#1 Daniel Webster, class of 1801

#2 Theodor Geisel ’25

#3 Robert Frost, class of 1896

#4 Robert Smith, class of 1902

#5 Salmon P. Chase, class of 1826

#6 Thaddeus Stevens, class of 1814

#7 Nelson Rockefeller ’30

#8 Owen Chamberlain ’41

#9 George Perkins Marsh, class of 1820

#10 Samuel Katz ’48, DMS’50

#11 Edward Lorenz ’38

#12 C. Everett Koop ’37

#13 Louise Erdrich ’76

#14 George Bissell, class of 1845

#15 George Snell ’26

#16 Annette Gordon-Reed ’81

#17 Basil O’Connor, class of 1912

#18 Sylvanus Thayer, class of 1807

#19 Michael Arad ’91

#20 Albert Bickmore, class of 1860

#21 Fred Rogers ’50

#22 Grant Tinker ’47

#23 E.E. Just, class of 1907

#24 Rob Watson ’84

#25 James Nachtwey ’70

How We Chose the Top 25

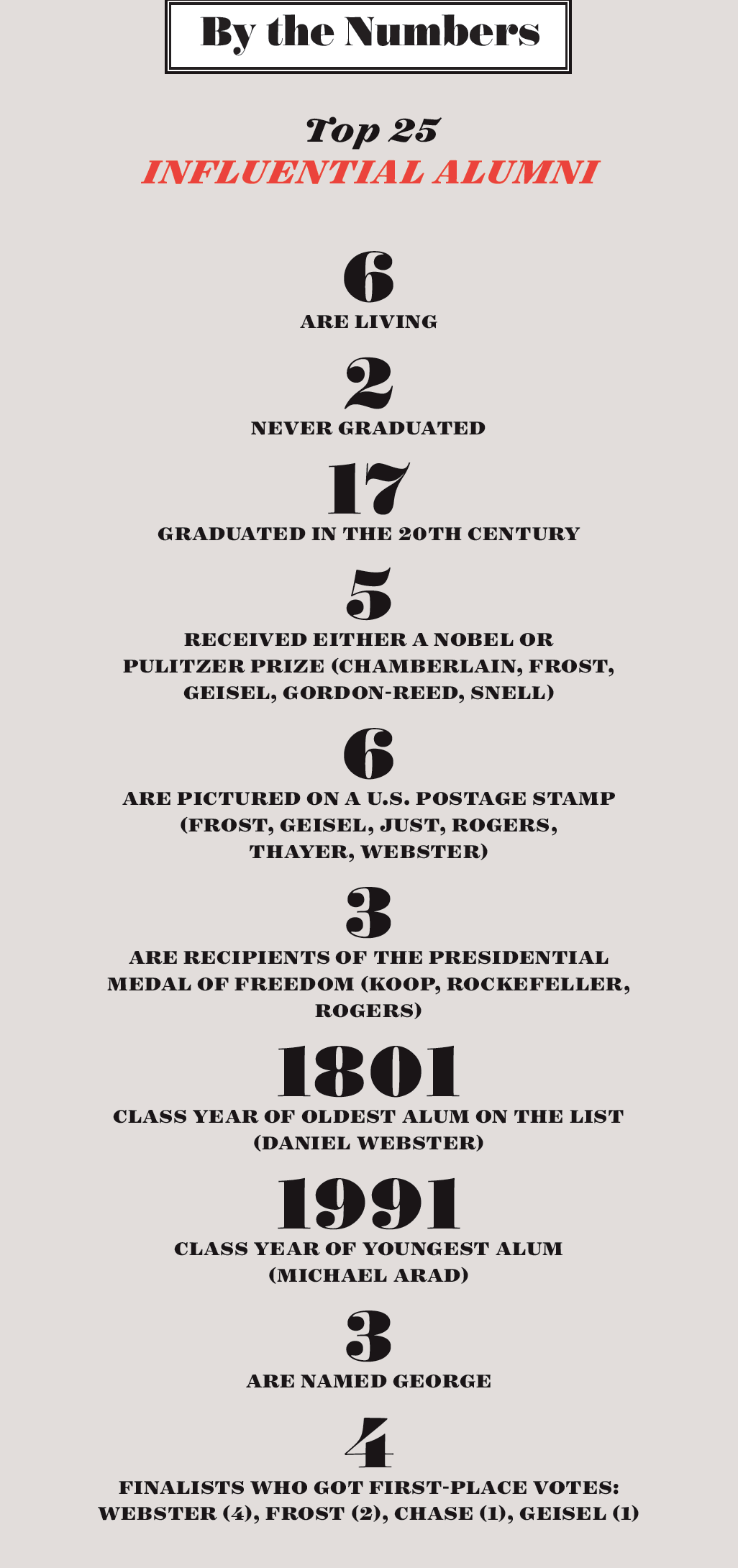

The Top 25: By the Numbers

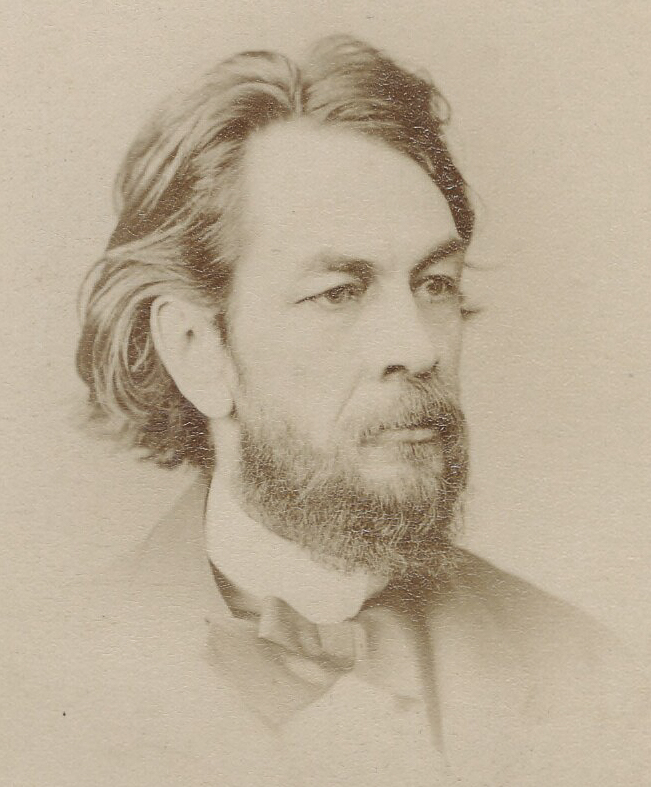

#1 Daniel Webster, class of 1801

Statesman and Orator

Even U.S. Chief Justice John Marshall had tears in his eyes that March day in 1818 as Daniel Webster reached the climax of his impassioned four-hour argument. Webster fixed his intense gaze on Marshall and uttered the words every Dartmouth graduate knows: “It is, as I have said, sir, a small college, but there are those who love it.” Trustees of Dartmouth v. Woodward was one of more than 200 cases Webster argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, many of them landmark rulings that shaped our interpretation of the Constitution. But the orator and statesman known as “the godlike Daniel” left a far greater imprint.

A swarthy complexion and jet-black hair earned this Salisbury, New Hampshire, native the nickname “Black Dan.” His titanic ego was evident early—he skipped his Dartmouth graduation because he wasn’t selected as the valedictory speaker. Soon after, he took up the law. Told that the field was too crowded, he allegedly replied: “There’s always room at the top.” That’s certainly where he wound up. “For over a century and maybe more,” current U.S. Chief Justice John Roberts tells DAM, “Daniel Webster represented for Americans what a lawyer was, both good and bad.”

Webster was a prolific Supreme Court advocate, often arguing more than 10 cases a year. The court frequently drew on Webster’s words in decisions that staked out broad powers for the federal government. Today a small bronze statue of him adorns the lawyers’ lounge at the high court. “The gaze on the statue is so stern it always had the effect of scaring me,” says Roberts, who frequently argued cases there before being appointed chief justice. “I suspect Webster had that effect on others in real life.”

Webster reached his greatest heights in the U.S. Senate, where he fought to preserve the union in the face of a growing North-South divide. Today New Hampshire Sen. Jeanne Shaheen sits at Webster’s Senate desk. “It’s humbling to have the desk of someone with such a profound legacy,” she says. “Webster’s great speeches in defense of our union delivered many timeless truths that are just as relevant today as when they echoed through the old Senate chamber.” Webster’s fierce eyes, deep voice, commanding presence, and carefully researched arguments produced a stunning impact. His powerful speeches in Congress and around the country cultivated a national spirit that had barely existed before.

