“Anyone who tells you he can predict the future can’t predict the future,” says Joshua Kim, whose job as director of digital learning initiatives is planning Dartmouth’s online future.

Forewarned and yet undeterred, DAM set out to interview students, professors, and administrators about what the future might hold for the College. We asked, “What will Dartmouth be like 50 years from now, in 2069, on its 300th anniversary?” Questions ranged from the hyperlocal—will there still be an elm at the corner of North Main and Wheelock? (probably not)—to the existential—will there still be a Dartmouth? (highly likely).

Some of the predictions were grounded in science, some were educated guesses.

Pretty much everyone seems to agree that collaborative education is the future of undergraduate studies, although it’s hard to know what form that could take. The Dartmouth Applied Learning and Innovation (DALI) lab, which is a national model for educating undergraduates in tech design, has the feel of a Silicon Valley startup. Its teams of students have developed, among other things, virtual reality software for NASA astronauts. Though many say it has been their most exciting learning experience at Dartmouth—only 15 percent who apply are accepted—they get no academic credit. Rather, they are paid up to $15 an hour and, if they do poorly, instead of getting a D, they can be fired.

How the College will remake itself in the face of considerable institutional rigidity is murky. Barbara Will, associate dean of arts and humanities, doesn’t see a major restructuring. She thinks professors and deans are too protective of their own turf. “In the next couple of decades, I can’t see any departments we have willingly giving up their identities to merge or just say, ‘We’re just all Dartmouth professors,’ ” she says.

Seniors should have a particular stake in DAM’s question, since they’ll likely still be around. What do they hope to see when they return for their 50th reunion?

Shannon Rubin ’19 mentioned the bonfire, Lucy Tantum ’19, Winter Carnival.

“Lou’s!” says Marie-Capucine Pineau-Valencienne ’19.

What they won’t see, in all likelihood, is the towering 125-year-old elm at the corner of North Main and Wheelock. College arborist Brian Beaty expects it to be dead and gone by then. Age (elms usually don’t live past 175) or development (it was barely spared from a recent underground utility upgrade) could do it in. The spectacular fall foliage? Muted, as warming temperatures and bugs kill trees with the most colorful leaves—sugar maples, birches, and ashes. On the other hand, the magnificent elms along the Green that were ravaged by Dutch elm disease in the 1950s and 1960s have been replaced by a disease-resistant variety that should be 100 feet tall in the 2060s.

That fall, when alums return for Homecoming, football coach Buddy Teevens ’79 predicts there will be a game. He thinks kickoffs may be gone to reduce high-speed collisions that cause concussions and players may be required to stand upright in a two-point stance so they’re slower off the line (that’s not a misprint). But the game will still be recognizable as football.

At the 2018 World Economic Forum in Davos, Mary Flanagan, professor in digital humanities, asked fellow panelists, “What if we throw out the idea of university—I’m at a university, so apologies to Dartmouth—as a one-time thing.” Retraining would become the focus of higher education, not an afterthought, as people lose their jobs to robots and start over in the workplace, again and again.

David Kotz ’86, professor of computer science and former acting provost, thinks parking will be better.

In 50 years, current measures of diversity could be obsolete.

With the prevalence of international and mixed-race marriages increasing in this country, particularly among the well-educated, racial and ethnic diversity may no longer be as dominant an issue on campuses in two generations. But if economic disparities continue to widen, and the financial gap between scholarship and non-scholarship students continues to grow, income diversity could be the real flashpoint.

Organic chemistry, “Chem 51 and 52,” were the killer courses for premeds a half century ago. They remain so today, and by 2069, even as we colonize Mars, premeds could still be cramming for a quiz on the stereochemistry of alkanes and cycloalkanes.

