For most of the DOC’s history, the out-of-doors has been close enough at Dartmouth to speak for itself. But Hanover is now in the middle of one of the most rapidly developing areas in the Northeast. The wilderness of 1909 has physically diminished, and has receded as well from the spirit of the College and the perception of its students. Dartmouth is fast approaching a par with other schools, where experience in the outdoors will no longer occur automatically, but only as a result of commitment to its educational value.

—H. Bernard Waugh Jr. ’74,

from the preface of Reaching That Peak (1986)

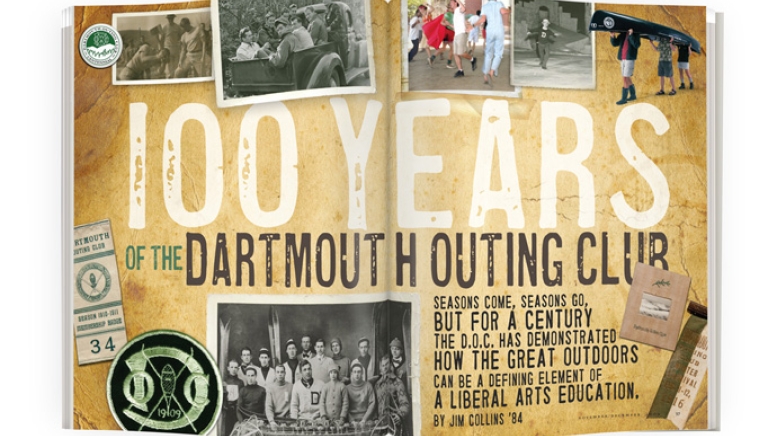

Nearly 25 years have passed since Bernie Waugh raised a quiet alarm in his foreword to the DOC history by David Hooke ’84. And although the cultural forces he worried about have become even more pronounced, the club has withstood all manner of shifts in public fashion, growing into an umbrella organization for a dozen affiliated groups ranging from the traditional Cabin & Trail (emphasis on hiking) to the environmental advocacy of the used-cooking-oil-fueled Big Green Bus. Founded in 1909 “to stimulate interest in out-of-door sports,” the DOC is the oldest and largest collegiate outing club in America. But the current environment for outing clubs anywhere has never seemed less hospitable.

The hypothetical narrative is tempting: A venerable college institution drifts into the 21st century with diminishing focus and energy. Students, increasingly busy with academics and a wired new world, can no longer find enough free time to keep up basic trail work and cabin maintenance. In an era of risk-averse College lawyers and an ever-more-suburban population, an institution founded on snowshoeing and skiing finds itself in serious danger of becoming irrelevant.

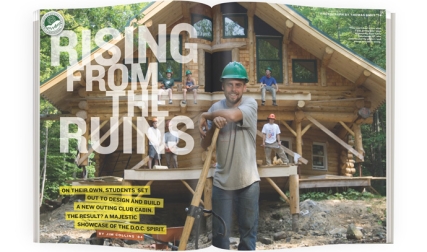

But then in the summer of 2004, following a demoralizing period of instability, the renaissance of the DOC begins. The new director, a legend within the DOC, reinvigorates the club by returning it to its roots and giving the students the reins. Within four years Cabin & Trail crews build new shelters at Velvet Rocks and on Moose Mountain and—on the site of the ruined Harris Cabin in Etna—the most impressive structure the DOC has constructed in seven decades. Students add a greenhouse and a timber-frame sugarhouse to the organic farm on Route 10 north of campus. Paddlers and climbers pull off logistically complicated expeditions from Saskatchewan to South America to Africa to the Alps. Interest burgeons in kayaking classes, winter gear rentals and the annual 50-mile hike. Dartmouth’s ski team dominates the Eastern carnival circuit and wins its first NCAA championship in 30 years. Nearly 700 students apply to lead first-year trips. The Outing Club, now in the midst of a yearlong celebration of its centennial, suddenly appears as vital and integral to the College as it has ever been.

The narrative could fit—all of those particular facts line up—but it would border on mythology. The truer story is not of heroes or death and rebirth but of evolution. The energy bubbling out of Robinson Hall these days is unmistakable, and it prompts a question: In this day and age how is it that an outdoor club continues to be a defining part of a liberal education?

A century ago Fred Harris, class of 1911, urged fellow students to join in a ski and snowshoe club to take advantage of Dartmouth’s location rather than complain about it. From the beginning—unlike at nearly every other college and university that followed in Dartmouth’s path—students here conceived and organized and ran their own club. In those early years Dartmouth students helped outdoor clubs get off the ground at Yale, Colgate, Tufts and the University of Vermont and routinely advised a half-dozen others.