In January 1830, he gave perhaps the most eloquent address in Senate history: his celebrated reply to South Carolina Sen. Robert Hayne, who had proclaimed that states should be able to ignore or “nullify” federal laws they disliked. Webster’s fiery dissent: Nullification would rip the country apart. “Liberty and union, one and inseparable, now and forever!” he thundered, earning him the accolade “Defender of the Constitution.” In far-off Illinois, newly minted lawyer Abraham Lincoln was among those he inspired.

Webster’s fierce eyes, deep voice, commanding presence, and carefully researched arguments produced a stunning impact.

Webster could be arrogant, profligate, and venal. He made many enemies—John Quincy Adams said he had a “rotten heart.” He hungered to be president, but when he ran in 1836 he came in the last of four candidates.

Webster was secretary of state for three presidents. He negotiated an important treaty with Great Britain and established a self-defense doctrine still used in international law. At age 68, back in the Senate, he made his last great speech on behalf of the Compromise of 1850, seeking to forestall a crisis between North and South. “I wish to speak today not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American,” he began. Secession was averted, but the respite was fleeting—war came a decade later. Webster’s stand cost him dearly. His supporters repudiated him as a traitor. The senator resigned but remained resolute. “I shall stand by the union…with absolute disregard of personal consequences.” As fitting an epitaph as any for one of the towering statesmen of the 19th century. —Rick Beyer ’78

#2 Theodor Geisel ’25

Author and Artist

He is the Shakespeare of children’s literature. No person has made more kids happier than Theodor Geisel (a.k.a. Dr. Seuss). At least 650 million copies of his 45 books have been published in 20 languages. For decades to come, children will nestle on parents’ laps and giggle at the zany doings of Sam I Am, Thing One and Thing Two, Cindy Lou Who, Mr. Gump (who owned a seven-hump Wump), and Aunt Annie’s alligator. He conjured words such as wocket, truffula, fiffer-feffer-feff, diffendoofer, thneeds, grickily gructus, and oodles more, including nerd.

Geisel visited Paris in the early 1920s, and Dali, Klee, and Miro influenced his art. His “divinely idiotic” tales, as one critic described them, took young readers to super-surreal Whoville, Solla Sollew, McElligot’s Pool, and Katroo, the place where the birthday birds live.

Twenty-seven publishers rejected his first book, And to Think I Saw It on Mulberry Street, in 1936. Some said it was too silly. Others objected to its rollicking anapestic tetrameter rhyme scheme, a meter its mischievous author knew would entrance young readers.

At the time, Geisel, 33, a successful commercial illustrator, was ready to give up as a writer. He was lugging his portfolio home when he saw his friend Marshall McClintock ’26 on Madison Avenue in New York City. By chance McClintock had just been hired as a children’s book editor, and by day’s end Geisel had a book deal.

Fame came slowly before his literary star went supernova with the 1957 publication of The Cat in the Hat. He wrote it after being challenged by an editor to create a fun book for first-graders, one brimming with maximum merriment that would encourage a love of reading—and use as few simple words as possible.

A perfectionist, Geisel chose a bold red and a brilliant blue for its illustrations, hues he knew would appeal to children. His mad-hatted cat has sold more than 7 million copies, making it the ninth bestselling children’s book of all time, according to Publisher’s Weekly, which lists it as one of 15 Seuss titles in its top 100 list.

The sly Seuss (his middle name, which he first used in The Jack-O-Lantern and thought should be pronounced soice) told timeless tales. Their themes of love, courage, and decency are universal. Horton learns to respect individuals, no matter how small. Sneetches warn of anti-Semitism, or perhaps merely the woes of snobbery. The greedy Grinch repents his worship of consumerism. The Lorax protects nature.

No person has made more kids happier than Theodor Geisel.

Love of liberty pulses through everything Geisel wrote. (He knew war firsthand. Assigned to a documentary-filmmaking unit, he was trapped for three days behind enemy lines during the Battle of the Bulge.)

When Dartmouth gave him an honorary degree in 1955, the citation hailed his creative daring: “You single-handedly have stood as St. George between a generation of exhausted parents and the demon dragon of unexhausted children on a rainy day.”

Geisel courted controversy in 1984 with The Butter Battle Book, which suggested that no nation in a nuclear arms race could claim moral superiority.

He also wrote 13 books under the semi-anagramic name of Theo LeSieg, as well as two for adults, including You’re Only Old Once! (A Book for Obsolete Children), which appeared in 1990, one year before his death at the age of 87.

His influence on young people remains strong at Dartmouth. Freshmen dine on green eggs and ham at Moosilauke Ravine Lodge. The 2012 renaming of the Audrey and Theodor Geisel School of Medicine recognized his substantial gifts to the College.

Geisel’s children are everywhere. He had none of his own. “You have them,” he once said. “I’ll entertain them.” —George M. Spencer

#3 Robert Frost, class of 1896

Poet

Robert Frost’s place in American culture is easy to measure and impossible to overstate. From his first book (A Boy’s Will, 1915) to his recitation of “The Gift Outright” at President Kennedy’s 1961 inauguration, Frost dominated the literary landscape. He won four Pulitzers for poetry. He was nominated more than 30 times for the Nobel Prize in literature, and he received a Congressional Gold Medal.

Frost took 19th-century tools of meter and rhyme and made them new. He radically reinvented the narrative poem, combining technical brilliance with ordinary speech—the colloquialisms of New England hill farmers. Unlike pastoral poets who preceded him, Frost brought a dirt-under-the-fingernails understanding of husbandry and botany to his poetry. He was a farmer. He lived through hard times and personal tragedy. His poetry transcended sentiment because it was real, and its realities were hard-earned. Like the poet himself, his poetry endured.

Frost’s poems examined the facts of the world. “A brook, a new calf, neighbors at work, the death of a child, a solitary walk; without preaching, the poet treats each subject with a loving care until the heart of the matter rises up, seemingly from our own eyes,” wrote fellow New England poet Steven Ratiner in 1981. “Using broad descriptive strokes and a perfectly balanced tension between what is told and what is held back for the reader to imagine, Frost’s images lift up off the page. Though they are simple in nature, the wonder of his lyrics is that they conjure strong and vibrant histories that we somehow have shared all along.”

Uncle Sam printed a special edition of Frost’s poems for troops fighting in World War II. Frost went to the Soviet Union as a cultural ambassador and met Premier Nikita Khrushchev. A performance artist before the term was invented, this white-haired, rumpled man with a New England accent came into everyone’s homes on radio and TV and became the face and voice of American letters. “He was not only a poet but a public institution,” wrote author Danny Heitman in 2014. “His presence is as familiar to his fellow Americans as the Grand Canyon or the Washington Monument.” Indeed, at the dedication of Amherst’s Robert Frost Library, Kennedy called Frost one of “the granite figures of our time” whose art was one of “the deeper sources of American strength.”

Frost lived through hard times. His poetry transcended sentiment because its realities were hard-earned.

Frost always insisted his goal was “just to lodge a few poems where they’ll be hard to get rid of.” His austere meditations live in our collective psyche. “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” “Mending Wall,” “The Road Not Taken,” “Birches,” “After Apple-Picking,” “Fire and Ice,” “Design,” and “Nothing Gold Can Stay” explore themes of duty, isolation, free will, youthful spirit, mercy, the brevity of life, and the inevitability of death.

For all the accolades and influence Frost had, his greatest impact is on the thousands of ordinary individuals who read poetry because of the introduction he gave them and who have richer lives as a result.

“Dartmouth is my chief college,” Frost liked to say, “the first one I ran away from. I ran from Harvard later, but Dartmouth first.” For generations of American readers, Frost remains the chief poet, the first one they read and did not run away from. —Jim Collins ’84

#4 Robert Smith, class of 1902

Alcoholics Anonymous Cofounder

Heavy drinking punctuated Robert Smith’s college days. “After high school came four years in one of the best colleges in the country, where drinking seemed to be a major extra-curricular activity,” he wrote later in life.

Smith became a surgeon and kept drinking—heavily. “I used pills and booze every day,” Smith said. “I woke up in the morning with the jitters, took a sedative to steady my hands for surgery.... Sometimes, in the operating room, I’d be high as a kite. Lucky I haven’t killed somebody.”

In 1935, in Akron, Ohio, he met fellow alcoholic Bill Wilson, a New York City stockbroker. Wilson, who had recently stopped drinking, spent 30 days helping Smith do the same. That year they created Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), which changed how the world views alcoholism, once regarded as a moral weakness and now considered a disease. Smith and Wilson’s 12-step program is still used today. Wilson tends to get most of the credit for founding AA, but Smith is equally deserving. Known to AA members as “Dr. Bob,” he was, according to those who knew him, a humble man who never sought the limelight.