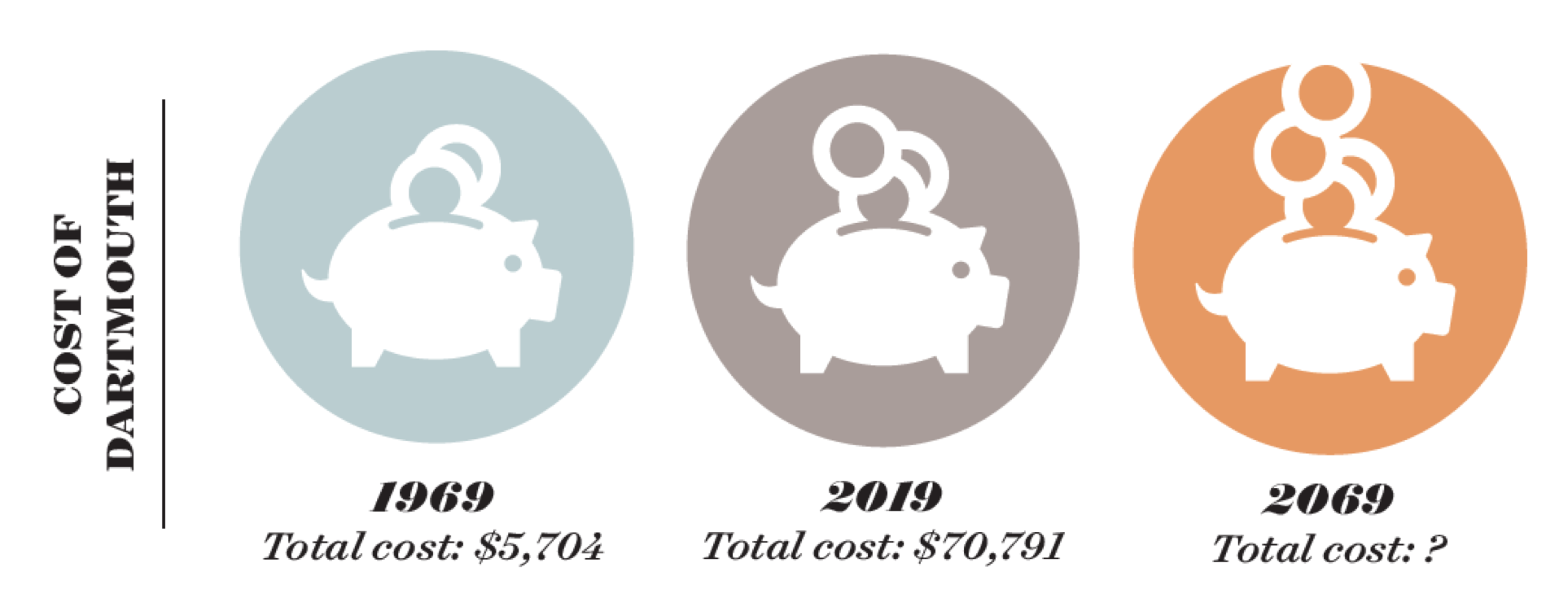

Of course, none of this may come to pass if the cost of a Dartmouth education continues to grow in the next 50 years at the pace it did during the previous 50. In 1969 tuition, room, and board came to $5,704. Today, with fees, it is $70,791. At this pace, in 2069 it will hit $1 million. Scholarships, which until now have served as a buffer for soaring costs, may not be able to keep up. Even with a $500,000 scholarship, who wants to take out a half-million-dollar loan?

No one we talked to had given much thought to whether Dartmouth will continue to exist as an elite college where gifted professors conduct important research and teach some of the brightest students anywhere. The presumption seems to be that, like England, there will always be a Dartmouth. As Lee Coffin, dean of admissions, says, “The centrality of the ‘Dartmouth experience’ does not feel like something that will ever be open to reinterpretation.”

A good reminder of how much could change in the next 50 years is to consider how much has changed in the last 50.

The short answer: an awful lot.

Whether driven by technology, scientific breakthroughs, civil rights, feminism, or governmental mandate—you never would have guessed most of it, a very humbling thought.

When Roger Sloboda is asked to name something he never envisioned as a new professor teaching biology in 1978, the first thing he does—even before mentioning gene modification or sequencing—is wiggle his smart phone in the air. “Exhibit A,” he says. “Who would have thought I could hold all the knowledge in the world in my hand?”

