Overboard

At first, the rapids seemed routine.

Rough water was nothing new for the paddlers, who were more than two months and 550 miles into a long-distance haul through remote rivers near the Arctic Circle. On this September day in 1955 a little froth wasn’t going to force the six-person crew to pull out their canoes and carry them instead.

But within hours expedition leader Arthur Moffatt ’41 was dead. Waves that looked small turned out to be enormous, swamping Moffatt’s canoe and sweeping the 36-year-old backcountry veteran into the Dubawnt River. He never had a chance once he hit the frigid water.

“In one moment, this grand adventure had become a nightmare beyond all comprehension,” expedition member Fred “Skip” Pessl ’55 later wrote. “It happened so quickly, seemingly so easily; no violence, nothing dramatic; a brief struggle and then an empty finality.”

“In one moment, this grand adventure had become a nightmare beyond all comprehension.”

The tragedy has not simply faded into the sunset. Finding closure has been elusive. Murky memories and differing accounts have created a volatile mix of pain, finger-pointing, and Rashomon-like revisionism that continues to divide members of the crew. Some speculate that something darker was afoot than just an accidental drowning.

How did the seasoned Moffatt, whose prior experience included seven trips on the 610-mile Albany River in Ontario, some of them solo, make such a fatal miscalculation on the Dubawnt? Was is true that the crew engaged in mutinous talk? Did Moffatt’s apparent recklessness indicate he didn’t want to come home? “Years later I asked Skip, ‘Did my dad kind of commit suicide?’ ” says Creigh Moffatt, one of Art’s daughters. (Her Scottish name is pronounced “Cree.”) Her question echos claims made by others. “And Skip said, ‘What are you talking about? Let me sit you down and tell you a thing or two.’ ”

As a young boy, Moffatt had a thirst for extremes. He was raised on a Gatsby-esque estate on Long Island where his father, a Scottish immigrant, groomed horses for its wealthy owner. His mother died when he was 8. Moffatt attended Dartmouth only through the generosity of his dad’s boss. Before setting foot in Hanover, where he majored in geology, Moffatt took a train to the Albany River and set off with limited supplies in a canoe by himself, which spawned a lifelong passion for Native culture. Today his watercolor portraits of Cree tribe members who helped Moffatt along the trip peer from the walls of his former home, a Norwich, Vermont, farmhouse adorned with mementoes including a papoose-style cradle, a fur-lined jacket, and a polar bear skin.

“My dad would wear moccasins while walking down the street in the snow,” says Creigh, 70, who lives in the house and has kept it just as it was when Art shared it with his wife, Carol, Creigh, and another daughter, Deborah. “I think he was pretty different for his day,” Creigh says.

After graduation World War II recruiters tried to enlist Art, a skier, for the Army’s high-alpine 10th Mountain Division. He declined, citing his objections to armed conflict, according to Creigh. Instead, Moffatt signed up with the British army as an ambulance driver in Africa, an experience that hardened his anti-colonial mindset and made him even more comfortable in the bush.

After the war Moffatt headed west to write articles about skiing before returning to the Upper Valley, where in the 1950s he started an Outward Bound-type program for young adventurers. At the time the wilderness-travel industry did not really exist. By his early 30s, Moffatt was already a legend. One day Pessl, then in high school and considering Dartmouth, was skiing in Michigan when he met a man who knew Moffatt. The man strongly urged the teen to look up Moffatt if Pessl went to Dartmouth. Within days of arriving in Hanover, he did just that and was soon a regular customer. He accompanied Moffatt on two paddles down the Albany during school breaks. “Art took things to another level,” says Pessl, 88. “He was an inspiration.” Peter Franck, a Harvard student, was another early client.

For the fateful 1955 journey, which cost $600 to join, Moffatt cast a wider-than-usual recruiting net. Critics allege that he was asking for trouble by signing up inexperienced paddlers who had little familiarity with each other. He lectured about his travels on campus with an evocative slide show that helped convince Ed Lanouette ’57 and Bruce LeFavour ’57, who had been freshmen roommates, to join. Moffatt’s neighbor, a painter named Lewis Teague, recommended relative George Grinnell, who was despondent and aimless and holed up in a family house nearby. Harvard had expelled Grinnell for poor grades in 1953, and on the same day his father killed himself. “I never knew if my father knew that I had been expelled or if it was just a coincidence,” says Grinnell, 87.