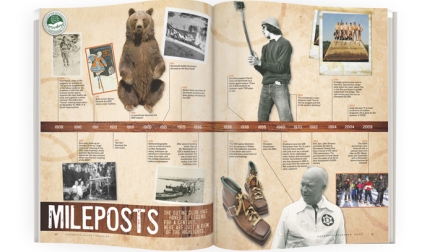

The national reputation of the DOC soon spread into every corner of the outdoor world. In 1920 a National Geographic article by Harris titled “Skiing Over the New Hampshire Hills” led to an unprecedented spike in applications from around the country, and Dartmouth was forced to adopt a selective process of admission for the first time. Fox Films and LIFE magazine and other publications described a distinctive, outdoorsy “Dartmouth spirit” and created a mystique reinforced by the school’s hill-winds song lyrics of Richard Hovey, class of 1895, and the woolly images of College photographer Adrian Bouchard ’41. Dartmouth made its name in competitions and brand-name ascents. In 1924 John Carleton ’22, who honed his jumping skills in the DOC, became the College’s first representative at the winter Olympics—a Dartmouth tradition that has continued unbroken through every winter Olympics since. The DOC hosted the nation’s first downhill college ski races and the first intercollegiate figure skating competition. It filled the ranks and provided lead training of the 10th Mountain Division, the U.S. Army’s elite World War II mountaineering corps. It sponsored the first collegiate Woodsmen’s Weekend, winning eight of the first 10 competitions. It became a national power in kayaking. In 1963 more than a quarter of the 19 members of the first U.S. expedition on Everest came out of Dartmouth’s mountaineering club.

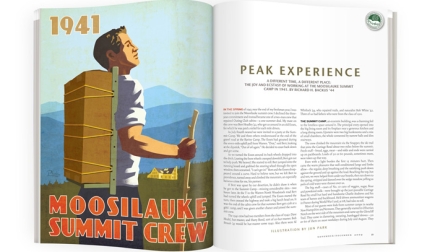

Dartmouth students helped build and maintain a network of outdoor facilities unmatched by any other college: a statewide chain of cabins and shelters, a rustic mountain lodge and a lift-service ski area (Middlebury’s Snow Bowl remains the only other college-owned area like it in the country). DOC members skated on a college-maintained pond and hunted in a remote 27,000-acre tract of college-owned forest. They walked from the center of campus and within minutes slipped onto the Appalachian Trail or into the Connecticut River in a canoe or skied a groomed championship-caliber course. Within a 20-minute drive they found a choice of Class II-III whitewater or some decent trout fishing.

Inspired by student energy, the DOC became marked by go-for-it optimism, a fondness for songs and rituals and a taste for epic adventure. Members in 1911 created the definitive Winter Carnival, complete with majestic snow sculptures, downhill canoe races and polar bear swims. Nine years later the Ledyard Canoe Club reprised John Ledyard’s dramatic 1773 departure from the College with what has become an annual 210-mile trip down the Connecticut River to Long Island Sound. In the fall of 1935 the DOC’s signature freshman trips began introducing incoming students to Dartmouth’s rugged North Country setting and, over time, to the camp-classic film Schlitz on Mount Washington, midnight ice-cream raids and the “Salty Dog Rag.”

Legends passed down to each new generation of Chubbers. (Even the word “Chubber” is part of the lore—it first appeared in a 1933 article in The Dartmouth lampooning the peculiar student who “slept on rocks” and had “the odor of woodsmoke about his clothes.”) Ghosts lived in logbook entries and silly awards and stories told and retold: of Dick Durrance ’39 winning the hell-bent Inferno ski race over the lip and down the headwall of Mt. Washington’s Tuckerman Ravine; of ’62 classmates and canoeists Pete Knight and Jon Fairbank riding an April flood from Hanover to the sea in less than 34 hours; of the legendary slalom kayak skills of Dana Chladek ’85; of Doc Benton haunting the flanks of Mount Moosilauke to this day. A collective memory infused the club, creating a rich sense of continuity and identity.

Of course, even institutional memory can be selective.

The fuller story of the DOC, not burnished to smooth shine, is far from continuous. “There’s always been an ebb and flow within the Outing Club: growth, stalling, then a spark again,” says Kevin Peterson ’82, a woodsmen’s team advisor who has served the DOC in several volunteer capacities since graduating. “That’s just the nature of a student-led organization.”

In more than 100 years of fluctuating student activity, with varying degrees of institutional and external pressures and changes in the natural environment, the story of the DOC has never followed a clear narrative arc. There never was a heyday, and reports of its death have always proved premature.

