35 students from Dartmouth, Burr had rallied 23 from Norwich University, four from Bowdoin College, a few boys from Union, Williams and Amherst, and another 17 young men from Woodstock, Vermont. Their casual mid-June departure from campus as recounted by Pettengill, a company member, seemed to demonstrate a lack of understanding of what they were about to face.

“They had stepped gaily forth from the College Campus without having visited their homes to say, ‘Good-bye.’ There had been no parting scenes, nothing in their course thus far to distinguish it much from the usual vacation experience,” wrote Pettengill.

But this was the Civil War, and the nonchalance of the company was quickly challenged. Upon arriving in Providence and joining up with a local company to form the 7th Squadron of the Rhode Island Cavalry, the sheltered college boys were confronted with the task of working with “just such men as would naturally be enlisted in a city, where, like a net cast into the sea, the recruiting officer gathers of every set.” The Dartmouth men and the unfiltered set did not take to one another. In camp and on the battlefield they “maintained an unwonted degree of exclusiveness in their relations with each other,” Pettengill wrote, due in part to the students’ belief that they were “apt to be equal, if not superior, in endurance under such service to the more horny-handed sons of toil.”

Despite their differences with the rough men who composed Troop A of the squadron, the Dartmouth students of Troop B worked hard at Dexter Training Ground, drilling for up to six hours per day. Unlike at Dartmouth or at home, there were no days off.

“Sunday in camp is not Sunday at home,” company member Isaac Walker, class of 1863, wrote in his journal. “Commands of the officers must be obeyed and the commands of such officers as are in our army are generally given without regard to the day or the hour.” Yet there was still time for socializing, and the college boys found more acceptable companions with whom to spend their free time: Brown students, who invited the Cavaliers to their fraternity halls for “social and literary entertainments.”

At the end of June the company moved to Camp Sprague just outside of Washington. Despite the hardships of Providence, Sprague made Camp Dexter seem luxurious in comparison. To the chagrin of the students, the company continued to train. “They were anxious to give proof of their patriotism at the sabre’s point and earn a little glory,” wrote Pettengill. Disillusionment set in. Not all of the men, it seemed, had understood that war service involved a lot of training and hanging around camp. They were especially peeved by the fact that, as cavalrymen, they were expected to care for their horses.

“They did not understand that they were to be stable boys when they enlisted, and to feed, water, and groom horses did not accord with their ideas of the ‘pomp and circumstance of glorious war,’ ” wrote Pettengill.

Furthermore, they found the city to be “dirty and disagreeable.” Farm animals roamed the streets and their camp, and the oppressive July heat eliminated any desire to sightsee. Pettengill wrote that although the students never entered congressional halls, they still considered the larger questions of the war, debating slavery and freedom from within the confines of their camp.

The Cavaliers’ first exciting moment came after they had moved to Winchester, Virginia, at the end of July. Famous Confederate spy Belle Boyd, known as “La Belle Rebelle,” spent a night at the Cavaliers’ camp as troops escorted her to Washington following her arrest. That evening the boys heard commotion at the picket lines. They later learned that it was a ruse to distract them as Confederates attempted to raid the camp and rescue Belle. The ploy didn’t work.

The rest of the students’ time at Winchester moved in a slow, redundant rhythm. They alternated between picketing, patrolling the roads, foraging for supplies, participating in reconnaissance missions and riding on Confederate raids. They even elicited the pity of some Southern mothers, who, upon learning the young men were college students, made sure they ate well. Their mounts were less fortunate: Many died from inadequate feeding.

It turned out that the Cavaliers might have been right to scoff at their stable duties, because their Dartmouth education paid off when they finally saw combat. While stationed at Maryland Heights, the group was sent to escort two New York infantry regiments arriving from nearby Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, through the woods to the summit of the heights. The 120th New York Regiment, Pettengill noted, “behaved very badly” when it came under Confederate fire. The Cavaliers’ first reaction was to stand before the enemy, where, instead of firing their guns, they “brought into exercise every art of public speaking they had acquired at school in unavailing efforts to arrest the stampede.” Some of them pushed forward into the Confederates, “attempting to do by example what they had failed to do by words.” Despite the Cavaliers’ eventual physical engagement of the enemy, the Confederates took possession of the heights and forced the Cavaliers to flee to Pennsylvania.