AA is grounded in a belief in a “higher power” and that having a spiritual awakening can lead to a life of sobriety. In addition, the program stresses the importance of finding a fellow alcoholic (or sponsor) and attending meetings to find support from other alcoholics.

“Working together, the two founders created a program that was based on religious and psychological truths, as well as their own practical experience, and turned it into a simple 12-step program that has helped tens of millions around the world,” Dr. Irving A. Cohen, a distinguished fellow of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, tells DAM.

Dubbed the “Prince of Twelfth Steppers,” Smith personally helped more than 5,000 alcoholics pro bono. When he died in 1950, he had been sober for 15 years. —Lambeth Hochwald

#5 Salmon P. Chase, class of 1826

Politician and Judge

Salmon P. Chase ticked off the offices on his rapid rise up the political ladder: governor of Ohio, senator, secretary of the U.S. Treasury, chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. He helped found the Republican Party and was a leader in the fight to abolish slavery. Missing from his impressive resume is the job he most desired and was convinced he richly deserved: president of the United States.

Chase was 6 feet tall and looked every inch the statesman. He neither drank nor smoked. If he had a sense of humor, it escaped anyone’s notice. “He seldom told a story without spoiling it,” quipped The Atlantic Monthly. Deeply religious, he combined moral rectitude with nakedly opportunistic ambition. His self-regard was a byword among his peers. “He thinks there is a fourth person in the (holy) trinity,” cracked Ohio Sen. Benjamin Wade.

Chase’s life was marked by tragedy. He married three women, each of whom died young. He relied heavily on his daughter, Kate, who presided at social functions and acted as his chief advisor.

After he lost the Republican nomination in 1860, Chase grudgingly joined Lincoln’s cabinet as secretary of the treasury. To finance the Union’s war efforts, he set up a national banking system and issued the government’s first-ever paper currency, known as greenbacks. (He also added the phrase, “In God We Trust,” to coins.) Former Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson ’68 admires Chase’s creativity in bankrolling the war, but not the decision to put his own portrait on the $1 bill. “I don’t want to criticize a fellow Dartmouth graduate, but I think Washington was a better choice,” he tells DAM.

Chase frequently sought to promote his political ambitions, often at Lincoln’s expense. “He didn’t serve the president as well as he might have,” says Paulson. Eventually Lincoln wearied of Chase’s antics and accepted his resignation. Nevertheless, Lincoln nominated Chase to be chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court a few months later. “That demonstrates Lincoln’s greatness,” says Paulson, pointing to the president’s ability to look past personal differences and recognize Chase’s abilities.

Chase set up a national banking system and issued the government’s first-ever paper currency.

Even serving as chief justice failed to slake Chase’s ambition. He changed parties to seek the Democratic presidential nomination in 1868. Four years later he changed parties again for another failed attempt at the top job. He died of a stroke in 1873.

Ultimately, Chase may simply have been a victim of bad timing. “Chase was a great man,” said Chief Justice William Howard Taft 50 years after Chase’s death. “He has had the disadvantage in history of comparison to Lincoln.” —Rick Beyer ’78

#6 Thaddeus Stevens, class of 1814

Congressman and Abolitionist

“No man assailed him without danger or conquered him without scars,” declared one contemporary of Thaddeus Stevens. The congressman was a warrior. He agitated ceaselessly against slavery and for the rights of blacks. He was instrumental in the passage of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery in 1865. He took on a president who opposed him and nearly removed him from office. Full of vitriol, both hater and hated, Stevens gave no quarter.

His Dartmouth roommate recalled that Stevens was “inordinately ambitious, bitterly envious of all who outranked him as scholars, and utterly unprincipled.” Stevens was selected as the 1814 Commencement speaker but was enraged when he was not elected to Phi Beta Kappa.

Stevens practiced law in Pennsylvania, where he became a committed abolitionist and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. During the Civil War he was a leader of the Radical Republicans, who favored immediate abolition and harsh measures against the South. “Free every slave—slay every traitor—burn every rebel mansion,” he thundered. Southerners returned his hatred. One newspaper editor labeled him “this wicked man…this demon.” Even Northern editors referred to him as an “evil genius.”

Stevens was an imposing 6 feet tall and had a perpetual grimace. He tried to hide his bald head with a preposterous brown wig that fooled no one. He loved to gamble and had a slashing wit. Interrupted on the House floor, Stevens shot back: “I yield to the gentleman for a few feeble remarks.” For 20 years he lived with his mixed-race housekeeper, Lydia Smith. It was widely believed they were living as man and wife, though Stevens denied it.

Stevens strove “to ameliorate the condition of the poor, the lowly, the downtrodden of every race.”

Stevens didn’t just want the slaves freed, he wanted them to have the vote, education, and land of their own. When President Andrew Johnson failed to act swiftly to give blacks their rights, Stevens convinced the House of Representatives in 1868 to impeach Johnson. Then 73 and gravely ill, Stevens was carried to the Senate in a chair to deliver the news. Three months later, the president evaded conviction in the Senate by one vote, and Stevens died shortly thereafter.

“My lifelong regret is that I have lived so long and so uselessly,” the dying congressman told a reporter. A more fitting tribute lies in the words he spoke after passage of the 13th Amendment: “I will be satisfied if my epitaph shall be written thus, ‘Here lies one who never rose to any eminence, and who only courted the low ambition to have it said that he had striven to ameliorate the condition of the poor, the lowly, the downtrodden of every race and language and color.’ ” —Rick Beyer ’78

#7 Nelson Rockefeller ’30

Politician and Philanthropist

In November 1927 the White and Connecticut rivers overflowed their banks, burying White River Junction, Vermont, in mud. Among the hundreds of Dartmouth students who rushed to help was Nelson Rockefeller. Requesting to be sent to work at a remote stretch of riverfront, away from prying reporters and photographers, he explained, “If we get our picture in the paper, Father cuts our allowances.”

His obscurity would be short-lived. While in his 20s, Rockefeller aided his redoubtable mother, Abby, in establishing New York City’s groundbreaking Museum of Modern Art. At the same time, he backstopped his father in building nearby Rockefeller Center. In his 30s Rockefeller waged economic and social warfare against South American Nazis at the behest of Franklin D. Roosevelt, his lifelong political hero and the first of three presidents he would serve as an appointee.

Art, commerce, politics—as the most dynamic of John D. Rockefeller’s grandchildren, Rockefeller might be forgiven for believing that he could have—and do—it all. Including the presidency. Like Theodore Roosevelt, in whose lap he once sat as a child, Rocky believed Americans must justify their wealth by promoting capitalism with a conscience.

Toward that end, after WW II he created Latin American companies whose profits went to build schools and combat disease in the region. At the organizing conference of the United Nations in 1945, Rockefeller engineered a clause in its charter that permitted free nations to form defensive coalitions—the forerunners of NATO.

For 15 years, beginning in 1959, he was New York’s innovating, if costly, governor. Insisting that state’s rights must yield to a state’s responsibilities, Rockefeller spent more in the mid-1960s to combat pollution, support higher education, and promote the arts than Uncle Sam did in the other 49 states combined. The original Rockefeller Republican, he opposed the death penalty and supported abortion rights.

Possibility was in his DNA. “There is no problem that cannot be solved,” Rockefeller maintained. This staunch refusal to acknowledge limits produced Albany’s Empire State Plaza and Manhattan’s Battery Park City, and it fashioned the State University of New York into the world’s largest institution of higher learning.

A disappointing term as Gerald Ford’s vice president, and three unsuccessful presidential campaigns of his own, fed a sense of failure. He had much in common with one of Dartmouth’s other would-be presidents—Daniel Webster. Both were men whose principles got in the way of their ambitions, but that didn’t stifle their influence. “What a man does for others, not what they do for him, gives him immortality,” said Webster. —Richard Norton Smith

#8 Owen Chamberlain ’41

Physicist

Owen Chamberlain made a scientific breakthrough of cosmic proportions. He proved the existence of the antiproton, or antimatter. His achievement, which earned him (and his University of California, Berkeley mentor Emilio Segré) the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physics, became a cornerstone of the Standard Model, the physics theory that explains what the universe is and what holds it together.

“The discovery of antiprotons,” says Nobel physicist William Phillips, “illustrates one of the most remarkable, appealing aspects of scientific research” because it built upon earlier discoveries and confirms that all particles have perfect twins differing only in their electric charge.