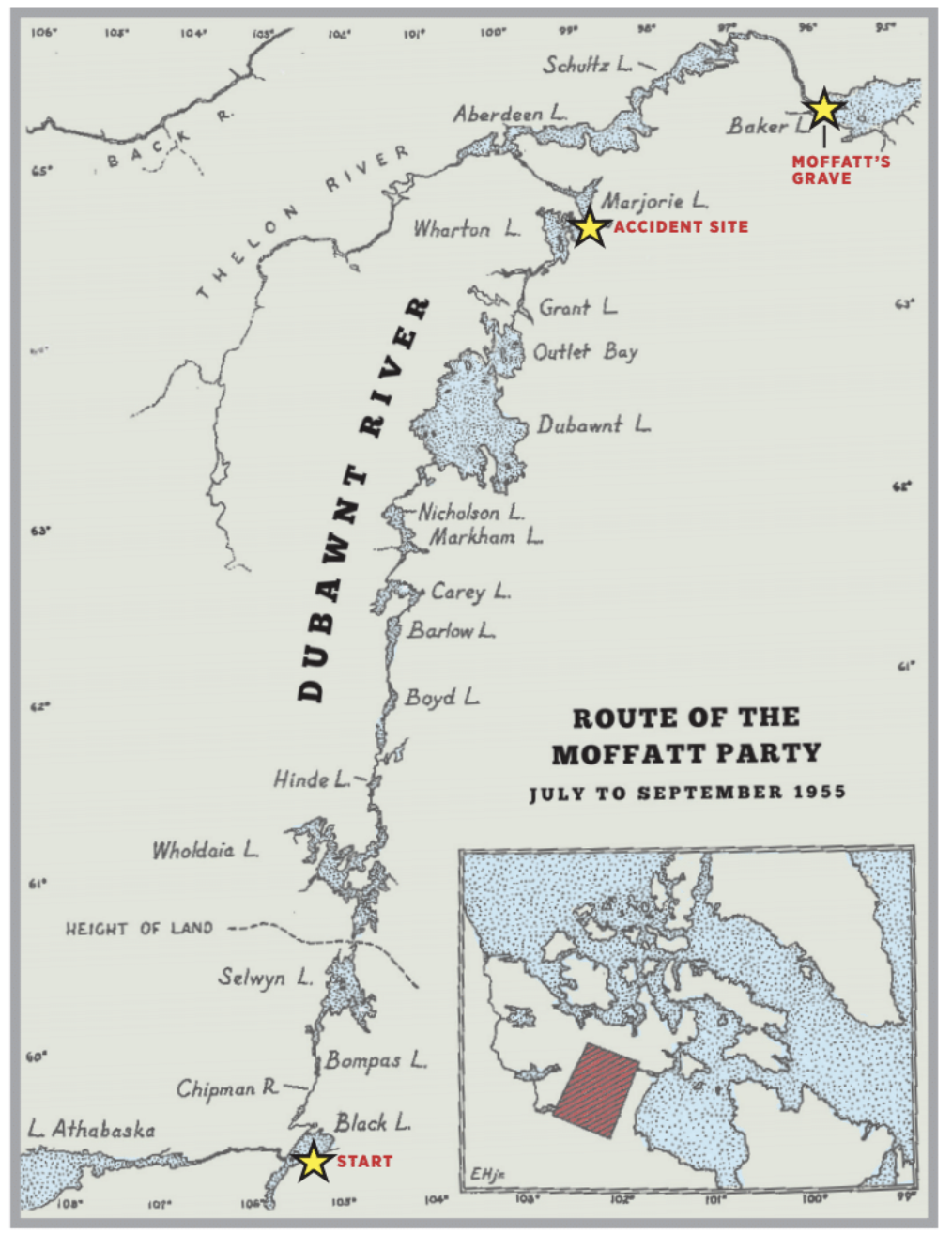

Lanouette, LeFavour, and Grinnell had never extensively canoed whitewater. The Dubawnt trip, a 955-mile wind from Black Lake, Saskatchewan, to Baker Lake, Nunavut, across the Barren Grounds region, included miles-long portages through unpopulated land in often harsh conditions. The route was not a regular destination, as the scarcity of maps and literature attested. Only two previous trips had been documented—the last by Canadian geologist J.B. Tyrell in 1893. Even Native people avoided the area because of its lack of firewood. After corresponding with Tyrell, then 96, Moffatt decided to retrace much of the previous journey along the choppy, zigzagging waterway strewn with boulders and a lack of wind-blocking trees.

In the hours leading up to July 2, when the group shoved off, the crew struggled to stow all the tents, sleeping bags, two rifles, macaroni, Spam, and biscuits. “It was hard to figure out how to put so much stuff in the canoes without sinking them,” Lanouette, 86, recalls. Another wrinkle was that Moffatt, with Pessl’s help, planned to film the trip and packed an 86-pound camera box. An accomplished photographer and early editor of Ski magazine in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Moffatt envisioned a new career as a wilderness filmmaker.

As the paddlers got under way, spruce-thick banks gave way to a sort of mossy moonscape interrupted by only the occasional empty cabin. The paddlers were impressed. “There is something fantastically beautiful in looking at that expanse of desolate, barren country,” according to an entry in Franck’s journal, one of several kept on the trip. Grinnell still speaks of a spiritual awakening on the tundra: “It changed my life.” Some days the voyagers took breaks to fish for grayling, hunt caribou, or forage for mushrooms. When rain or snow fell, they curled up in tents.

They also bickered—constantly—on shore and in the water. Grinnell groused about Pessl: “Skip’s good example, and the moralizing lectures that went with it, began to grate.” And Franck groused about Grinnell: “George lazed along all day, letting his paddle just float through the water most of the time and reading a book.” Moffatt took guff from all sides. Even Pessl, his right-hand man, lamented in his journal about Moffatt’s “rather annoying tendency to pass off personal preferences as group decisions.” According to Grinnell’s account, the frustration at Moffatt’s leadership almost boiled over into a revolt—which others strongly dispute.