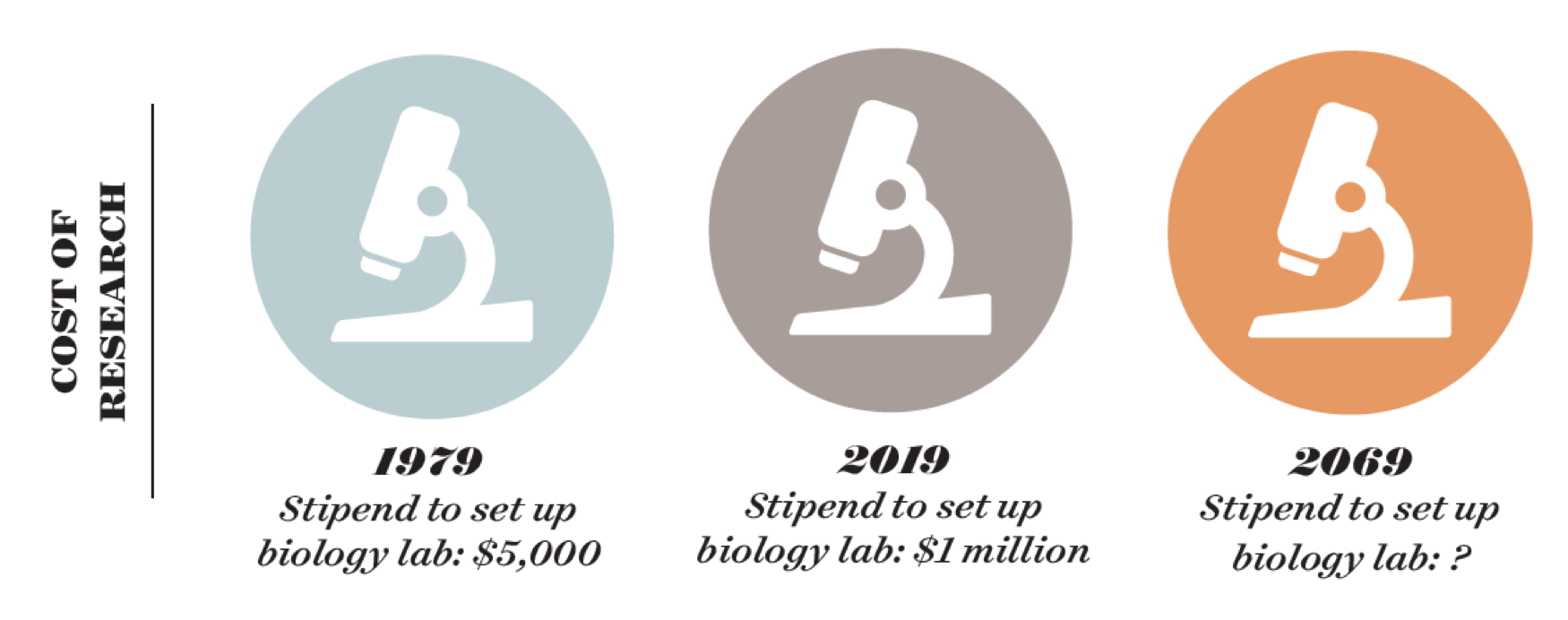

His Exhibit B was the astronomical cost of research today. When Sloboda arrived 40 years ago, he got a $5,000 stipend to set up his lab. Today new biology professors can get upwards of $1 million. A state-of-the art microscope is $400,000, a centrifuge $40,000. Chemicals, reagents, enzymes, antibodies, and tissue culture solution for a modest-sized laboratory can approach $100,000 per year. Even a month’s worth of mice can be $1,000.

