Bring on The Heathens

The Band of Heathens takes the stage at the Mile 0 Fest in Key West, Florida, like they are coming up for air. It’s the last day in April, 2021, and the Austin, Texas-bred roots-rock band hasn’t performed for a full-blown live audience in 14 months. For this performance—the first of two they’ll do at the festival—they’re playing on a temporary beachfront stage under the afternoon sun. The crowd isn’t huge, but it’s dedicated. Mile Zero is among the first American music festivals to test the receding waters of the Covid pandemic. For bands and fans alike, it’s a chance to reconnect. Rolling Stone calls the Heathens “a smoking live band,” and the group has toured relentlessly for 15 years, playing everywhere from small clubs to huge festivals. Along the way, they’ve built up a particularly intense following. “These cats are why I’m here,” one fan tells me.

The five-piece band launches into a mix of familiar favorites—goosebump-raising harmonies on “Hurricane,” psychedelic twang on “LA County Blues”—and some tunes from their latest album, Stranger, which they recorded in the depths of the pandemic. (It’s the band’s sixth studio album and 11th full-length record overall.) “It feels so good to be together again,” lead singer and guitarist Gordy Quist ’02 tells the crowd. “It seems like it’s been a whole year of shows getting pushed back three months and then another three months. So thank you all for doing this thing with us!” A cheer goes up and a few dozen beer bottles are raised aloft in salute.

After the set there’s time for autographs and selfies with fans. One longtime follower hands Quist a case of wine he’s brought as a gift. (“He does this a lot,” Quist tells me later. “It’s always amazing.”) Then everyone piles into a van for the trip back to their hotel. I find a seat in the rear next to keyboard player Trevor Nealon ’02. The band members briefly discuss the performance, but then talk turns to another matter of importance: the vicissitudes of soccer-practice carpooling. Quist and Nealon are both fathers, each with two young daughters. Youth soccer is a major preoccupation in their circle. Quist recounts how a mutual friend recently offered to bring his daughter home from practice—on the back of his Vespa motor scooter. “I was like, she’s only 6 years old,” Quist says. “She still needs a booster seat.”

It’s not exactly the kind of banter one expects from seasoned rock and rollers back out on the road for the first time in more than a year. For Quist and Nealon, though, defying stereotypes is a lifelong habit. The two met more than two decades ago, not in a recording studio or Texas roadhouse, but on a recruiting trip organized by the Dartmouth football team. “We just kind of vibed,” Nealon recalls. Both had played quarterback on their high school teams, Quist in a Houston suburb, and Nealon in Tacoma, Washington. Both were musicians: Guitarist Quist had fronted rock bands since middle school, piano player Nealon leaned toward jazz and the Grateful Dead. Both enrolled and suited up for football in the fall. “I think the musicians on campus probably thought we were tool football players,” Quist says. “And the football players thought we were weirdo musicians.”