The continuous nature of scientific discovery fueled three intertwined loves of Chamberlain’s life: learning, physics, and teaching. In high school he was fascinated by solving physics puzzles, unraveling their mysteries for fun and zipping through complex science and math homework in minutes.

At Dartmouth he was drawn to physics because “it was always the easiest thing to do,” he recalled. He won the prestigious Thayer Prize in Mathematics and the Kramer Fellowship, which funded his initial graduate studies at Berkeley, where he taught from 1948 to 1989. During World War II he was one of the physicists who developed the atomic bomb as part of the Manhattan Project.

Professor Chamberlain was beloved for being an approachable mentor. “His informality came as a major cultural shock to me. I had been brought up to think of professors as remote deities whose first names were known only by their mothers,” says former Chamberlain student, colleague, and biographer Herbert Steiner. “He was who we would go to when we did not understand something. As one of our graduate students once put it: ‘He is one smart dude.’ ”

Chamberlain died in 2006 at the age of 85. He spent the latter half of his life advocating for world peace, free speech, and human rights. He directed the Ploughshares Fund, a foundation dedicated to creating a nuclear weapon-free world.

Although his discovery was momentous, Chamberlain emphasized he was merely one person in the history of curious physicists. “Each generation of scientists,” he said in his Nobel acceptance speech, “stands upon the shoulders of those who have gone before.” —Maryellen Duckett

#9 George Perkins Marsh, class of 1820

Environmentalist

George Perkins Marsh’s 1864 book, Man and Nature, a pioneering work of ecology and advocacy, earned him the title “The Prophet of Conservation.” Marsh drew on a lifetime of observing deforestation in Vermont. He documented alpine erosion in the Italian alps, the devastating effects of overgrazing and logging in the once-great forests of the Roman Empire, the negative effects on water quality and changed weather patterns, and the cascading side effects of industry.

“Man is everywhere a disturbing agent,” he wrote. “Wherever he plants his foot, the harmonies of nature are turned to discords.” Written two years before the term “ecology” was coined, his book came at a time when people accepted the notion of an abundant nature whose bounty was boundless. Marsh argued that humans were fouling their own nest at a rate that would be catastrophic unless reversed. He sparked the Arbor Day movement, inspired the creation of New York’s Adirondack Park, laid the foundation for the U.S. national forest system, and—alongside writings by contemporaries John Muir and Henry David Thoreau—gave birth to the nation’s environmental consciousness. A century later, U.S. Interior Secretary Stewart Udall wrote that Man and Nature was “the beginning of land wisdom in this country.”

A Renaissance man, Marsh had other mind-boggling accomplishments. In the mid-19th century he was the nation’s foremost Scandinavian scholar and expert on railroads, Renaissance art, and camels. A gifted linguist proficient in 20 languages (seven of which he picked up at Dartmouth), Marsh wrote the monumental book, The Origin and History of the English Language (and a text on Icelandic grammar).

Born in Woodstock, Vermont, in 1801, Marsh was a lawyer, sheep farmer, newspaper editor, and owner of a woolen mill and marble quarry. While representing Vermont in Congress in the 1840s, his eloquent speech in the U.S. House of Representatives laid out a persuasive framework for the creation of the Smithsonian Institution, unlocking funds frozen more than a decade by squabbling politicians.

Marsh gave birth to the nation’s environmental consciousness.

He later became ambassador to Turkey and then Italy, becoming the second-longest-serving U.S. diplomat after Benjamin Franklin. While living abroad he presented the plan, based on his detailed measurements of Egyptian obelisks, that reshaped the construction of the Washington Monument. —Jim Collins ’84

#10 Samuel Katz ’48, DMS’50

Pediatrician and Virologist

He may not wear a cape, but Dr. Samuel Katz is a superhero to the millions of kids he has saved. His superpower: researching, developing, and championing vaccines. Katz helped pioneer and promote widespread use of the measles vaccine, which wiped out the disease in the United States and transformed global children’s health. While his measles work is legendary, it is only an early chapter in a 60-plus-year-and-counting medical career devoted to bringing the biggest infectious disease breakthroughs to the planet’s smallest patients—children.

“The impact Sam Katz has had on medicine and humanity is staggering,” says Dr. William Steinbach, chief of the pediatric infectious diseases division at Duke University, where Katz is the chairman emeritus of pediatrics. “Aside from the countless people he directly influenced as a trusted mentor, invaluable colleague, physician, and friend, his measles vaccine has saved an estimated 118 million lives worldwide, about one-third of the current U.S. population.”

Katz didn’t set out to be a disease fighter. Music was his passion growing up. When World War II depleted the pool of local percussionists, Katz landed dance hall drumming gigs. A penchant for marching to his own beat led him to leave Dartmouth to enlist in the Navy in 1944. Upon being posted to a hospital training school, he discovered his true calling—medicine.

After the war Katz earned his undergraduate degree in 1948, graduated from the then two-year Dartmouth Medical School program, completed his pediatric residency, and worked at Boston Children’s Hospital with Nobel laureate John Enders for 12 years developing the measles vaccine.

Before it was licensed for human use in 1963 (after it was proven safe and effective in monkeys), Katz demonstrated his confidence in his work by inoculating himself and his four children. That same year Katz traveled to Nigeria to help implement its vaccination program, a mission that transformed him from a self-described “parochial, naive young man” into a passionate global health advocate.

“When we went to Nigeria I learned mothers would say, ‘You don’t count your children until measles has passed,’ because they knew how many children died,” said Katz. He later applied his measles vaccine experience to fighting pediatric AIDS. Katz and his pediatric infectious disease specialist wife, Dr. Catherine Wilfert, were the first in the United States to treat children with AZT, the first FDA-approved AIDS medication.

Katz also has been involved in studies of vaccinia, polio, rubella, influenza, pertussis, dengue, and HIV, among others. But it is his work outside of the lab—teaming up with the World Health Organization to push for worldwide measles vaccinations—that has earned him the title “Vaccine Ambassador”—an apt identity for a real-life superhero. —Maryellen Duckett

#11 Edward Lorenz ’38

Mathematician

In 1972 Edward Lorenz asked, “Does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?” The phrase has become one of the most vivid images in science, an elegant warning that the order we take for granted is an illusion. Lorenz’s research founded the new discipline of chaos theory, which overthrew the accepted view that the universe functions according to a clockwork plan.

“Perhaps the butterfly, with its seeming frailty and lack of power, is a natural choice for a symbol of the small that can produce the great,” Lorenz wrote years later.

As with many great discoveries, chaos theory was discovered by chance. In 1959 at MIT, Lorenz found that if initial conditions in his weather forecasting models were altered even slightly, the output would stray wildly. At first he thought his computer was to blame. But there was no error, only a sensitivity that made complex systems unpredictable, or, as Lorenz put it, chaotic.

As a child in Connecticut, Lorenz had been enthralled by New England’s famously changeable weather. He came to Dartmouth in 1934 intending to study math. While he was in Hanover, pinball became popular. As Lorenz recalled in his biography, “Town authorities decided the machines violated the gambling laws” because the game presumably relied on luck, not skill. Lorenz was perplexed: Pinball did involve skill. But why could no one exhibit it with any consistency?

“The reason was chaos,” he wrote.

His theory is best known for its influence on climatology, but it has also informed a host of other scientific disciplines. Cancer experts now know that tumor growth can be drastically altered by a single mutation. Urban planners use chaos theory to study traffic patterns, which can by utterly unpredictable.

He made a discovery about the world at large, not some detail within it. He saw that the mechanistic understanding of the natural world in place since the Enlightenment was woefully simplistic. When Lorenz received the Kyoto Prize (Japan’s equivalent of the Nobel) in 1991, he was hailed for making “one of the most dramatic changes in mankind’s view of nature since Sir Isaac Newton.”

Lorenz died in 2008 at the age of 90. Since 2011, MIT has hosted the Lorenz Center, which studies climate. “Lorenz was from the old school,” says one of its chairs, Kerry Emanuel. “He was a man driven by his curiosity, not by fame or wealth.” —Alex Nazaryan ’02

#12 C. Everett Koop ’37

U.S. Surgeon General

C. Everett Koop changed the way American medicine was practiced—and that was before he became the nation’s top doctor. He began his career as a pediatric surgeon at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in 1946, at a time when pediatric surgery wasn’t a medical specialty. Through the next 35 years he developed safer anesthesia for infants and toddlers and performed surgeries once dismissed as impossible, successfully operating on newborns with spina bifida and cleft palate and pioneering a new method of repairing hernias. He established the nation’s first neonatal surgical intensive care unit. He separated dozens of conjoined twins. He proved that conditions once thought hopeless were correctable. He saved the lives of thousands.