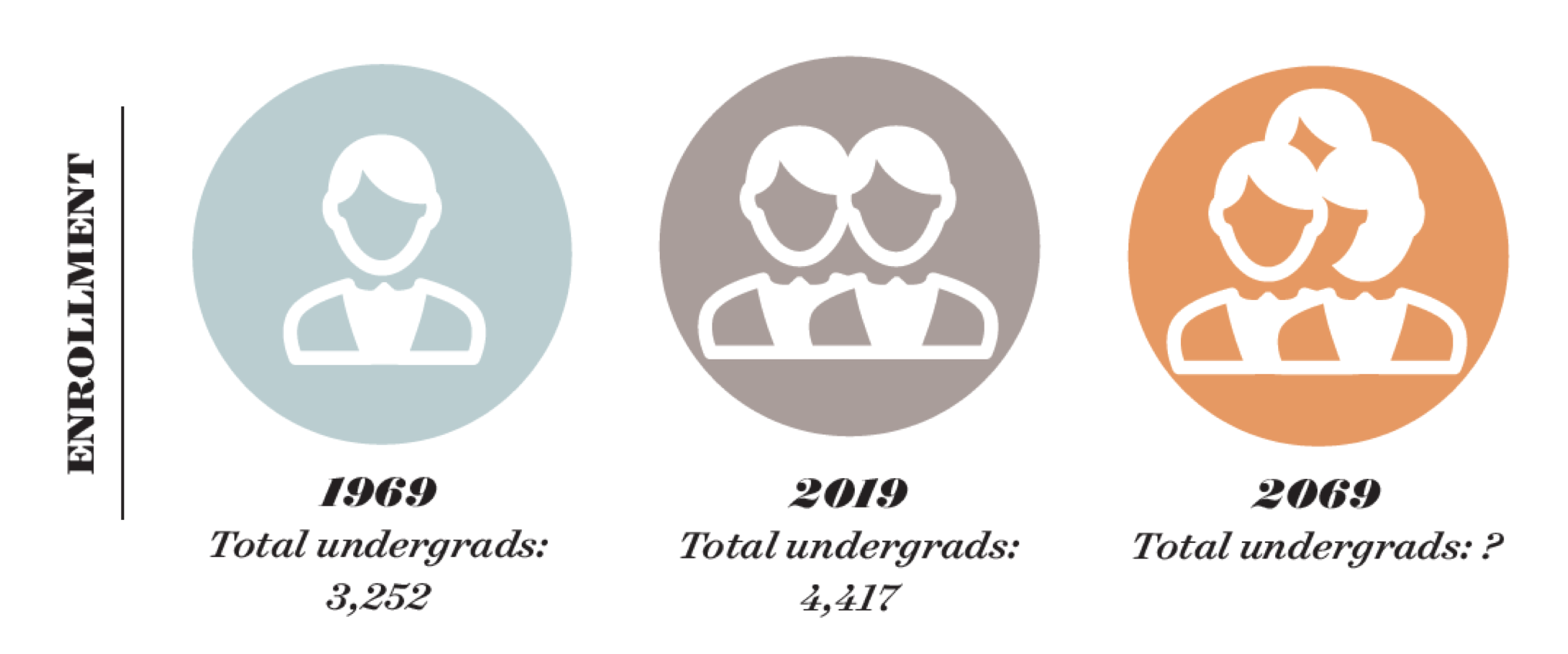

The face of the student body could hardly be more different than it was 50 years ago.

In 1969 a Dartmouth education was still for men only, though it was understood those days were numbered. At his 50th reunion that June, Dr. Robert M. Stecher, class of 1919, delivered a speech predicting how Dartmouth would change by 2019. “It will contain a substantial proportion of women,” he said. “That is threatening.”

Indeed, they landed in 1972. As Gina Barreca ’79 recounts in her memoir, Babes In Boyland, during those early days women were treated like curiosities unearthed during an archaeological dig. The male-female ratio was 5 to 1. The aptly named Professor Mann began every question to a female student with, “As a woman, what is your reading of the text?” So, Barreca says, she “started prefacing every answer with the phrase, ‘As a woman, I think Shakespeare means…’ or ‘As a woman, it strikes me that Tennyson’s point is….’ Among early Dartmouth women, it became a form of greeting. ‘As a woman, I think I’ll have the meatloaf for dinner.’ ”

In 2018, there were 2,251 men and 2,166 women.

The class of 1970 included 12 black men. By the class of 1973 there were 90, partly as a result of a recruitment program for “boys with underprivileged backgrounds.” Many of those black students benefited from the Alumni Fund, which that year financed 103 scholarships and 12 slide rules.

Though Dartmouth’s original mission was to educate Native Americans, as of 1969 only 19 had graduated. In the last 50 years the College has taken that mission to heart with 1,180 Native American graduates.

