Happenstance led to the pivotal career moment of Crew. The scientist bumped into the leader of the Event Horizon Telescope Project while walking down an MIT hallway. The director needed someone with Crew’s one-of-a-kind computer skills to help his team photograph M87, a massive black hole 55 million light years away at the center of the Messier 87 galaxy.

It was a tall order that, if done successfully, would open up a new era in astrophysics. No one had ever been able to photograph a black hole, one of the universe’s most mysterious objects.

Crew designed, tested, and operated computer systems that converted M87’s radio signals into data that could be analyzed to produce the image. Instead of using one telescope, Crew relied on radio telescopes in Hawaii, Antarctica, and elsewhere to ensure the best resolution. “It was like seeing a tennis ball on the moon or sitting in New York and reading the menu in Paris,” he says of the telescopes’ collective power.

He still remembers the day he finally glimpsed the black hole on a colleague’s computer screen. As he stared at the image, which resembled a fluorescent orange donut, he thought about all the science, technology, and human effort that made it happen. “The most surprising thing to me about this whole process is that our little image showed up in newspapers all over the world,” says Crew, who was one of the first to view M87 in 2018.

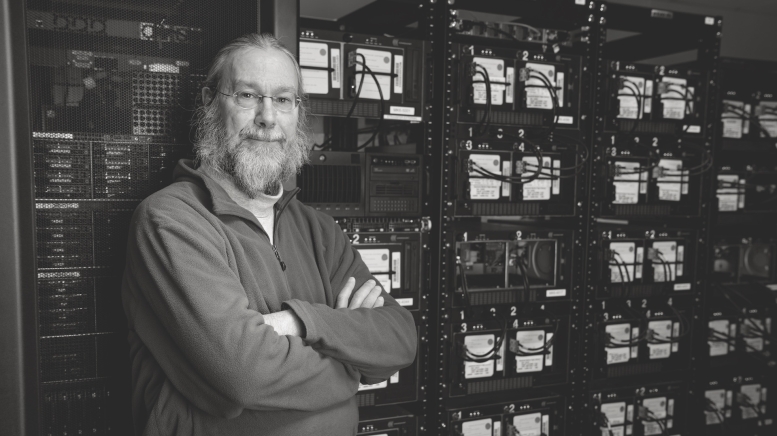

With his rimless spectacles and a thick gray beard—think Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings—Crew looks every bit the physics and math double-major he was. His thesis tackled plasma physics, and he worked under professor John Walsh. Many nights found him outdoors under the stars. He relishes memories of looking up into Hanover’s “absolutely glorious” unpolluted night sky.

After graduation Crew earned his Ph.D. in physics at MIT. He later studied the sun’s solar wind and analyzed data from NASA’s Interstellar Boundary Explorer, a satellite that is now mapping the sky.

Today Crew spends much of his time at an observatory in Chile, where he’s laying the groundwork for more black hole data collection in 2020.

“Time flies when you’re having fun,” he says.