Koop is most widely remembered as America’s most influential surgeon general. Part of his prominence came from his presence. He stood more than 6 feet tall, had a stentorian voice and a bushy, biblical-looking chinstrap beard that reflected his stern religious beliefs, and wore a white dress U.S. public health service uniform with gold-braid and epaulettes.

Putting science and public health above ideology, Koop from 1982 to 1989 challenged the Reagan administration’s positions on controversial issues. He refused to issue a report that said abortions were harmful to women because data didn’t support those findings. He authored withering reports that revealed smoking was an even greater health hazard than previously believed. He condemned the tobacco industry’s deceptive advertising and publicized the deadly consequences of second-hand smoke. He laid the groundwork for laws that banned smoking in many public places. During his watch, the percentage of Americans who smoked fell by nearly 25 percent.

His greatest achievement may have been educating Americans about AIDS, a then little-understood and much-dreaded disease that some feared would turn into the century’s greatest public health catastrophe. Koop spoke out about intravenous drug use, gay sex, and condom use. “I’m the nation’s doctor, not the nation’s chaplain,” he said, adding that he made policy decisions “dictated by scientific integrity and Christian compassion.”

To dispel myths and fight fear, his office sent the plainspoken brochure, Understanding AIDS, to all 107 million U.S. households, the largest mass-mailing in American history. He singlehandedly shifted the debate from morality to medical care and compassion. He remained a vocal advocate for medical research and education—and a model of public service—until his death in 2013 at the age of 96. —Jim Collins ’84

#13 Louise Erdrich ’76

Author

Growing up in Wahpeton, North Dakota, Louise Erdrich collected her first royalties in the form of pocket change. Her father shelled out five cents for each of her childhood manuscripts—stories of lonely girls with hidden talents. Forty years later, after she had won most of America’s top literary honors, he gave her a roll of antique nickels. He owed her.

A biracial citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, Erdrich draws on Anishinaabe oral tradition and Germanic lore in her 30 published books—poetry, memoirs, short fiction, and the 16 epically interwoven novels for which she is most celebrated.

“She is, like Faulkner, one of the great American regionalists, bearing the dark knowledge of her place,” Philip Roth once said, referencing the fictional North Dakota reservation where much of her work is set. “She is by now among the very best American writers.”

Erdrich arrived auspiciously at Dartmouth in red cowboy boots as a member of its first coed class and first modern indigenous cohort, and she graduated in a pair of refurbished moccasins. She worked odd jobs—waiting tables, editing a newspaper, teaching poetry to inmates—while establishing herself as a poet, then as a short story writer, and, finally, in 1984 as a bestselling author with her debut novel Love Medicine, whose “beauty…keeps us from being devastated by its power,” raved Toni Morrison.

Erdrich’s stories blend the hyper-realistic with the mystical and the apocalyptic with the mundane to remind readers how bizarre reality can be. In her universe, a violin lost for decades washes ashore in an abandoned canoe. A woman enters into a marriage pact with a lake spirit. Her recurring characters—Indian boarding school survivors, German immigrants, and veterans-turned-priests—draw on shared memories and ancestral geography, and each new chapter in her saga feels bracingly original and brutally sincere.

“She is, like Faulkner, one of the great American regionalists, bearing the dark knowledge of her place.”

Today Erdrich runs an independent bookstore in Minneapolis. She still composes her first drafts by hand. She is not slowing down. Her latest novel, Future Home of the Living God, published to acclaim, took a dystopian turn, inspiring some to compare her to Kurt Vonnegut. She brushes off comparisons. After all, there will never be another Faulkner or Vonnegut. There won’t be another Erdrich either. —Savannah Maher ’17

#14 George Bissell, class of 1845

Industrialist

While visiting his mother in his hometown of Hanover in 1853, George Bissell paid a social call on Dr. Dixi Crosby, the College’s professor of surgery and obstetrics. Bissell noticed a jar labeled “rock oil” on his shelf. Crosby said another alum had brought it from western Pennsylvania and claimed it had intriguing properties as a lubricant and illuminant.

Bissell took note. As it happened, his life was in a muddle. Yellow fever epidemics had chased him out of New Orleans, where he’d been an educator and newspaperman. He planned to study law, but now the little jar held his attention.

Almost from that moment, Bissell saw two things plain. The oil, properly refined, could replace scarce, expensive whale oil as the predominant fuel for artificial light. And there was no reason why it couldn’t be extracted from deep underground, as water was. He also sensed that oil’s moment was about to arrive—and that he needed to act immediately.

Within 18 months he created America’s first oil company, Pennsylvania Rock Oil. He purchased 105 acres for $5,000 along Oil Creek near Titusville, Pennsylvania. The next few years were difficult. Investors grew impatient and caused repeated crises. Bissell’s unusual methods were mocked. The drilling kept coming up dry. The enterprise seemed to founder. Then on August 27, 1859, at a depth of 69 feet, his rig struck oil. While others celebrated, Bissell quickly bought as much nearby land as he could.

Before long he became the world’s first oil baron. He wisely built a barrel-making factory, and soon had additional interests in railroads, banks, hotels, and insurance. He was widely praised for his acumen, intelligence, and honesty.

“It was Bissell’s early vision that put the American oil industry on its feet.”

“Among the great oil pioneers, Bissell was a giant,” wrote oil historian Neil McElwee in 2007. “It was Bissell’s early vision, initiative, unwavering commitment, personal sacrifice, proven integrity, and 15 years of entrepreneurial risk that put the American oil industry on its feet.”

Bissell remained a great friend of Dartmouth. When he gave the College funds in 1867 to build a new gym, he insisted it include six bowling alleys “in remembrance of disciplinary troubles in which he’d fallen because of his indulgence in this sinful sport.” —Charles Monagan ’72

#15 George Snell ’26

Geneticist

George Snell was a lifesaver, thanks to the organ and tissue transplants made possible by his pioneering genetics research. He earned a 1980 Nobel Prize for decades of work in immunology. He identified genetic factors (the major histocompatibility complex, or MHC) in mice required for successful transplantation. MHC regulates immune responses, and since mice are biologically similar to people, Snell’s discovery paved the way for human transplant surgery.

“George is one of the giants of biomedical research,” says Dave Serreze, a professor at the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, where Snell conducted groundbreaking genetics research and, late in his career, served as one of Serreze’s mentors. In addition to enabling transplantation, Snell’s immunology discovery improved the effectiveness of vaccines and may have important future implications for the prevention of autoimmune diseases, such as Type I diabetes and arthritis. Snell also generated the first strains of mice that became staples of modern genetics study. Much of today’s immunological research is possible because of Snell’s innovative work, according to Serreze.

A Massachusetts native, Snell had old-fashioned Yankee ingenuity and a keen scientific intellect. He credited his father’s relatives (three of whom held patents) for instilling his penchant for invention, and his mother, an avid gardener whom he called a “natural planner,” for his attention to detail and organizational skills. Summer vacations spent working on his family’s South Woodstock, Vermont, farm nurtured Snell’s lifelong interest in gardening, farming, and forestry.

It was Snell’s experience as a biology major, however, that most shaped his future. “A genetics course taught by professor John Gerould proved particularly fascinating,” he wrote in his autobiography. “It was that course that led me to the choice of a career.” On Gerould’s recommendation, Snell earned his Ph.D. in genetics at Harvard under Dr. William Castle, one of the world’s most influential geneticists.

Snell died in 1996 at the age of 92. While his impressive achievements include a Nobel Prize and a legacy as the father of an entire scientific discipline, immunogenetics, one of Snell’s most coveted honors eluded him. “George was such an avid gardener that when he won his Nobel he actually was a bit disappointed,” Serreze recalls. When the call came, “He was hoping he had finally won a state fair prize for his vegetables. I remember his secretary telling him, ‘No, George, you won the Nobel Prize.’ ” —Maryellen Duckett

#16 Annette Gordon-Reed ’81

Historian

It was one of the biggest controversies in American history: Did Thomas Jefferson father the seven children of his slave, Sally Hemings? For two centuries the debate raged. Was it true? Impossible? Almost every Jefferson biographer dismissed the story.

Annette Gordon-Reed proved it. She had long pondered Jefferson and Hemings. As a senior at Dartmouth she wanted to write her history thesis on the subject, but her professor nixed the idea. In 1997, while a professor at New York Law School, she wrote Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy outlining the evidence.