Of course, there is a difference between Dartmouth mandating change and campus culture changing. Bruce Duthu ’80, a professor of Native American studies, says when he was a student, “people had no compunction about coming up and saying, ‘How do you feel about taking the place of a better-qualified white guy?’ ” By the mid-90s, most of that was gone, he says. Even so, change is rarely ubiquitous or linear. While trustees abolished the use of the Indian mascot in 1974, online shoppers can still go to the Dartmouth Review website and purchase clothing with the logo, including a woman’s thong emblazoned with the Indian head.

In 1972 the federal government enacted Title IX, which requires that women have as many opportunities to play sports as men. Coach Teevens remembers its early years: “For the JV basketball program, women were recruited from the dining hall.”

Today, in accordance with the law, there are 18 women’s teams and 16 men’s teams.

Among the Ivies, only Columbia and Dartmouth have not had a female president.

What students major in is profoundly different. The study of the humanities, which for years has been in decline, was in full ascent 50 years ago. There were 31 faculty members in the English department and 28 in Romance languages and literature, compared with 25 in biology, 24 in math, and 18 in economics.

Last year 217 undergrads majored in the humanities, 541 in the sciences, 911 in the social sciences. There were 270 economics majors in 2017, compared with 46 English and creative writing majors.

College is often a place where an individual’s politics take root. Fifty years ago, the Baby Boomers protested the Vietnam War. Dozens of Dartmouth students, calling for the end of ROTC on campus, went to jail for occupying Parkhurst Hall. That June, John D.W. Beck ’69, a speaker at his Commencement, said the graduation robe “makes me feel like death and stagnancy” and urged classmates to remove theirs.

At graduation last June, many in the class of 1968, now in their 70s, wore white armbands, a protest aimed at President Donald Trump. “I was astonished not only by how many classmates wore the armbands, but also how quickly they put them on,” says Gerry Bell ’68, the 50th reunion chair. “You can take the boys out of the sixties, but you can’t take the sixties out of the boys. We still think we can change the world.”

And when the class of 2019 returns for its 50th? Taken as a whole, the students have not been the protestors that the ’69s were, though, according to The Dartmouth, at least 50 carpooled to Washington, D.C., to participate in the Women’s March in January 2017. There have also been “Take Back the Night” and “Black Lives Matter” protests on campus as well as support for the #MeToo movement—in November a group of women filed a $70-million lawsuit accusing three professors of sexual assault.

One of the most popular recent humanities courses, according to Will, was “The Sixties.” A harbinger of activism to come? Or a dose of nostalgia?

When it comes to the next 50 years, Professor Kotz is an inveterate optimist. He thinks parking will improve thanks to autonomous vehicles that will drive themselves to lots at the far reaches of campus. “The same way you hail a cab today, you will hail your own car. As you walk out the door, you’ll just say, ‘Come get me,’ and your car will drive up three minutes later to take you home.”

More than 10 percent of the core campus’ 269 acres is used for parking. If Kotz is correct, that could free 27 acres for other uses, including dorms to ease residential overcrowding.

But as Professor Sloboda points out, technological advances don’t necessarily translate into behavioral gains. The first day of introductory biology, almost every student brings a laptop for taking notes. Then he shows them a study that indicates students who have a laptop open during class retain 10 percent less information than those who do not.

“Next class, out of 50, I had one kid with a laptop,” he says.

How about an example of technology that enhances learning? “Fifty years from now, probably kids will put an electrode on their head, and I’ll push a button and zzzt, all the information will go in, and they’ll walk away happy,” says Sloboda. (He seemed to be joking).

In the next 50 years will Dartmouth have a female president? Among the Ivies, only Columbia and Dartmouth have not. Or perhaps a president who is African-American, Hispanic, or Native American?

In 2069 most courses may be taught using what is known pedagogically as the “flipped classroom” model. It is a more effective way of learning than the “classic classroom” model: Show up for a lecture in your pajama bottoms, borrow a friend’s notes, fall behind on the reading as you balance the demands of other courses, a busy social life, and much-needed sleep, then cram wildly at the end of the semester by pulling all-nighters. Finally, near death, emerge on the other end with a grade that won’t let your parents down.