Under John Sloan Dickey ’29, the prototypical outdoors-loving Dartmouth president who would jump into a Jeep during bug season and drive to the Grant to go fly-fishing, the percentage of incoming students going on freshman trips reached only half of what it would later be under President James O. Freedman, who spoke far more about Dartmouth’s life of the mind than he did about the out-of-doors.

The club’s essential lack of formal infrastructure made it susceptible to ebbs and flows, but it also gave the club a certain nimbleness. Students had the freedom to adapt quickly and energetically to the times.

In the late 1930s Swiss coach Walter Prager was making Dartmouth the absolute center of the new sport of downhill skiing, just as the Boots & Saddles Club saw interest in skijoring and polo drying up and as the Connecticut River was becoming so polluted that Ledyard canoeists would suspend their annual downriver trip for 20 years. (The canoe club would go practically dormant until new club advisor Jay Evans ’49 arrived in the early 1960s and turned the club toward kayaking.) During World War II gas rationing limited hiking trips to all but short day trips and overnights close to campus. After the war legendary woodcraft advisor Ross McKenney was disgusted by the students’ lack of interest in using the club’s shelters and cabins. Suspecting it stemmed from a lack of confidence in basic woods skills, McKenney came up with the idea of a woodsmen’s team and competition. The Ravine Lodge’s original use as a ski center was short-lived; at one point it was unsuccessfully offered to the Appalachian Mountain Club for a dollar, then was shut down in winter. Cabins deteriorated and were abandoned or burned. Students formed new clubs (bicycling, snowboarding) and dropped others (fishing team) as interest shifted. In that way the DOC has always mirrored society while being out ahead of it.

It was true in the early part of the 20th century, when Dartmouth students were showing an emerging affluent class how the outdoors could be used for recreation and made competitive. It was true in the 1950s, when the country realized it needed science to understand its environment, while DOC students had long been engaging faculty in the study of extreme weather systems and sub-alpine tundra and local wetlands. It was true in the early 1970s, when it became clear that science needed to be coupled with policy and regulation, and Chubbers had already fought for the creation of something utterly new: an academic environmental studies division within an outing club, with a political bent and a science lab in Robinson Hall.

That nimbleness has been evident in the face of changes on campus as well. During the College’s transition to coeducation the DOC brought women in faster and more thoroughly than any other student organization. The integration required early pioneers—strong women who didn’t shy away from the club’s macho culture. Skier Nancy Pease ’82 arrived from Alaska and immediately started kicking butts running up Moosilauke. Her classmate Sally McCoy ’82 was handed a woodsmen’s team T-shirt as a freshman with the words “Woods Pussy” on the back. “Like hell I’m going to wear that,” McCoy declared. She had a different T-shirt made up for the Cabin & Trail director that had “Wood Pecker” on the back. And once they were part of the culture, women started changing it. “But the thing was,” says McCoy from her CEO desk at water bottle manufacturer CamelBak Products, “the DOC was organized by competence, not gender.”

She and a handful of other women of that era came in with natural authority and were readily given leadership positions within the club. Viva Hardigg ’84 would come back to her fourth-floor room in Wheeler after competing in a Carnival race and have to maneuver two pairs of skis through a hallway full of men in boxer shorts hooting at her. “The Outing Club,” she recalls, “was often way ahead of other parts of campus.”

She became the DOC’s first female president in 1985, just as her classmate Hooke began writing Reaching That Peak: 75 Years of the Dartmouth Outing Club.

Despite the excitement of a new guard, outside of Dartmouth the mystique of the DOC had started to lose some of its luster. The environmental movement had touched off a wave of outdoor interest across the country. For-profit wilderness programs were providing the kind of training and experiences that had previously been found only at Dartmouth and a handful of other places. The College had long since lost its place atop the ski world to the University of Vermont in the East and to Denver and Colorado in the West. The NCAA did away with ski jumping altogether, and Dartmouth tore down its old jump for liability reasons. In the national media academic rankings, campus controversies and The Dartmouth Review supplanted the College’s outdoorsy image.

At the same time the culture at Dartmouth was changing. As the College’s hierarchy expanded the DOC director reported not to the College president, as he had under Dickey, or the dean of the college, but to a sub-dean in student life. And as former director Earl Jette ’55 notes, “Every layer gets a little less enthusiastic when you ask for something.”

Meanwhile, the administration became more concerned about club activities. It became less casual, more worried about potential lawsuits, less comfortable giving students autonomy. The death of kayaker Mimi LeBeau ’92 on a Ledyard trip in 1989 sparked a push for better safety procedures.