“The Rebels are shelling us from the Heights about us and we are giving them as much as they gave us,” Walker wrote in his journal on September 14, 1862. “We are in hope that reinforcements are on their way to us. May God grant us such a gift.”

The Cavaliers did manage one successful military maneuver during their tenure. On their journey to Greenville, Pennsylvania, the 7th Rhode Island captured a Confederate wagon train. Once at Greenville, the students agreed to remain enlisted until the enemy was driven out of Maryland, despite the fact that their term of service had already expired. This allowed them to see action at Antietam,

the bloodiest one-day battle of the war. They formed the right flank of Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s army, helping to force Gen. Robert E. Lee’s retreat across the Potomac back to Virginia and providing President Lincoln with the confidence to announce the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

On September 26, 1862, the students arrived back in Providence. Fall term at Dartmouth had already begun, and the students were eager to resume their studies. Upon their arrival back in Hanover, the students learned they were expected to take the exams they had missed the previous spring when they left school to enlist. Outraged, Burr immediately went back to Brown and obtained a promise from university President Barnas Sears that if Dartmouth expelled the students for refusing to take exams, Brown would accept them. Not wanting Brown to snatch its heroes, Dartmouth waived the tests and allowed the students to begin fall term.

Despite the tedious hours spent picketing and grooming horses and the “lowbrow” Providence men with whom the college boys were assigned to fight, the Dartmouth College Cavaliers saw action on the battlefield, lost only one man—and wiggled out of some final exams. “It was an intelligent, sincere and a worthy service in which these students engaged,” wrote Pettengill, “though like every human work it was transitory and small in itself.”

Escape Artist

Escape Artist

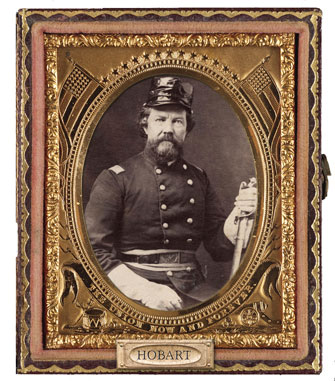

Harrison Hobart, class of 1842, dug his way out of the Confederacy’s infamous Libby Prison and lived to tell the tale.

Harrison Hobart entered the Civil War as a lawyer, Democrat and eager patriot. He was more willing to “fill a soldier’s grave than to stay at home a coward,” remembered Elias Calkins, a fellow Wisconsin colonel and commander who wrote an 1881 book about Hobart. Luckily, Hobart didn’t do either. Acting above and beyond his duties, Hobart took some huge risks, including one that led to his capture. His eventual escape—in one of the more daring episodes of the war—led to the rescue of hundreds of Union soldiers.

Before joining the Union army Hobart had completed a distinguished career at Dartmouth. He founded the Tri Kappa “college society,” now known as Kappa Kappa Kappa, in “the spirit of resistance to class oligarchy and a system of social exclusiveness,” wrote Calkins.

Hobart’s on-campus leadership translated seamlessly into the challenges of wartime. After being elected captain of the company he founded in the 4th Wisconsin Infantry, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the 21st Wisconsin. The battle at Chickamauga, Tennessee, on September 20, 1863, demonstrated Hobart’s fearless determination. During the last day of the battle Hobart’s company kept fighting until the other regiments retreated, even though he had been ordered to fall back much earlier. This mistake, combined with his men’s resolve to “contest all ground” until they were surrounded, led to Hobart’s capture—and that of 70 other men—by Confederate Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne.

The Confederates took Hobart, his men and 1,700 other prisoners to Atlanta by wagon car, then put them in boxcars for a miserable eight-day ride to Richmond, Virginia. There Hobart was jailed with 250 officers in the harsh confines of Libby Prison, where the Confederacy detained a total of 1,200 Union army and navy officers. Hobart’s 1891 account detailed the prison’s conditions. There were no beds or chairs, so everyone slept on the floor at the mercy of the vermin that infested the prison. The lack of glass in the windows and heat in the rooms made the cold months unbearable. Each officer was allowed to write home only three lines per week. Most drastically, to deter a Union rescue mission the rebel commanders had mined the prison and had standing orders for its detonation should the Union make an attempt.