A year later DNA tests vindicated her. They showed that Jefferson almost certainly fathered Hemings’ children. In 2008 Gordon-Reed delved further into their family in The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family. This biography of Sally and her relatives was a magisterial feat. It blew up long-standing beliefs about slavery. It changed the way Monticello approached its past, and it forever altered how Americans see the iconic Jefferson.

Hemingses of Monticello became one of the most honored books in publishing history. It won 16 awards. It was only the third book to receive the National Book Award for history and the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction. Gordon-Reed became the first black writer to win the Pulitzer for history. Within two years of its publication, President Barack Obama awarded her the National Humanities Medal. The MacArthur Foundation gave her its so-called genius award fellowship, and William & Mary (Jefferson’s alma mater) awarded her an honorary degree.

“Annette Gordon-Reed is the preeminent scholar on Sally Hemings and the Hemings family of Monticello,” says Leslie Greene Bowman, the president of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. “No one has done more to bring their stories out of the shadows and into public dialogue. Annette’s work illuminates the stories of one enslaved family at Monticello. It holds a mirror on America today, asking us to remember and learn.”

Her work illuminates the stories of one enslaved family at Monticello. It holds a mirror on America today.”

Gordon-Reed has long been one to upend the status quo. As a first-grader in East Texas she left the all-black school where her mother taught to become the only black student in a white elementary school. At Dartmouth she served on a committee searching for ways to hire more black faculty. Now a professor at Harvard Law School, she served on the College’s board of trustees from 2010 to 2018. —James Zug ’91

#17 Basil O’Connor, class of 1912

Humanitarian

Basil O’Connor asked everyone in America to spare a dime. That’s how he conquered polio. A lawyer and longtime confidante of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, O’Connor’s true gift lay in marketing and organizational management.

“His accomplishment was organizational, it was humanitarian, it was medical, and it will always stand as a hallmark of the advance of medical science,” wrote March of Dimes archivist David Rose in his book, Friends and Partners: The Legacy of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Basil O’Connor in the History of Polio.

O’Connor’s lifelong crusade began in 1927 when he became head of the Warm Springs Foundation, energizing the rural Georgia spa where FDR went for therapy. After serving on FDR’s brain trust of advisors in 1932, O’Connor, at FDR’s request, led the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, better known as the March of Dimes.

A snappy dresser with slicked-back hair who always tucked a carnation in his lapel, he looked like tough-guy movie star Humphrey Bogart. “I was never a public do-gooder and had no aspirations of that kind,” said O’Connor. “But once a crisis demanded action, I started enjoying it.” He conjured up revolutionary fundraising schemes that are now commonplace. He created awareness through mass-market advertising featuring heartrending photos of disabled children. He convinced stars such as Bing Crosby and Ginger Rogers to make fundraising pitches on radio.

The brilliance of the March of Dimes lay in amassing massive sums through tiny gifts. When the campaign launched in 1938, Americans sent an avalanche of 2,680,000 dimes to the White House. Ultimately more than $500 million went to fight polio.

In 1950, five years before Dr. Jonas Salk’s vaccine was first used, O’Connor’s fight against the paralyzing disease became personal—polio killed his daughter. Friends said the tragedy made the autocratic O’Connor more compassionate.

Beyond his marketing skills, he originated the model for today’s charitable health organizations, creating more than 3,100 centrally controlled local fundraising chapters. Dozens of other nonprofits saw his amazing successes. They reorganized themselves around his model and eagerly adopted his money-raising tactics.

O’Connor also made strategic decisions that focused scientific research on the polio virus. “He was one of the best investors ever,” says former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers. By targeting millions of dollars in that direction, O’Connor sped the cure.

As head of the American Red Cross in the late 1940s, O’Connor expanded his humanitarian efforts, raising funds to combat birth defects and arthritis. He remained president of the March of Dimes until his death in 1972 at the age of 80. —C.J. Hughes ’92

#18 Sylvanus Thayer, class of 1807

Superintendent of West Point

He lived like a monk. He was punctual, and he had no vices. No wonder President James Monroe appointed Thayer superintendent of West Point in 1817. It was a failing institution with lax academic and moral standards. Thayer, who attended the academy after Dartmouth, came to Monroe’s attention because he planned and directed the defense of Norfolk, Virginia, during the War of 1812. The British captured many coastal forts, but not Thayer’s, and Uncle Sam rewarded the stalwart young engineer by sending him to Paris for advanced training. During his 16-year tenure at the academy, he became the embodiment of its motto: “Duty. Honor. Country.” A stern, yet beloved, leader with ramrod posture and piercing blue eyes, Thayer transformed West Point into the nation’s first engineering school while insisting on strict discipline. At age 82 he gave Dartmouth funds to establish its own such school in 1867 and helped select its leader, Robert Fletcher, ensuring that the Thayer School of Engineering would also meet his Olympian standards.

#19 Michael Arad ’91

Architect

Growing up in Jerusalem, Arad lived with the threat of terror every day. He loved to visit Israel’s national hilltop cemetery for its beauty, silence, and forested grounds. A U.S.-Israeli citizen, he served for three years in Israel’s army after his first year at Dartmouth. “I never thought about not doing my military service,” he said. On 9/11 Arad, now an architect, was living in the East Village and saw the second plane explode into the South Tower. Witnessing the horror made him begin to draw sketches and create mockups of a memorial—even before a competition was announced. A lone visionary, Arad worked without a team or partner. Judges chose his Reflecting Absence design for the World Trade Center Memorial over 5,200 other entries. His goal? To create a place where people could “feel a sense of community and compassion and stoicism and courage,” he said. Arad recently unveiled a permanent memorial to the “Emanuel Nine,” the victims of the 2015 Charleston, South Carolina, church shootings.

#20 Albert Bickmore, class of 1860

Naturalist and Museum Founder

Born into a poor family on the Maine coast, Bickmore had a treasured childhood moment—being allowed to hold a book on natural history. He loved collecting specimens on the shore and in the woods. After college he trekked in Siberia and East Asia and penned Jules Verne-style true-life travelogues with headings such as “To the Land of the Cannibals,” “Pits for the Rhinoceros,” and “A Boiling Pool.” He watched a mentor start a Boston zoology museum and—believing museums should be temples of science, art, and history, not the slap-dash affairs that many U.S. museums were at the time—he conceived and founded the American Museum of Natural History in 1869. He raised funds from financier J.P. Morgan and Teddy Roosevelt’s philanthropist father. A bold orator, Bickmore held the radical belief that museums should support public education. Science classes were a rarity in schools then, and Bickmore gave lectures to almost 20,000 teachers using high-tech tools such as stereopticons and lantern slides, a pre-electric PowerPoint. Museum curators across the country marveled. Following his lead, they forever changed the scope and purpose of museums and education.

#21 Fred Rogers ’50

TV Personality

Rogers was an ordained Presbyterian minister who said he never wanted to be a preacher. In truth, this unassuming, gentle man had one of the nation’s most influential pulpits: For 33 years he hosted Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, the PBS show he created that taught children lessons in kindness, compassion, and love. “The whole idea is to look at the television camera and present as much love as you possibly could to a person who needs it,” he once said. In all 895 episodes his message was the same: “You are special, and so is your neighbor.” The epitome of modesty and virtue, Rogers neither drank nor smoked. He was a vegetarian. “I don’t want to eat anything that has a mother,” he once said. He rose every day at 5 to swim, and he napped every day, too. For 30 years his weight of 143 pounds remained the same. He believed that number stood for “I love you,” because there is one letter in “I,” four in “love,” and three in “you.” His sweater, a symbol of his warm embrace, is in the Smithsonian.

#22 Grant Tinker ’47

TV Producer and Executive

“First be best, then be first” was Tinker’s motto. During a career that spanned a half-century in radio and TV, this genial media pioneer produced programs unlike any ever broadcast. His 1960s drama I Spy made its black and white heroes equals. The Mary Tyler Moore Show of the 1970s depicted a single career woman who didn’t need a husband to be happy. (Its star, his wife of the same name, said Tinker “uniquely understood that the secret to great TV content was freedom for its creators and performing artists.”) Hill Street Blues in the 1980s used cinéma vérité to depict life in a hurly-burly urban police station. As CEO and chairman of NBC, he led his lagging network to first place with hits whose quirky characters seemed like next-door neighbors. Always self-effacing, Tinker lavished credit for his success on others, saying, “I had the good luck to be around people who did the kinds of work that audiences appreciate.”