The club lost some of its maverick energy in the process—the days of throwing a few packs in the back of a van and taking off were over—but students accepted the responsibility. Each division put rigorous training and safety protocols in place, and a succession of leaders internalized the push for constant assessment and improvement. A safety review board made up of students, administrators and experts from inside and outside the College met regularly to review trip proposals, discuss potential issues and conduct postmortems. A system of leadership training evolved across the DOC, creating a ladder from apprentice to assistant leader to trip leader to club officer. Along with learning the skills of using a chainsaw and making a bow rescue in a kayak, trip leaders now had to get first-aid certification and risk management training, plus an awareness of both objective and subjective dangers: Are there worrisome signs in the snow conditions? How fast is the weather changing? Is there someone in the group who’s being pushed too hard? The administration made an uneasy deal with the students: Prove to us you’re responsible and we’ll give you the responsibility to do what you like.

But the stakes were rising. As current DOC general manager Rory Gawler ’05 puts it, “The only way an administration knows how to manage or decrease risk is from the top down.” Cornell and Middlebury, faced with similar worries, made their clubs more institutional. At Sterling and Prescott colleges and the University of New Hampshire outing club students received more of their training from professional staff and faculty and took degrees in outdoor education. Wilderness training programs such as National Outdoor Leadership School (N.O.L.S.) and experiential programs such as Outward Bound were almost entirely staff-directed. Not at Dartmouth. Here the administration makes a request, and the DOC says to the students: “Here’s what you need to do. How are you going to get there?”

And the students have figured it out. Every year the DOC safety figures—compared to any other school’s—are off the charts. Last fall students took nearly 1,000 incoming freshmen and 500 others out in the woods for five days during first-year trips (a total of 167,000 program hours) and reported just 19 minor medical incidents, including three previously undiagnosed allergies, a couple of popped blisters and one migraine.

No other outdoor program of similar scale allows students to make the decisions, do the planning and training, create the structure, lead the trips, take the responsibility. “It was clear to us which was the better model,” says Jed Williamson, land program director for the Dartmouth/Hurricane Island Outward Bound program from 1981 to 1984 and a N.O.L.S. board member. “Who would you rather have—someone who had majored in canoe-ology or someone from Ledyard who had led a canoe trip in the Northwest Territories?” Yet the director of the outdoor club at St. Michael’s College in Vermont spoke for many others when he said earlier this year, “I’d be terrified with the Dartmouth model.”

When Jette retired in 2001, taking 30 years of experience with him, and with the DOC model cutting so hard against the grain, the worry among veterans was that Dartmouth would take the responsibility for the organization away from the students.

As two new directors came and went between 2001 and 2004 that worry intensified. Amid the turnover and unclear administrative support there was a growing sense that the vaunted DOC was merely treading water.

The hiring of Andy Harvard ’71 as director of outdoor programs in 2004 appeared like a lifeline. Harvard, a world-class mountaineer with extensive legal and on-the-ground experience in outdoor risk and risk management, seemed unusually well positioned for the times and—except for his last name—a good fit for Dartmouth.

He understood the culture of the DOC and was an eloquent champion of fitting outdoor activities into an educational mission: “In real time, on a mountain that’s cold and hard, on a wild river, you get moments of clarity and certainty that you can’t get in any classroom,” he said. Harvard continued refining safety and training procedures and gave students the wheel. They responded, with new efforts reflecting society’s growing enthusiasm for sustainable systems. Interest in organic farming exploded, and Farm & Field became the fastest-growing division within the DOC, with more than a dozen faculty involved in academic projects. In North Hall students created a super-efficient, carbon-neutral, residential sustainable living center, one of the first to appear on a college campus in this country. “This is the historic moment we’re in,” said Harvard, as the College’s newest affinity house was getting off the ground. The worrisome period of instability in the DOC seemed gone.

By the summer of 2008 Harvard was also gone. His abrupt departure stunned students and threw the outdoor programs office into limbo once again. Students wrote op-ed pieces in The D and The Dartmouth Review and alumni speculated on the club’s Chubbernet listserv that Harvard had been forced out. Jette eddied out of retirement to serve as interim director while yet another search committee formed.