Moffatt was not immune to annoyance. One day early in the trip he reprimanded his team for being too gung-ho about hunting because they need to conserve bullets, according to parts of his journal excerpted by Sports Illustrated in 1959. “The sharp talk at supper made everyone edgy,” Moffatt wrote. “Heretofore, we have all been equals. Now, I have assumed the sergeant’s position. But someone has to stop the foolishness before it has gone too far.”

By September 14 tensions ran high. An early-season blizzard had slammed their campsite a few days earlier, shredding a tent. Rations were dwindling. To save time they stopped scouting rapids from shore before plunging in. Had they done the extra legwork that day, they might have chosen a different route, a fact that almost nobody seems to contest.

As they plummeted into the churn that afternoon after lunch, two canoes flipped, throwing four men into the icy water. As Grinnell and Franck tried to save the men and their ration-filled backpacks, Grinnell fell in. He couldn’t pull himself back into the boat, so Franck dragged him ashore, according to Lanouette’s journal, which offers the most detailed account of the accident.

Franck and Grinnell then paddled back to pluck LeFavour and Pessl from the current and drop them on dry ground. Lanouette and Moffatt were next. The leader struggled to remain conscious as hypothermia set in. He held on to his canoe with one arm and clutched his heavy camera box with the other. After hauling him onto land, Franck built a fire, but all they had to keep Moffatt warm were soaking wet sleeping bags. He shook uncontrollably. When the shaking stopped, Moffatt was gone.

In the grim hours that followed, the survivors realized they had lost more than Moffatt. Most of their food and all of their guns had washed away. They had no radios to call for help. Convinced they would make it out only if they raced against the clock, the five survivors packed essential items into two canoes and charted a new course. They would hike 8 miles over hills to Aberdeen Lake, which would cut out 25 miles of paddling. Moffatt’s body, his cameras, and his film remained behind, tucked under the third canoe, which had been damaged by rocks.