The flipped model is being used for introductory courses such as “Bio 13,” which may have 50 or more students in a class. They watch videos of the prerecorded lectures before coming to class. They take online assessments that vary based on skill levels. When they arrive for class, the professor knows where the group, as a whole, stands, and where each student is. Class time is spent working in small groups guided by paid undergraduate teaching assistants. “The professor can walk around and work with individuals or groups of students,” says Kim, the digital director.

Guessing what the student body might look like in 50 years offers wildly divergent possibilities. One unknown factor is the outcome of the current trial in which Harvard is defending itself against allegations it discriminates against Asian-American applicants. The suit alleges that for years the university has rejected Asian Americans who are better qualified than some non-Asian students it has accepted, as measured by tests scores and grades.

Harvard counters that it relies on a holistic approach to admissions, with race as one consideration among many, in an effort to assemble a class that is also diverse economically, by gender and nationality, as well as a mix of student-scholars, scientists, artists, athletes, and legacies.

The Ivies, including Dartmouth, which has a freshman class that is 21 percent Asian-American, have filed a brief supporting Harvard. In contrast, for the last 20 years the University of California, Berkeley’s admissions office has relied heavily on test scores and grades, resulting in a student body that is about 45 percent Asian-American.

If Harvard loses, could Dartmouth look more like Berkeley? “It could,” says Coffin.

At the other end of the spectrum would be an admissions process so impacted by intermarriage that in 50 years, current measures of diversity could be obsolete. In 2002, fewer than 1 percent of Dartmouth students identified themselves as mixed race. Of this year’s freshman class, 7 percent do, compared with 4 percent Native American, 9 percent black, and 12 percent Latino. The trend is national. According to the Pew Research Center, the share of recently married blacks with a spouse of a different race or ethnicity is 18 percent. It’s 27 percent for Hispanics and 29 percent for Asians. Among newlyweds who have bachelor’s degrees, 20 percent of men and 18 percent of women were intermarried.

Coffin says racial diversity will remain “critically relevant,” but adds that “there will be a continuing reimagining of how we see ourselves.” He tells a story from his time in admissions at Tufts, about a pair of Dominican-American twins. One checked the boxes on the admissions application indicating she was Dominican and black, the other marked Dominican and Hispanic. One was referred to the black cultural center, the other to the Hispanic center. “They called and said, ‘How is it possible these twin sisters are on two different lists?’ I said they answered the questions in their own way.”

Duthu, a member of the Houma tribe, sees the same issues among Native Americans. “This idea of Noah’s Ark—we need two of these, two of those—may seem like a weird, archaic system.” Fifty years from now, could there be legal battles over who’s Native enough to qualify for a Dartmouth education? “It’s a very volatile kind of situation. I have no idea how that will work out,” says Duthu. Much can be at stake. Some tribes that operate casinos have fought protracted legal battles with millions of dollars in the balance over whether an individual has enough of a tribal lineage to share profits.

During an interview at the Hanover Inn, sitting among alums and parents checking in, Shannon Rubin ’19 points out something you almost never hear: “They always say half of Dartmouth students get scholarships, but that means half don’t and come from families that can afford to pay $70,000 a year.”

The higher costs go, the wealthier a family has to be to afford the full freight, and the greater the divide between scholarship and non-scholarship students.

In 1970 annual costs at Dartmouth were about $5,700. Families with two working parents—a school secretary and newspaper copy editor, for example—could send a child to college without a scholarship. Today that middle-class kid would need a major scholarship.

“At some point in the next decade or so, Dartmouth and our peers will likely cost roughly $100,000 a year,” says Coffin. “That will be a staggering data point.”

Is there anything that might reverse the spiraling upward costs in the next 50 years?

Higher ed is caught up in an arms race over salaries and facilities. In 2011 the biology department moved into the Life Sciences Center, an award-winning, state-of-the-art, energy-efficient building that cost $90 million. Could Sloboda still be doing his work in the old building? “It probably could have been modified, yes,” he says. “But if we’re recruiting a new faculty person, and we showed them a lab in a cement-block building and another university had state-of-the-art laboratories? It’s part of playing the game.”

