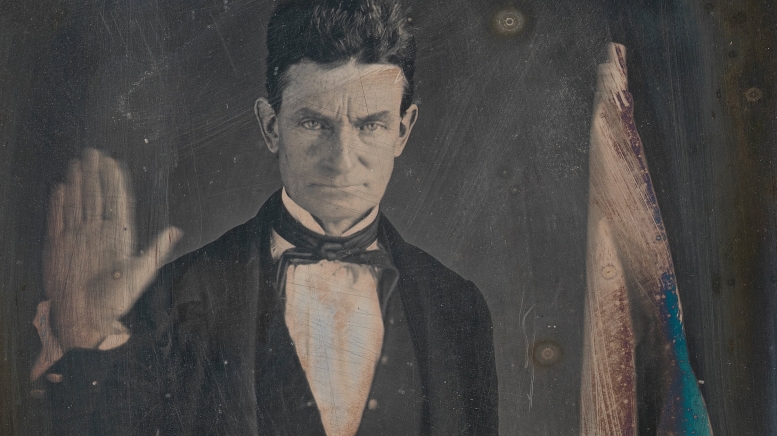

John Brown stares stern-faced, his expression uncompromising, out of a 4.25-by-3.25-inch black-and-white daguerreotype, one hand raised as if taking an oath, while his other clutches a flag. The tiny portrait is framed in brass and enclosed in a leather case with silk lining impressed with the name of the photographer’s studio.

The earliest known image of the radical abolitionist, it may also be the oldest surviving product of Augustus Washington’s portrait studio. Made circa 1847, the same year Washington was set to have graduated from Dartmouth, the image took about seven seconds of exposure to create, during which time Brown likely kept still by leaning against a brace.

“It’s a riveting image,” says Ann Shumard, a senior curator at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., and an expert on Washington’s life and work. The pose and composition of this portrait required an artist’s eye, according to Shumard. “In terms of the spirit of this photograph and its symbolic power it’s quite remarkable,” she says.

Even more remarkable is that Washington, the son of a South Asian immigrant and a former Virginia slave, was able to make a name for himself in the photography business in the first place. Born in Trenton, New Jersey, in 1820 or 1821, when it was illegal in many states to teach even free African Americans to read and write, Washington pursued an education in the face of intense racial polarization. His early academic promise prompted him to organize a school where, as a teenager, he served as a teacher for other black students in Trenton. This fueled his determination, as he would later write, to become “a scholar, a teacher and a useful man.” He taught and studied at several schools throughout the Northeast before he matriculated at the College in 1843 as its only black student.

He quickly found himself burdened with accumulating debt. Although some of the mentors he acquired at previous institutions and from abolitionist communities he had been involved with made modest contributions, they were not enough to cover his expenses. Unable to find a school in the Upper Valley that was willing to hire a black instructor, his previous means of earning money, Washington turned to photography to help pay his tuition bills.

“Daguerreotype offered Washington the opportunity to make good money off of what was a pretty modest investment,” Shumard says. “There was a huge demand for these images.” It is unknown how he learned his craft, but Hanover townspeople and Dartmouth faculty alike sat for his camera.

Perhaps weary from dealing with the pro-slavery attitude of College President Nathan Lord, Washington left Dartmouth at the end of his freshmen year, still owing the College money. He found work in Hartford, Connecticut, as a teacher at the North African School for black students, and within a year had earned enough to repay all but a few dollars of his debt to Dartmouth.

That he left many of his belongings, including his daguerreotype equipment, at the College indicates he intended to return. But by 1846 he had sent for the equipment and was advertising his portraiture services in the pages of Connecticut’s anti-slavery newspapers. By 1850 Washington was financially secure enough to marry, but his personal fortunes and accomplishments were severely undermined that same year by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, a draconian measure that called into question the liberty of black Americans, including those who had been born into freedom. Suddenly vulnerable to detention as a presumed slave, Washington set his sights on emigration.

Within three years of declaring in an 1851 op-ed in The New York Daily Tribune that Liberia was the last hope for black Americans in search of freedom, Washington had raised enough funds—by aggressively soliciting new clients to sit for portraits—to move with his wife and their two small children across the Atlantic. They were settled in Monrovia by December of 1853, and Washington wasted no time establishing himself as Liberia’s foremost photographer.

Using the funds he generated from photographing elite clients such as the nation’s president and vice president, Washington invested in real estate and eventually came to own several stores, factories and one of the most successful sugar cane growing operations in the nation. The acclaim he gained as a successful entrepreneur eventually landed him a seat in the Liberian Senate.

Some time before 1860, when the revenue from his portraits was no longer necessary to fund his other enterprises, Washington put his camera aside. Ironically, after more than a decade of photographing others, Washington doesn’t seem to have sat for any portraits himself. He remained devoted to Liberia as “the last refuge for the oppressed colored man” until he died there in 1875.