Under these bleak circumstances, Hobart and the prisoners persevered. They played chess and cards, engaged in debates and performed plays. Their greatest accomplishment, however, occurred underground. Four months after their capture Hobart and 24 prisoners completed the construction of a 70-foot-long, 8-foot-deep tunnel that ran from the prison basement to a shed across the street. The prisoners worked on the tunnel each night in teams of two, using a table knife, spittoon and chisel. Before daylight the excavators would close the mouth of the tunnel and replace the bricks on the chimney to conceal its entrance before sneaking back to their rooms. Around 7 p.m. on February 9, 1864, the prisoners began their escape from Libby Prison through the tunnel. The 25 excavators had first priority, but 109 men eventually crawled to their freedom. They dressed in citizens’ clothing to disguise themselves, and a “dancing party with music” on the prison grounds successfully distracted the Confederates as the Union soldiers slipped by undetected.

“It was a living drama,” Hobart wrote. “Dancing in one part of the room, dark shadows disappearing through the chimney in another part.” While the Confederate sentinel stood at his post, “a Yankee soldier was passing his front, and a line of Yankee soldiers were crawling under his feet.” Fifty-seven men evaded Confederate forces and made it safely to Union lines, but the rest were captured along the way. Hobart and three other prisoners made it roughly 80 miles to Union outposts near Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia, aided by a military map of Virginia and a generous slave who guided them around a nearby Confederate cavalry.

Though he had reached safety, Hobart did not give up on the rest of the prisoners. With the approval of Gen. Sullivan A. Meredith, the head of prisoner exchange, Hobart formulated a plan to take back Union hostages. A boat of about 300 Confederate prisoners was sent up the James River to the Richmond outposts for an exchange of equal numbers of Union officers.

This trade was not the end of Hobart’s escapades. After a furlough spent at home in Wisconsin—where he was received as a hero—he rejoined his regiment and was promoted to command the 1st Brigade of the 1st Division of the 14th Army Corps. After Hobart’s service during Gen. William T. Sherman’s March to the Sea, Sherman recommended him for promotion by President Lincoln for meritorious services.

Hobart was finally relieved of command on June 8, 1865. He returned home to Wisconsin, where he moved to Milwaukee intent on pursuing business. He ran unsuccessfully for governor but in 1867 was elected member of the 2nd Assembly District of Milwaukee, where he passed a bill creating Milwaukee High School, advancing his free education mission. He later continued his life of service as a trustee of the University of Wisconsin and practiced law until his death in

1902.

“Gallant Service”

“Gallant Service”

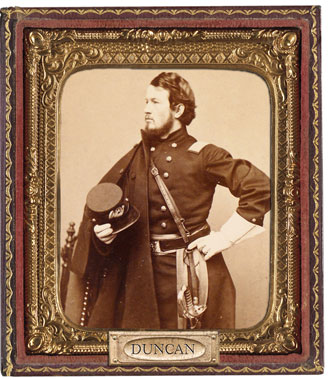

Union army enlistee Samuel Duncan, class of 1858, led the U.S. Colored Troops in the battle of New Market Heights.

One of the great consequences of President Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation—the decree that freed all slaves in Confederate territory under rebellion—was that it finally allowed official black enlistment in the Union army. Many escaped slaves who had crossed Union lines, known as contraband, had already been working for the Union and enlisted in the army as soon as official black recruitment began in 1863. The transition from laborers to soldiers wasn’t easy. Black soldiers were placed in separate brigades led by white officers. By the end of the war approximately 180,000 men, including white officers, served in the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT). Lt. Col. Samuel Augustus Duncan was one of those officers.

Before commanding the 4th Brigade of the 3rd Division of the XVIII Corps, the Meriden, New Hampshire, native had pursued a career in education after graduation. He served two years as the principal of a Quincy, Massachusetts, high school and then returned to Dartmouth as a language and mathematics tutor while acting as commissioner of Grafton County schools. In September 1862 he enlisted in the Union army.

Duncan initially served as a major of the 14th Regiment of N.H. Volunteers. Relegated to Washington, D.C., they were removed from the primary fighting arenas. Duncan began to feel restless. Aware the USCT was searching for officers, Duncan applied, hoping to advance his military career and finally fight. He was promoted to colonel of the 4th USCT Brigade in September 1863. This new position put Duncan’s existing support of black troops into practice. “[It is] much to a man’s credit and honor to lead a black regt,” he wrote to correspondent Julia Jones of East Washington, New Hampshire, in a letter included in Rauner Library’s collection of his 1850-66 correspondence.