#23 E.E. Just, class of 1907

Biologist

“Just Too Early” might have made a fitting epitaph for this groundbreaking biologist who pioneered our understanding of cellular behavior. His study of healthy cells laid a strong foundation for sickle cell anemia, leukemia, and cancer research. Phi Beta Kappa at Dartmouth and the only magna cum laude graduate in his class, Just was denied the honor of giving a Commencement speech. Because he was the only black student in his class, the College decided it would have been embarrassing to let him play such a prominent role. After nearly dying of typhoid as a child, he had to teach himself how to read and write again. When he was 16 his mother sent him from Charleston, South Carolina, to a New Hampshire boarding school—without knowing if he would be admitted. One of the first black students to earn a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, Just did most of his research and teaching in Europe because of racism at home. In 1940 he was briefly imprisoned by the Nazis. Freed through the intervention of the U.S. government, he returned home ailing and died soon thereafter of cancer, his already rich career cut too short.

#24 Rob Watson ’84

Environmentalist

An Eagle Scout, black belt, mountaineer, and crew racer, Watson has always been a leader. “We are either going to be losers or heroes,” he said. “There’s no room anymore for anything in between.” The father of Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), he started the movement in 1993 to create environmentally conscious structures. He devised the Green Building Rating System guidelines that require eco-friendly components, construction, and building management. LEED has proven that green buildings can be more cost-efficient to build and operate than old-style structures. Since 1998 more than 80,000 projects have been built to its standards, saving vast amounts of energy and resources. “Rob Watson was seminal in LEED’s creation,” says Rick Fedrizzi, former CEO of the U.S. Green Building Council. “It has transformed the real estate market.”

#25 James Nachtwey ’70

Photo Journalist

For more than 35 years acclaimed photographer Nachtwey has crisscrossed the globe to show magazine readers the worst the world has to offer—wars, famine, disaster, pollution, and homelessness. Of his work and that of his peers, he says, “We question the powerful. We hold decision-makers accountable. The chain we help forge links the people we encounter in the field to millions of other individual minds and sensibilities. And once mass consciousness evolves into a shared sense of conscience, change becomes not only possible; it becomes inevitable.” Nachtwey has repeatedly risked his life to capture decisive moments. He was injured by a grenade in Baghdad, shot in Thailand, and had to hide in a Sri Lankan monastery for three weeks until it was safe to flee. Time magazine in 2018 devoted an entire issue to his “Opioid Diaries” documenting that drug epidemic. The world traveler has won numerous honors, including Magazine Photographer of the Year (seven times), World Press Photo Award (twice), and the Robert Capa Gold Medal (five times).

—Profiles 18-25 written by George M. Spencer

Illustrations by Joe McKendry

How We Chose the Top 25

Our efforts to rank the College’s most influential alumni—an idea inspired by the human fondness for lists, rankings, and the arguments that ensue—required deep digging. For 10 years (no, that’s not a typo) we drew up lists. We deliberated. We wrestled with an ever-growing slate of candidates. Nothing came easy.

In the end, we decided not to decide.

Instead we asked professors to do the rigorous intellectual work and heavy lifting. We called on faculty members from eight disciplines to serve as our panel of experts. DAM board member James “Jed” Dobson of the English department embraced the role of chairman, undaunted by the task of bringing faculty members to consensus. Joining him were Leslie Butler (history), Marlene Heck (art history), Russell Muirhead (government), Adina Roskies (philosophy and psychological and brain sciences), Bruce Sacerdote ’90 (economics), James Whitfield (physics and astronomy), and associate dean of arts and humanities Barbara Will (English).

Dobson asked each to submit by email his or her own top 25 after considering a list of about 100 candidates winnowed down by DAM editors from a much larger list. Panelists were also allowed to introduce additional candidates. When the lists arrived, Dobson tallied the points with the help of Sacerdote and produced a shortlist worthy of debate—and dinner.

On a November night in 2017 the panel convened with the editors at the Paganucci Lounge. The discussion quickly focused on the difficult issues. How is it possible to weigh the established legacy of a long-dead alum with the ongoing achievements of a living alum? What does the word influential mean? Should having a negative impact be cause for elimination?

Consensus quickly developed that a ranked alum’s influence should be positive. Panel members were relieved when they realized few alums would be dinged on that basis. “We may not have a Hitler, but we do have some people who I think bring discredit to the institution. I will be upset if the list includes someone who does that,” said Roskies.

“I was struck by a guideline suggested by the editors that we should ask ourselves if the world would be different if the alum hadn’t existed,” said Heck. “That’s why weighing contemporaries is so hard.”

At this point the conversation veered into the possibility of having multiple lists: living alumni, the dead, a separate ranking for women. This was quickly squashed by the editors. One list to serve them all. If the list skews white, male, and 19th-century, so be it. No revisionist history, please.

What about living alums who are celebrities—people who are famous for being famous? Butler observed that some would say Kim Kardashian is an influential cultural figure because of her millions of Twitter followers. “Not a quantitative metric in my view,” she quickly added.

Muirhead chimed in, observing it’s not enough to be famous. One must have impact, too. “In political philosophy we distinguish between people who rise to positions of great notoriety by responding to the existing shape of public opinion with exquisitely calibrated instincts,” he said. “Then there are those who create a new shape and in the most extreme cases would be seen as heroic—such as Lincoln, who inserted the opinion that slavery was bad into a debate about expanding slavery into the territories.”

Will added that the humanities value people who contribute “a deepening of our aesthetic and understanding of the world. I’m thinking of Robert Frost [class of 1896], a vernacular poet, but not until one or two generations later did we realize he was a great American poet.”

The panel grew self-conscious about its task, aware that this public enterprise was more than an academic exercise. Several professors worried about “the optics” of the list. How would it look, one wondered, if an alum who hadn’t graduated topped the list? (The College considers anyone who matriculates to be an alum.) What if a certain world-famous children’s author were ranked higher than a globe-straddling statesman?

Ultimately, the panel got around to the hard work of culling and ranking. No one held back. “I feel my soul shrinking,” said Will in response to a colleague’s support of one candidate. “So-and-so ranked above so-and-so just seems crazy,” a frustrated professor grumbled. “This is hard,” sighed another.

Dinner was served and so were passionate endorsements. Butler made a case for including Annette Gordon-Reed ’81 (No. 16). “She completely, fundamentally changed how we think about Jefferson,” Butler contended. Architectural scholar Heck insisted that 9/11 Memorial architect Michael Arad ’91 (No. 19) made the definitive contribution to America’s processing of that day. Will articulated the lasting contributions of Louise Erdrich ’76 (No. 13) to literature and Native American studies. “She is one of the most incredible writers living today,” Will said.

Whitfield later addressed a matchup between the arts and science: “The work of Ed Lorenz ’38 (No. 11) is particularly timely as we consider the future of the earth’s climate. This makes him one of the top five on my list, although I wouldn’t place him higher than Frost because of his lack of recognition in the broader public sphere.”

After dessert and coffee, each professor wrote a new list based on all they’d heard, leaving it up to DAM to run the numbers and the final rankings. The panelists waved goodbye and headed off—no homework for this group. The editors calculated the results, presented here for the first time.

Did the panel do a good job? Its list is well balanced: six come from politics, eight from the arts, and 11 from science and medicine. Despite disagreements, 21 of the final 25 got votes from all eight panelists, and the top 13 garnered more than 100 points, with Daniel Webster, class of 1801, atop the leaderboard with 196. DAM leaves the ultimate decision up to you, our reader, to decide. We believe it’s all arguable—and we welcome an ongoing debate.