Ten days and 100 miles later, the crew staggered into Baker Lake, where they met a Canadian Mounted Police officer, Clare Dent, who soon set out by plane to retrieve Moffatt’s body, now dusted with snow. With the blessing of his wife, Moffatt was buried in Baker Lake’s cemetery, where a simple white cross still marks his grave.

The survivors returned to their lives and classes—for better or worse.

“Before the trip I was filled with anxiety and sadness, and afterward, awe, gratitude, and love,” says Grinnell, who grew up in a New York City family of bankers. “Sometimes you just need a little bit of space.”

He graduated from Columbia in 1962, earned a Ph.D. from UC Berkeley, and became a professor at McMaster University in Canada. He also toiled away at a manuscript about the trip. His 14-draft, 40-year grind culminated with Death on the Barrens, a 1996 travelogue-autobiography.

Extreme travel also became a way of life. Grinnell completed dozens of other long-distance adventures with the barest of gear on foot, by bike, and by boat in the Alps, England, and the Arctic. In 1981, when one of his sons, Georgie, was struggling with drug addiction, Grinnell took him for an 800-mile row down the Saint Lawrence River in a 12-foot boat.“Georgie’s problems were very curable by a pilgrimage,” Grinnell says. But in 1984 Georgie, his girlfriend, a brother, and a cousin encountered a fierce storm during a weeks-long canoe trip down the Albany. All of them drowned after being capsized.

That such a disaster happened on a trip modeled on the one Grinnell had envisioned taking with Moffatt, in terrain that Grinnell viewed as a place of enlightenment, was a particularly cruel blow. “I did not know where I wanted to escape to,” Grinnell wrote in his book. “I just wanted to escape.”

Grinnell says he regarded Moffatt as his “surrogate father,” a kindred spirit with a similarly troubled soul. Depressed and possibly suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder from the war, Moffatt also appeared to be having trouble making ends meet, leading to behavior that could appear suicidal, Grinnell says. “Art’s resolve is getting weaker,” he wrote of the Dubawnt trip.“I had the sense he knew he would never make it home.”

At the very least Moffatt could be aloof, says Lanouette, his tent mate. “We didn’t have discussions long into the night. He was just the guy in the next sleeping bag,” says Lanouette, who did a stint in the Navy before working as a photo editor for National Geographic. He never got in a canoe again.

For Lanouette, who nearly died of hypothermia on September 14, Moffatt’s passing almost didn’t register. “I felt no emotion whatever—the body of a man, the body of a caribou, just another body—still, lifeless, not knowing or caring what went on about it,” Lanouette writes in his own journal, “just another victim in the never-ending process of life and death.”

Had Moffatt met his match with the Dubawnt? “I have never made such tough portages, had such sore feet, sore back, tired neck. Can’t recapture the confident, carefree air of the first Albany trip in 1937,” he wrote in his journal July 6, just a few days into the trip.

A few weeks later he realized he may have had a hernia and considered turning around, according to his journal.

Moffatt’s defenders often point to this same journal for proof of Moffatt’s will to live. In 2016 Allan Jacobs, a Canadian canoeing enthusiast and writer, began an aggressive, two-year effort to clear Moffatt’s name, including typing up Lanouette’s journal to provide fresh perspectives on the trip. “I conclude that a dead man was falsely accused [for his recklessness] for 55 years, in many instances knowingly,” wrote Jacobs, who declined to be interviewed for this story.

In several places in Moffatt’s journal, he does seem to embrace a future beyond the Dubawnt, including in an entry from just a few weeks before his death: “I smoke, drink tea, think of home, Carol, Creigh, and Debbo, of my study, and the children there with me when I get back, and the stories I’ll tell about my adventures in the north.”