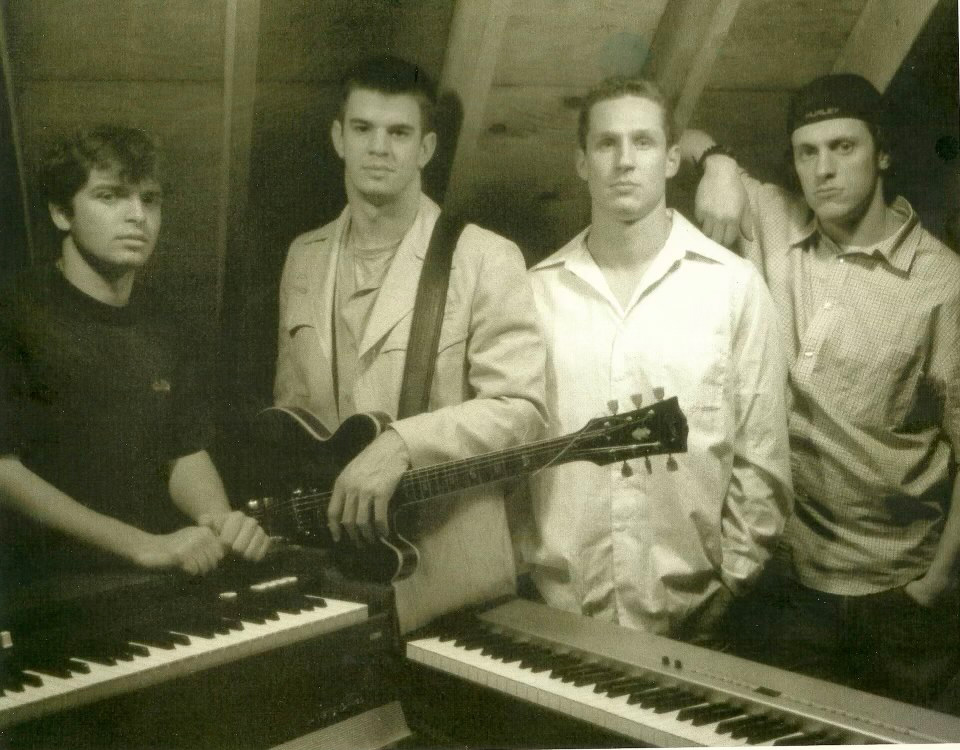

Key West’s ubiquitous semi-wild chickens are pecking and crowing outside Quist’s ground-floor hotel room. The embroidered jumpsuit he’ll wear for the next night’s performance is draped over a chair. The wine is on the dresser. We start off talking about that first semester at Dartmouth. Nealon remembers a night—before classes even began—when he sat down at a piano in some dorm basement and started to play. Quist walked by and nodded. “A few minutes later he came back with his guitar and just started picking,” Nealon says. That’s how it began. By the end of the year the two freshmen, along with teammate Damien Roomets ’02 (wide receiver, bass guitar), had joined a band.

Before long they’d joined a fraternity as well, the football-centric Gamma Delta Chi, naturally. There they appropriated a common room as their rehearsal space. (“It was supposed to be the library,” Nealon laughs.) Their ever-evolving ensemble had various names—Funk Barnacle and the Sea Biscuit Bunch was one—before settling on Lucky Southern. They mostly played fraternity dances and the Lone Pine Tavern at Collis. “It was just a party band,” Quist says. “We played whatever kept people dancing: Stevie Wonder, Joe Walsh…” “…Guns N’ Roses, Aerosmith, Phish,” Nealon continues. “Gordy comes from Texas and had a Fender Strat, so we did some Stevie Ray Vaughan.” The band was just “a fun release,” both insist. But Quist’s freshman roommate, future U.S. Ski Team downhill star Bryon Friedman ’02, says Lucky Southern—featuring those three powerful football players—made a big impression on audiences. “These guys were jacked,” he says, “Gordy must have weighed 225, pure muscle. But here they were on stage just being so playful and fun. You hear the Heathens today and you hear strong Southern-rock-meets-singer-songwriter roots. But back then those guys were more of a jam band.”

Still, it was sports, not music, that ruled their lives. “Football was all consuming,” Quist says, even in the off-season. In 1998, when the two players were recruited, the Dartmouth team was coming off two spectacular seasons. But during their freshman year it all fell apart. Coach John Lyons had passed his peak with the team and the next few seasons were brutal. “We lost every way imaginable,” Nealon says. “It rips a little of your soul out every time.” Nealon played cornerback and Quist was a linebacker. They stuck it out through four years of defeats and injuries, including a shattered finger for Quist—a particularly scary fracture for a guitar player. Both musicians say the experience taught them the importance of grit, and both mention the lifelong friendships forged by football. “Despite everything I look back on it with fond memories,” Nealon says.

Nealon majored in government. Quist pursued economics, though he had more passion for religion, especially his classes with that department’s iconic professor, Charles Stinson. Both assumed they would wind up working in the financial industry. “Ivy League athletics is a huge pipeline into Wall Street,” Nealon says. “There was just an expectation that you would go into that field.”