After about two months with the 4th Brigade, Duncan was already being commended for his work. “Your regt. has already a good name and none of your friends will be surprised either at that or your ability to manage it better than any other man,” Adj. Alexander Gardiner wrote Duncan in November. “You no doubt will have a great influence on your colored friends. They naturally have a great regard for you and your example and words and advice will be constantly producing results,” the Rev. E.T. Rowe predicted in a letter to Duncan in December 1863.

On September 29, 1864, Duncan was finally thrust into combat when Gen. Benjamin Butler assigned Duncan’s regiment to attack a Confederate fort at New Market Heights, Virginia. Butler had specifically chosen Duncan’s brigade and the 6th Brigade—both under Gen. Charles Paine’s command—for the New Market attack in order to demonstrate the capability and willingness of black troops to their many skeptics. At dawn Duncan attempted to surprise Confederate Gen. John Gregg and his 2,000 men, but swampy conditions and armed and waiting Confederates inflicted 452 casualties on Duncan’s troops and wounded him four times. Duncan’s men and the 6th Brigade did manage to capture New Market, but at a horrific cost.

Duncan recovered at Chesapeake General Hospital in Virginia. With a little creativity he was able to add some degree of comfort to his stay. He enjoyed delicacies such as “oysters, chickens, and pure sweet milk,” he wrote, that were brought into the hospital. Another recovering colonel “brought a cook along with him as a nurse, and she prepares our extras in fine style,” Duncan wrote to his mother eight days after New Market. “In this way we manage to get along nicely, in fact I verily believe that I am gaining flesh.”

He also proudly mentioned the achievements of his troops: “You will see that [the New York papers] all praise the Colored Troops of Genl. Paine’s command for what they did on the 29th.”

Duncan received honors for “gallant and meritorious service,” and the War Department awarded medals of honor to 14 black soldiers who served at New Market. Duncan recovered by February 1865. Writing from North East River Station, North Carolina, he sensed the impending end to four years of bloodshed. Duncan recounted a memorable passage through Wilmington, North Carolina, where the black population enthusiastically welcomed the Union soldiers.

“The slaves comprehend the great question at issue, and invariably assert that they would not fight for their masters, but are ready to fight on our side,” Duncan wrote. “I cannot see how the rebellion can long survive.”

Some say it was a “magnificent passion” that led to an alum’s exaggerated account of his role at Gettysburg.

Others say simply that he was absurd and reckless.

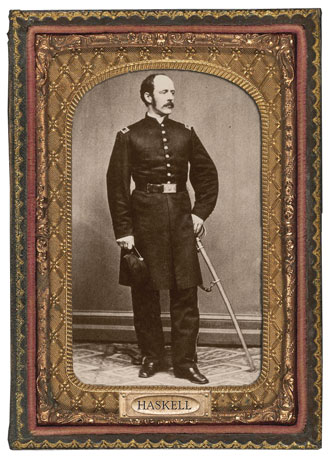

It is certain that Lt. Frank Aretas Haskell, class of 1854, fought at Gettysburg, in July 1863 with the 6th Wisconsin Infantry. Yet 46 years later his role in the battle—which had the largest number of casualties in the war—was the subject of a heated debate. Did Haskell ride solo along the enemy line of Gen. George Pickett’s charge of 12,000 Virginians while members of the 11th Corps of the Philadelphia brigade fled, as he claimed? Or was Haskell lying?

Originally from Tunbridge, Vermont, Haskell graduated with honors. He then moved to Madison, Wisconsin, where he joined the law firm of Orton, Atwood and Orton. He had a successful career practicing law until 1861, when the Civil War broke out. That June he was commissioned as first lieutenant of the first company of the 6th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry.

Leading up to Gettysburg, Haskell’s military service included battles at Gainesville, Bull Run, South Mountain, Antietam, Fredericksburg and Charlottesville. He was known for his “intelligence and courage, for his generosity of character and exquisite culture,” said Brig. Gen. Francis A. Walker of the Union Army of the Potomac, “long before the third day of Gettysburg.”