—The Editors

Additional Resources on the Top 25

#1 Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster: The Man and His Time, Robert Remini (Norton, 1997)

Daniel Webster, Irving Bartlett (Norton, 1978)

“Daniel Webster: A Resource Guide”

“Daniel Webster,” U.S. Senate

#2 Theodor Geisel

Theodor Geisel: A Portrait of the Man Who Became Dr. Seuss, Donald Pease (Oxford Univ. Press, 2010)

The Cat Behind the Hat, Caroline Smith (Andrews McMeel, 2012)

Secrets of the Deep—The Art of Dr. Seuss, Caroline Smith (Chase Group, 2010)

Theodor Geisel: A Portrait of the Man Who Became Dr. Seuss, Donald Pease (Oxford Press, 2016)

“Children’s Friend,” The New Yorker, Dec. 17, 1960

#3 Robert Frost

Robert Frost: A Biography, Jeffrey Meyers (Houghton Mifflin, 1996)

The Life of Robert Frost: A Critical Biography, Henry Hart (Wiley Blackwell, 2017)

“Robert Frost,” Poetry Foundation

The Robert Frost Society

President Kennedy’s Remarks at Amherst College, Oct. 26, 1963

#4 Robert Smith

Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA World Services, 2002)

Children of the Healer: The Story of Dr. Bob’s Kids, Bob Smith (Hazelden, 1994)

Bill W. & Dr. Bob, Samuel Shem (Samuel French, 2010)

Bill W.: A Biography of Alcoholics Anonymous Cofounder Bill Wilson, Francis Hartigan (Thomas Dunne, 2000)

“The Alcoholic Stockbroker and the Forgotten Doctor,” The Atlantic, April 2014

“Secret of AA: After 75 Years, We Don’t Know How It Works,” Wired, June 2010

#5 Salmon P. Chase

Salmon P. Chase: A Biography, John Niven (Oxford Press, 1995)

Salmon P. Chase: A Life in Politics, Frederick Blue (Kent State Press, 1978)

“Salmon P. Chase (1803-1873),” Mr. Lincoln’s White House

“Salmon P. Chase,” Ohio History Central

“Salmon P. Chase and the Politics of Racial Reform,” Herman Belz, Summer 1996, Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association

#6 Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens and Negro Rights, Milton Meltzer (Ty Crowell, 1967)

Thaddeus Stevens, Hans Trefousse (UNC Press, 1997)

Thaddeus Stevens: Scourge of the South, Fawn Brodie (Norton, 1959)

“Remarkable Radical: Thaddeus Stevens,” Humanities, Nov/Dec 2012

#7 Nelson Rockefeller

On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller, Richard Norton Smith (Random House, 2014)

The Life of Nelson A. Rockefeller, Carey Reich (Doubleday, 1996)

The Imperial Rockefeller, Joseph Persico (Simon & Schuster, 1982)

I Never Wanted to be Vice President of Anything, Sam Roberts and Michael Kramer (Basic Books, 1976)

The Rockefeller Archive Center

#8 Owen Chamberlain

Owen Chamberlain, 1920-2006: A Biographical Memoir, Herbert Steiner, National Academy of Sciences

“Owen Chamberlain—Biographical,” The Nobel Prize

“Owen Chamberlain,” Atomic Heritage Foundation

“Obituary of Owen Chamberlain,” Physics Today, March 2006

#9 George Perkins Marsh

Man and Nature, George Perkins Marsh (Scribner & Co., 1864)

George Perkins Marsh, National Park Service

“The Polymath from Vermont,” Virginia Quarterly Review, Winter 1999

#10 Samuel Katz

“Samuel Lawrence Katz, MD,” interview, Pediatric History Center, March 7, 2002

“Samuel Katz, M.D., ’50: Vaccine Ambassador,” Dartmouth Medicine, Summer 2009

Samuel L. Katz, MD, Duke Human Vaccine Institute

“Measles Outbreak Hits Home for Trailblazing Doctor,” WTOP, Feb. 19, 2015

#11 Edward Lorenz

Essence of Chaos, Edward Lorenz (University of Washington Press, 1993)

“When the Butterfly Effect Took Flight,” MIT Technology Review, Feb. 22, 2011

“Edward Lorenz: Pioneer in Chaos Theory,” The Washington Post, April 17, 2008

“Ed Reckoning,” DAM, Sept/Oct 2006

“Pinball Chaos,” The Mathematical Tourist, Dec. 10, 2013

#12 C. Everett Koop

“The C. Everett Koop Papers,” U.S. National Library of Medicine

The C. Everett Koop Institute at Dartmouth

“It’s In the Mail,” The Ultimate History Project

“Doctor, Not Chaplain: How a Deeply Religious Surgeon General Taught a Nation About HIV,” The Atlantic, March 4, 2003

“9 Things You Should Know About C. Everett Koop,” The Gospel Coalition, Feb. 25, 2013

#13 Louise Erdrich

“The Continuing Saga of Louise Erdrich,” American Indian Magazine, Winter 2016

“Louise Erdrich,” PEN/Faulkner, Episode 53

“A Timely Novel of Anti-Progress by Louise Erdrich,” The New York Times, Nov. 21, 2017

“Louise Erdrich,” Poetry Foundation

“Earth Mother,” DAM, Jan-Feb 2015

#14 George Bissell

The Prize, Daniel Yergin (Simon & Schuster, 1990)

“How the History of Petroleum Was Made in New England,” New England Historical Society

“George Bissell: Oil Industry Patriarch,” Oil 150, July 16, 2007

“First American Oil Well,” American Oil & Gas Historical Society

“George Henry Bissell…Oil’s Patriarch,” Petroleum History Institute

#15 George Snell

Making Mice, Karen Rader (Princeton Univ. Press, 2004)

“George D. Snell Facts,” The Nobel Prize

“George D. Snell Nobel Lecture,” The Nobel Prize, Dec. 8, 1980

George Davis Snell, 1903-1996: A Biographical Memoir, N. Avrion Mitchison, National Academy of Sciences, 2003

“George Davis Snell, 92, Dies; Won Nobel for Genetics Work,” The New York Times, June 8, 1996

#16 Annette Gordon-Reed

The Heminges of Monticello: An American Family, Gordon-Reed (W.W. Norton, 2008); Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy (Univ. of Virginia Press, 1997)

PBS Frontline interview, Jan. 31, 2001

“Pulitzer Prize Winner Annette Gordon-Reed on Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson,” Rhae Lynn Barnes, U.S. History Scene, April 10, 2015

“Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account,” www.monticello.org

“You Can’t Let Your Emotions Overtake You So Much That You Can’t Do the Work,” Colleen Walsh, The Harvard Gazette, May 2, 2017

#17 Basil O’Connor

Friends and Partner: The Legacy of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Basil O’Connor in the History of Polio, David W. Rose (Academic Press, 2016)

Polio: An American Story, David M. Oshinsky (Oxford Univ. Press, 2005)

A Summer Plague: Polio and Its Survivors, Tony Gould (Yale Univ. Press, 1995)

“FDR’s Secret Weapon,” DAM, May/June 2008

“Marching to a Different Mission,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, Spring 2008

#18 Sylvanus Thayer

Duty, Honor, Country: A History of West Point, Stephen Ambrose (JHU Press, 1966)

West Point, Thomas Fleming William Morrow (1969)

“Big Picture: Sylvanus Thayer of West Point”

“Sylvanus Thayer: The Man Who Made West Point,” American Heritage, June 1978

#19 Michael Arad

Sixteen Acres: The Outrageous Struggle for the Future of Ground Zero, Philip Nobel (Metropolitan Books, 2005)

Power at Ground Zero: Politics, Money, and the Remaking of Lower Manhattan, Lynne Sagalyn (Oxford Univ. Press, 2016)

“The Breaking of Michael Arad,” New York Magazine

“Architect and 9/11 Memorial Both Evolved Over the Years,” The New York Times, Sept. 1, 2011

#20 Albert Bickmore

Travels in the East Indian Archipelago, Albert Bickmore (John Murray, 1868)

“Albert Bickmore,” Harvard Magazine. Sept/Oct 2008

#21 Fred Rogers

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, Mark Collins (Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, 1996)

I’m Proud of You: My Friendship with Fred Rogers, Tim Madigan (Create Space, 2012)

The Simple Faith of Mister Rogers: Spiritual Insights from the World’s Most Beloved Neighbor, Amy Hollingsworth (New Edition, 2007)

“Saint Fred,” The Atlantic, Nov. 2015

“Can You Say…Hero?” Esquire, April 2017

#22 Grant Tinker

Tinker in Television: From General Sarnoff to General Electric, Grant Tinker (Simon & Schuster, 1994)

Inside Prime Time, Todd Gitlin (Univ. of California Press, 2000)

They’ll Never Put That on the Air: An Oral History of Taboo-Breaking TV Comedy, Allan Neuwirth (Allworth Press, 2006)

“Starting Over: TV’s Grant Tinker,” The New York Times, Oct. 25, 1997

#23 E.E. Just

The Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just, Kenneth Manning (Oxford Univ. Press, 1985)

“Just and Unjust: E.E. Just,” Genetics, Aug. 2008

“E.E. Just,” ASBMB Today, Feb. 2010

#24 Rob Watson

“Father of LEED Takes on China and India,” Mother Nature Network, March 2010 (originally published in Plenty, Feb. 2008)

Watson’s blog: Radical Confidence

U.S. Green Building Council

#25 James Nachtwey

Inferno (1999) and Memoria (2019), James Nachtwey (Phaidon Press)

Pietas, James Nachtwey (Contrasto, 2012)

“James Nachtwey: How Photography Can Change the World,” Time, Feb. 3, 2015

“TED Talks: James Nachtwey”

Witness, James Nachtwey’s website