Meanwhile, their musical lives were growing richer. “I learned so much about music in those years,” Quist says. “People around me were speaking in ones and fours and flat sevenths,” he says. “I knew I had to learn that language if I was going to keep up.” A class in jazz improvisation helped, he says. But Lucky Southern’s members mostly learned from each other. The discipline they brought to football also applied to mastering songs and building their chops. “When you go to school with a bunch of driven overachievers, the term ‘self-taught’ can mean something pretty advanced,” Quist says.

During senior year everything changed. The 9/11 attacks cast a pall over the campus. Then the ensuing economic downturn put prospects for post-graduation finance jobs in doubt. For many football players, the end of the senior fall season can also trigger a kind of identity crisis. “You realize, okay, this stage of my life is over,” Quist says. “You kind of have to figure out who you are outside of this thing that you’ve been doing so intensely for many years.” Some of his teammates struggled, he says. But Quist, Nealon, and Roomets already had a different identity to embrace: “Come winter and spring semesters, we were musicians.”

With football over, Lucky Southern slipped into a higher gear. Members even found time to record an album, driving down to a Boston recording studio on weekends. Still, with graduation looming, they had to start planning their post-college lives. “Nobody was hiring, which was fine by me,” Nealon says. “So we thought, let’s just keep the band going!” Lucky Southern drummer Fred Carleton ’04 was from Cape Cod, Massachusetts. He convinced his parents to let the band move in for a few months. The group spent the summer playing bars up and down the Cape. “That was my first taste of being a professional musician,” Nealon says. “After Labor Day we all said, ‘Now what?’ ”

Quist and Nealon figured it was time to grow up. At least so they thought. They splurged on a last-hurrah trip to Europe—“the whole Eurail Pass thing,” Nealon says—and then Quist moved to Houston, taking a job as an analyst for Lehman Brothers. Nealon wound up in San Francisco working in sales for a financial services company. “Within six months we both knew we had to get out,” he says. Through it all Quist kept working on his songwriting, playing coffeehouses in the evenings, jotting down lyrics in his cubicle by day. “I used to keep a spreadsheet ready to hide my notebook in case someone walked by,” he laughs. Quist and Nealon would talk on the phone at night, planning their escape. “It was just a foregone conclusion: We had to move to Austin,” Nealon says. The minute Quist’s year-end bonus hit his bank account, he gave his notice. His supervisors assumed he’d return in a year or two, begging for his old job back. “When I quit the banking industry to move to Austin, who would have predicted that Lehman Brothers would go broke before I did?” he says.

At the time Austin was perhaps the most exciting city in the country for up-and-coming artists, especially those tapping into the roots of American music—folk, country, blues, rockabilly—a wide open genre that was starting to become known as “Americana.” Nealon and Quist often played together in those years, but they also found their own musical orbits. Local artists started calling Nealon when they needed an ace keyboard player. Quist began to bond with other singer-songwriters, in particular a tall, powerful singer from Boston named Ed Jurdi. The two began sharing the bill at an Austin nightspot with a third singer. They soon realized they liked performing together, and in 2005 the Band of Heathens was born.

The Heathens blew up fast over the next few years, winning awards and playing the Austin City Limits TV show. Nealon joined the group on stage and in the studio when he was available. But then he decided to take a break from Austin, moving to Park City, Utah, where he played in a band with Roomets, his former teammate. That band, Wisebird, was a local success—and Nealon experienced “one record powder season”—but he knew the best opportunities were back in Austin. By the time he returned, the Band of Heathens had built a national presence. And they really needed a full-time keyboard player.

Watching the Band of Heathens on stage, it’s hard to imagine any job could be as much fun as this. It’s the last night of the Mile 0 festival, and the band is arrayed across the enormous stage of Key West’s outdoor amphitheater. “Y’all ready for liftoff?” Quist shouts, and hundreds of fans begin surging forward. You can see why their friend Bryon Friedman calls the Heathens “a well-oiled, finely tuned rock and roll machine.” Quist and Jurdi lean into dueling guitar solos in timeless Southern-rock style. Behind his banks of keyboards, Nealon stirs up aural concoctions like a mad scientist. All five Heathens chime in on delicate harmonies that owe as much to bluegrass as to rock. When the band drops into the a cappella chorus on “Hurricane”—“I was born in the rain on the Pontchartrain…”—a thousand voices sing along and a thousand beer cups levitate into the evening sky.