The job description demanded a person who could do it all, not just inspire energy among students in the DOC. The position had evolved into a high-level administrative desk job that included oversight of 14 full-time and numerous part-time and seasonal employees; an NCAA Division 1 ski team; an extensive variety of facilities that include a ski lodge, aging mountain lodge, a score of cabins, boathouse, organic farm, climbing gym, high ropes courses and hiking and skiing trails; an annual operating budget of $2 million; and a dizzying number of restricted and unrestricted endowments totaling close to $19 million. If you took the job thinking it was only about outdoor education or if you focused only on the student program part of it, you weren’t going to last long. If you thought you were going to spend a lot of time in the job outdoors you had another thought coming. Educational vision aside—hell, paperwork aside—you were still responsible for the safety and well-being of hundreds of unsupervised 18- to 22-year-olds during hundreds of thousands of hours spent in some of the most dangerous activities and wild places in New Hampshire and across the planet.

In April, following a prolonged national search, Chubbers breathed out. The College found a director it thinks can guide the DOC into a fair part of its next 100 years, and it found him right on campus: long-time dean and then-acting assistant to the president Dan Nelson ’75.

Nelson, active in Cabin & Trail as a student and steeped in the culture of the DOC, had a stuffed moose head on the wall of his Parkhurst office. He has led a dozen freshman trips, is an accomplished whitewater canoeist, owns a camp in Maine, knows how to handle a fly rod. Just a month before the announcement he returned from a ski traverse on a mountain plateau in Norway. He was planning a coast-to-coast U.S. biking trek. He has the kind of spirit students recognize and respect. During his summer leave terms Nelson worked as a climbing guide on Mt. Rainier in his home state of Washington and on Denali in Alaska. Nelson knows, because he lived it, that the fun and camaraderie and shared sense of accomplishment coming out of the DOC has, for many students, been the most powerful part of their Dartmouth experience.

Just as importantly he has served on a number of outdoor programs advisory and safety committees and is intimately involved with many of the department’s inner workings. “I can’t speak to the search committee’s reason for recommending me,” he says, “but I’d like to think that after nearly 30 years working here I know how to get things done—and how not to get things done.”

Nelson has said he doesn’t want to impose a vision for the club, that his proper role is to allow the students to realize their vision. He said a primary focus would be elevating the visibility of the club on campus.

Student leaders are aware of the need to reach out. They recently created special all-DOC days, for example, to help spread the religion. Once a term the most experienced Chubbers spend a day teaching a whole range of outdoor activities, then put on a huge feed and crazy dance. Many of the newcomers to the events become regulars. Less hard-core students are invited to get up at dawn on Wednesdays to caravan around the Upper Valley in search of diners. The Wolfgang Schlitz Adventure Fund has been created to help cover the costs of two or three student-initiated trips each year for students “regardless of prior involvement but contingent on future involvement” in the DOC. Recent applications include a bike trip across the Middle East and a walkabout in Iceland.

Then there are the first-year trips, which introduce practically an entire class each year to Dartmouth’s out-o-doors. For many freshmen—nervous, insecure, wondering where or if they’ll fit in—the wild costumes, face paint, purple hair and loud music greeting them in front of Robinson Hall create an oddly reassuring welcome. (Can you imagine the same kindness extended to students arriving at Harvard? At MIT?) And for many of them, no matter how suburban or different their backgrounds, a deep impression sets in over the coming days, guided and surrounded only by other students in the College’s extraordinary back yard.

Nelson realizes that while the constituency for outdoor recreation is still primarily affluent and white, attracting minorities and lower-income students to the DOC will ensure its ongoing relevance in an ever more diverse student body and society.

Nelson also brings an understanding of the incoming generation, with its endemic “nature deficit.” He’s seen the relentless ratcheting up of academic standards and the growth of various other opportunities and knows students can’t major in the DOC as they once may have. A typical DOC president might shoot photos for The Dartmouth, study in the physics department, empty dorm recycling bins for the Environmental Conservation Organization, and volunteer at the Tucker Foundation before finishing the day with a few hours online. Nelson has watched it become increasingly difficult for students to find time. He understands the need for shorter trips and activities closer to campus.

The looming opportunity isn’t lost on him, either. More than in any indoor setting at Dartmouth, students in the DOC learn how to work within a group, manage, plan, improvise, be resourceful, make decisions, lead. Whether in the spruce forests of the College Grant or the high peaks of the Andes they absorb an awareness of the environment and what it means to live responsibly.

If the historic moment has to do with stewardship and sustainability, the educational one may have to do with the DOC’s student-driven culture. It may get to the heart of the club’s role in today’s liberal arts, the educational value Bernie Waugh wondered about all those years ago.

DOC members take what they’ve learned into the wider world—to conservation committees and food co-ops and planning boards, to classrooms and boardrooms and R&D labs and public office—and they make a difference.

In the context of a liberal arts education today it’s hard to imagine anything more relevant.

Jim Collins, a former editor of DAM, is the author of The Last Best League.