Several professors complain that too many administrators are paid too much. “The president gets a million dollars, Rick Mills, his executive vice president, and the provost make something like $700,000 each,” says Sloboda. “These are huge salaries, and if they keep going up it’s going to be a huge, huge part of the budget.”

According to the College’s 2015 tax return, the latest publicly available, then-provost Carolyn Dever earned $783,890, Mills earned $660,089, and President Philip Hanlon ’77, $1.25 million. Sound like a lot? The presidents of Brown, Columbia, and UPenn make, respectively, $1.28 million, $2.5 million, and $3.5 million.

One Dartmouth administrator suggests that dramatically cutting costs would mean hiring fewer tenured professors and more adjuncts. The average tenured professor at Dartmouth, who has a guaranteed job for life and gets a paid year off every seven years for sabbatical, makes $248,000, according to the American Association of University Professors. That lags behind UPenn professors ($281,000 average), Columbia ($306,000), and Princeton ($307,000). The more colleges spend to attract the best, the more they have to spend to attract the best. “That’s the wicked spiral of higher education,” says Coffin.

Still another contributor to the wicked spiral is the penchant for adding without subtracting: Although new educational fields are continually being added to keep up with societal changes, rarely is an academic department shut down.

“There’s a lot of inertia,” says Kotz.

Will agrees. She says that while there’s an ongoing turnover from retirement, “tenure can create a certain kind of sclerosis. Russian studies is a small department, they just made a few really good hires. They are going to want to hang on to their departmental status for as long as possible, in part because if they lose their department, they won’t have the visibility on campus that would allow them to contribute to hiring decisions.”

As for cutting costs, invariably the first words out of the experts’ mouths are “remote learning,” meaning online lectures and exams.

Dartmouth, like most elite colleges, has resisted the idea when it comes to undergraduates, but in recent years it has developed two largely online, 18-month master’s programs, in healthcare delivery sciences and public health. The model differs from most online programs. The master’s in healthcare delivery requires enrollees to spend six weeks on campus spread across four visits. There are online seminar discussions, virtual one-on-one office hours, and collaborative group projects. Courses are taught by the same Dartmouth professors who teach on campus.

“We worked to ensure it’s premium quality, like everything at Dartmouth,” says Kim, the digital director. That includes premium prices—total cost for the master’s program in healthcare delivery for the class of 2020 is $108,375, about the same as for the traditional master’s candidate. So in terms of cost, remote learning at Dartmouth in its present form is part of the problem, not the solution.

There is one blip. Last September the University of Pennsylvania announced that next fall it will offer an online bachelor’s for a four-year tuition cost of about $75,000—approximately one-fourth the cost of a Dartmouth degree. To date, undergraduate education at Dartmouth has been exclusively campus-based. Could that change? “It’s possible,” Kotz says. “I have to be very careful with my provost hat on.”

The most discussed academic trend during the last decades has been the dramatic drop in students studying arts and humanities. Dartmouth is no exception. In 2008, just as the Great Recession hit, there were 448 humanities majors. By 2016, with students—and parents—still traumatized about the job market, that fell to a then modern low of 256.

Whither the humanities? Or perhaps, wither the humanities?

Will is optimistic, even though the number of humanities majors dropped from 291 in 2017 to 217 in 2018. She says that scandals involving Facebook and Twitter may dampen enthusiasm for science, tech, engineering, and math (STEM) courses. “The STEM bubble may be bursting a little bit,” she says. “The bad publicity around Silicon Valley hubris has been good for the humanities.” Indeed, science majors fell from 595 in 2017 to 541 in 2018.

She believes there’s been a shift in the type of student being admitted since Hanlon became president in 2013 and brought in Coffin in 2016 as admissions director. “Phil immediately started to address Dartmouth’s Animal House reputation with a series of important measures,” says Will, who chaired Hanlon’s 2014 Moving Dartmouth Forward committee that, among other suggestions, recommended the campus hard liquor ban that went into effect the following year. Indeed, the percentage of 2018 freshmen interested in the humanities rose to 14 percent from 10 percent in 2013, according to admissions dean Coffin.

The numbers Will cites are minuscule in the context of a 50-year timeframe, but she has history on her side. For more than two centuries, Ivy League students studied the liberal arts and went into the world to learn their craft. For example, Dartmouth has never offered a major in journalism. Students learn at the College paper and through internships.