As fun as it might be, the music business is still a business, and the band takes that side of it seriously. “I keep my Excel skills from my banking days pretty sharp,” Quist says. Despite several offers, the group long ago decided not to sign with a record label. To fund their first studio album, members solicited loans from friends and fans, an early version of the kind of crowdfunding that platforms such as Patreon would later digitize. “We had a whole business plan,” Quist recalls. The plan worked and all their investors got paid back—with interest. The Alternate Root, an online music journal, wrote, “The Band of Heathens epitomize Indie, building their band business from the ground up and keeping everything in-house.”

The group’s members never expected to be ultra-wealthy, but they didn’t want to play for tips at coffeehouses either. Quist sees the band as part of “a strong middle class of artists who have figured out how to make it work as a steady job.” Of course, at a time when CD sales are a fading memory—and the revenues artists earn from streaming services are scandalously low—the band’s main paycheck is still earned on the road.

With the exception of a few aging arena rockers, touring in a rock band is typically a young person’s game. Grinding from city to city in a van is one thing when you’re in your 20s; it’s something very different when you have marriages, kids, and mortgages to maintain. How do they keep it all going? “We all married well,” Nealon says matter-of-factly. “Our wives are a very important part of the whole thing.” (Quist calls his wife, Amber, “the true rock star of the family.”) In earlier years the Heathens performed more than 200 shows annually. “It was unsustainable,” Quist admits. These days, he says, they try to keep it to about 100 shows a year. “It’s all about finding the balance.”

Living in Austin helps. The thriving local music scene means plenty of side gigs for both musicians. Nealon often gets tapped to record or perform with Austin legends such as Bruce Robison and Kelly Willis. “When I’m doing session work, I can still be home for dinner,” he says. Quist co-owns a local recording studio where he engineers and produces recordings for other musicians, including Jordan Matthew Young, a recent finalist on The Voice.

The pandemic threw a wrench into these finely tuned lives. “We had all these gigs lined up and they just started disappearing one by one,” Nealon recalls. So the band pivoted. If the Heathens couldn’t tour, it would reach out to its audience digitally. They set up a weekly livestream—no small feat, considering that, aside from Nealon and Quist, the group’s members now live in several states. The band couldn’t really play live as a whole, but they pieced together clever music videos, showcased songs different members were working on, and told stories. “It was more personal than what we normally do, playing rock and roll on a stage,” Nealon says. Meanwhile, hundreds of fans chipped in small donations and chatted—with the band and among themselves. “We were shocked by our core music family’s support for us, their generosity,” Quist says.

“This pandemic has been devastating in so many ways,” he adds, “but it also opened up doors for connection with our fanbase that we never imagined.” Inspired by the reaction to its weekly livestream, the band is launching the Good Time Supper Club, a multitier subscription service via Patreon that will offer behind-the-scenes glimpses into its creative process. “The goal is that people should feel they’re getting back way more than they’re putting in,” Quist says. “We give people our music, that’s our job,” he adds. “And it’s really cool what people give back out of appreciation”—Quist and Nealon both glance over at the cardboard box on the dresser and laugh—“especially when it’s good wine.”

It’s obvious both musicians are quietly thrilled to be playing honest-to-God live shows again. It’s not just the reliable paycheck—or the wine, for that matter. It’s also the sense of communion with their audience and with each other. “The pandemic is the longest I’ve ever gone without plugging in an electric guitar and playing rock and roll with other people in the same room,” Quist says. “I remember when I was 13 years old and my buddy had a drum kit. I went to his house with my little Peavey amp and I plugged in to play with another person for the very first time. I’ve never forgotten that surge of energy. Every time I go on stage I’m chasing that adolescent feeling of rock and roll.”

The Key West roosters are still crowing when I gather my things to leave Quist’s hotel room. As I slip out I hear the two of them discussing plans for the evening. “Have you got a corkscrew?”

James B. Meigs is the former editor of Popular Mechanics and other magazines. A harmonica player, he toured with the Americana band Spuyten Duyvil for 10 years.