As many as 51,000 soldiers were ultimately killed, wounded or captured in the three days of fighting at Gettysburg as Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was driven out of the north. Two weeks after this bloodbath Haskell sent a long, detailed account of his role in the battle to his brother in Portage, Wisconsin. He didn’t intend the account to be made public, but his brother, impressed by the story, gave it to the editor of the weekly Portage State Register, who published it in a 72-page pamphlet.

Because of Haskell’s thorough descriptions of the battle, the pamphlet became popular among military experts and received literary praise. It was reprinted in 1898 with some omissions as part of the “Dartmouth College History of the Class of 1854” to no notable reaction. But when the Military Order of the Loyal Legion Commandery of Massachusetts and the Wisconsin History Commission republished the pamphlet in its entirety in 1908, the account was met with ire and contempt.

The Philadelphia Brigade Association—a veterans’ group for the Philadelphia Brigade—was so offended by Haskell’s unflattering portrayal that it published a pamphlet refuting his “malicious statements” in 1909—46 years after the battle.

The association acknowledged Haskell’s service as aide-de-camp on Maj. Gen. John Gibbon’s staff during Gettysburg and his continued service as colonel of the 36th Wisconsin Regiment in 1864. But “as a writer of events of the war he was absurd, reckless and unreliable,” the association charged. His “false and malevolent” stories were “unworthy of a class at Dartmouth College.”

Haskell’s account directly challenged the Philadelphia Brigade’s honor. He reported that members of the 11th Corps “sought to hide like rabbits” while he “ordered those men to ‘halt’ and ‘face about’ and ‘fire,’ and they heard my voice and gathered my meaning and obeyed my commands.” While the Philadelphians were allegedly fleeing Pickett’s men, Haskell wrote he was the “first mounting that stormy crest before the enemy, not forty yards away” and his was “the only horse there during the heat of that battle.” The Philadelphians rebutted this claim with sarcastic awe that Pickett’s men “who made such slaughter in OUR RANKS AT LONG RANGE could not kill first Lieutenant Frank Aretas Haskell.”

The problem with Haskell’s story, the brigade argued, was that it was “hastily written…between his hours of duty…while not yet fully recovered from the delirium of excitement that overcame him in the exalted position he claims to have assumed.” Haskell wrote that he was overcome by “magnificent passion” during the battle; the Philadelphians used this sentiment to discredit the account even though he wrote it two weeks after the battle, presumably having had time to cool off. They published the account of Col. Charles H. Banes of the Philadelphia Brigade as truth in a section of the pamphlet called “Banes versus Haskell.” The veterans praised the “calm, temperate, lucid, truthful and dignified statement” of Banes’ tales of the brigade’s bravery over Haskell’s words of disoriented passion.

The association accused any who published Haskell of being “vaccinated by the Haskell virus of vanity and venom,” and transmitting “the buffoonery of Haskell.” They requested the organizations publishing Haskell’s account to make a public disclaimer for its accuracy, otherwise the State of Wisconsin and the Loyal Legion of Massachusetts, “to say it very mildly, would be the reverse of creditable.”

The total killed, wounded and missing of the Philadelphia Brigade at Gettysburg was more than 32 percent, or about one soldier killed to every three engaged in battle. “Call you this ‘running like rabbits’?” the Philadelphians asked in their pamphlet.

Even a dear friend of Haskell’s asserted the dishonesty of his Gettysburg tale. Yates Selleck, a military agent for the State of Wisconsin, wrote into the public ledger of Philadelphia almost 50 years after Haskell’s death to correct his mistruths. “I was intimately acquainted with Haskell and had several conversations with him after the Battle of Gettysburg entirely in regard to that battle and I have good reason for stating that had Haskell survived until the close of that blood-stained chapter in our nation’s history, the tainted assertions contained in his personal diaries would, happily, never-never have been made public,” wrote Selleck. (Haskell was killed in action at Cold Harbor, Virginia, on June 3, 1864.)

Meanwhile, many generals had supported Haskell’s claims in their own reports on the battle. “When the contending forces were but fifty or sixty yards apart, believing that an example was necessary, and ready to sacrifice his life, [Haskell] rode between the contending lines with a view of giving encouragement to ours,” wrote Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock in his official report. General Gibbon wrote that Haskell “did more than any other one man to repulse Pickett’s assault at Gettysburg.”

Whether the Philadelphia Brigade Association was telling the truth or attempting to save face remains unknown. The real story rests with Haskell in his grave.

Additional reporting by Seymour Wheelock ’40.