Chances are that any new academic majors will be built around newly hired professors. A prime example is digital humanities, a young discipline still taking root at Dartmouth. It involves, among other things, the study of computer code and the development of video games that teach worthy human values—such as protecting the environment, inspiring girls to study science, and encouraging vaccinations. It sounds like fluff, but it requires considerable academic rigor. How do you determine that kids are learning what a game purports to teach? The games created need to be fun, but the research indicates that if kids know they’re good for them, the games won’t be as effective. For example, Awkward Moment, which was originally developed at Dartmouth, is sold in the games department at Barnes & Noble—not the educational department.

Professor Mary Flanagan pretty much invented digital humanities as an academic discipline. At the University of Buffalo in 1999, with a $200,000 National Science Foundation grant, she created The Adventures of Josie True, a video game aimed at encouraging girls to go into STEM fields. Next stop was Hunter College, where she started Tiltfactor, a research lab that designs games to promote learning as well as changes in attitude and behavior. After Dartmouth won a $10-million grant from the Sherman Douglas Foundation in 2005 to endow two professorships in “emerging fields in the faculty of arts and sciences,” Flanagan was hired and brought the Tiltfactor lab with her in 2008.

For students, there’s excitement in being present when something new takes shape. At first, Flanagan’s Tiltfactor team designed games that it assumed had a positive impact, but didn’t have proof. With guidance from researchers at the Dartmouth Institute, the team devised behavioral studies to compare attitudes of schoolchildren who hadn’t played the game with those who had. In this manner, the team discovered that its game Pox—in which characters who are not vaccinated die—was not as effective as the Zombie Pox version, where the unvaccinated turn into zombies. “Zombies made players more empathetic,” says Max Seidman ’12, a lab project manager.

At present there is no major—Flanagan teaches in the film studies department. But in recent years funding has been allocated to hire three new faculty members in the digital humanities.

A student at the DALI lab makes the most compelling argument for why Dartmouth in 2069 will still be Dartmouth, why a Dartmouth education will still count for a lot, why remote education cannot replace it, and why students will still journey to Hanover to learn from great professors and each other and to socialize and waste time together.

“Collaborative learning” was the short answer from John Kotz ’19 (son of David). At the DALI lab teams work on extraordinary projects, such as the $1.2-million NASA grant the lab shared with the Geisel School of Medicine to develop virtual reality software that reduces astronaut anxiety during lengthy space missions. Astronauts can put on a virtual reality headset and for a half hour be “transported” back to earth, perhaps to sit on a park bench and observe life going by or view a mountain stream or watch puppies at play.

For another project, students built a functioning desktop computer mounted on a board 2 feet tall and 3 feet wide and framed with plexiglass, with each component separated so it could be clearly identified and the circuitry illuminated by flashing colored lights.

It is beautiful to behold, and far more powerful than an ordinary laptop—it can run virtual reality experiences and be used in interactive touch-screen demonstrations of projects. No one had assigned the project. It was just an idea some of the students found interesting.

“Completely out of the blue we wanted it to happen, so it happened,” says Kotz. It would not have happened online, he says. “When you’re added to a group online—say you’re in a Facebook messenger group—it’s easy for you to step back and let other people speak. When someone has an idea, you’re not necessarily responding to say, ‘Okay, how can I improve this idea?’ It’s the serendipity and the physicality of us all being here. Like I would pass Adam Rinehouse ’19 or Ben Cooper ’18—they helped design this. I would be walking around campus, and I was like, ‘Hey, have you thought any more about this project?’ Some of the coolest ideas I’ve had have just been random exchanges that happen in person. I don’t believe major innovation can happen without it.”

Toward the end of the project, when it was time to mount the computer, about a dozen students showed up and helped them finish the job in just two hours. Asked who had the original idea to build it, Kotz says he couldn’t remember. “And I don’t want to remember because, honestly, the coolest thing about it was that we all germinated in our own minds together.”

Michael Winerip is a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter. In his 30-plus years at The New York Times, he was a staff writer, national political correspondent, investigative reporter, and education columnist.