And although it may not have been advisable to clutch an 86-pound camera box while trying to stay afloat, Moffatt did not just let his investment sink like a stone, defenders such as Jacobs add, suggesting a plan to return home. So furious was Pessl by the suggestion of a death wish that in 2013 he broke his longtime silence about the trip to pen his own book, Barren Grounds, which often reads as a point-by-point rebuttal of Grinnell’s take. They don’t even agree on the details of a grizzly’s visit on the banks of Grant Lake.

“There was a charge of severe irresponsibility, which is not true,” Pessl says. “Art Moffatt was a decent man.” In the nearly 70 years since Pessl and Grinnell said goodbye to one another in Nunavut, they have not spoken. Time has only deepened some wounds.

“I am still not ready to forgive [Grinnell],” Pessl says.

For Pessl, the trip’s big mistake was to fold in the movie project, which cost critical days when time was of the essence. Others argue the fatal flaw was a lack of deep connection among the crew, some of whom hadn’t met before. “Strapping young Dartmouth men? You only need so much of that on a trip like that,” says Carl Thum, 73, who in 1966 recreated a speedier and mishap-free version of the Moffatt expedition.

“Chemistry is extraordinarily important,” says Thum, now a Dartmouth writing instructor whose expedition group of four had been paddling together since they were teenagers.

Grinnell wasn’t the only one transformed. Pessl ditched plans for medical school to become a geologist, so as to spend as much time as possible in nature, a decision he made one blue-sky day on the trip. Employed by the U.S. Geological Survey, Pessl was able to do fieldwork in Iceland, Greenland, and Alaska while also becoming an ardent activist against the Vietnam War at home. “Moffatt’s view of the world, natural and international, opened my mind,” he writes.

LeFavour, who came from a newspaper family in upstate New York, seemed to be gripped by a bit of post-trip wanderlust himself. He dropped out of Dartmouth one credit shy of graduating and enlisted in the Army, which shipped him to France. Later he moved to the hippie enclave of Aspen, Colorado, and opened the Paragon, a French restaurant known for its farm-to-table ingredients; similar spots would follow in Idaho and California. He died in 2019, never addressing any of the Moffatt controversy publicly.

Franck graduated on time from Harvard and from Harvard Medical School before establishing a practice, with an infectious-disease focus, in Redding, California. But his love of remote corners never seemed to wane. Early in his career Franck traipsed through the jungles of Central America studying mosquito-borne viruses. And in the 1970s and 1980s he went back to the Barren Grounds for four more grueling, long-distance paddles, some of which got much closer to the Arctic Circle than his expedition with Moffatt.

In a 1992 letter to Pessl—the first time they had connected since Baker Lake—Franck, who died in 2013, recalled the Dubawnt as “one of the most important and precious experiences in my life,” adding that subsequent trips “never had the same feeling of remote other-worldliness as I remember from ’55.”

The transformative experience of the Moffatt expedition still can’t shake some loose ends. In the 1980s Dent, the Canadian officer, learned that Creigh Moffatt would be in Nova Scotia for her honeymoon and insisted on seeing her and her new husband while they were there. Over dinner at Dent’s house, Creigh recalls, the conversation turned to Art. “Dent said, ‘I want you to know I did a very thorough investigation, and I want you to know that nobody killed your father,’” says Creigh, who was 4 when her father died and says she could never really get her mother to talk about what happened. “I had never even thought about that.”

About 15 years later Dent wanted to talk again, this time taking it upon himself to show up outside the Upper Valley clinic where Creigh worked as a nurse. Eager to put a sad family chapter behind her, and agitated by their previous interaction, Creigh declined to meet him.

“Did that whole trip have some super-profound effect on him for some reason?” she says of Dent, who could not be reached for a comment. “Or did something change?” Creigh might never get a satisfying answer, though the questions may keep coming. Three or four people call her every year to inquire about Art and the circumstances behind his death 66 years ago. “Was it too dangerous a thing to be doing or was it just bad luck?” she asks. “It’s really hard to know.”

C.J. Hughes is a longtime contributor and a member of the DAM editorial board. Art Moffatt’s journal from the Dubawnt trip is available in Rauner Library.

Photographs by Skip Pessl, courtesy Creigh Moffatt