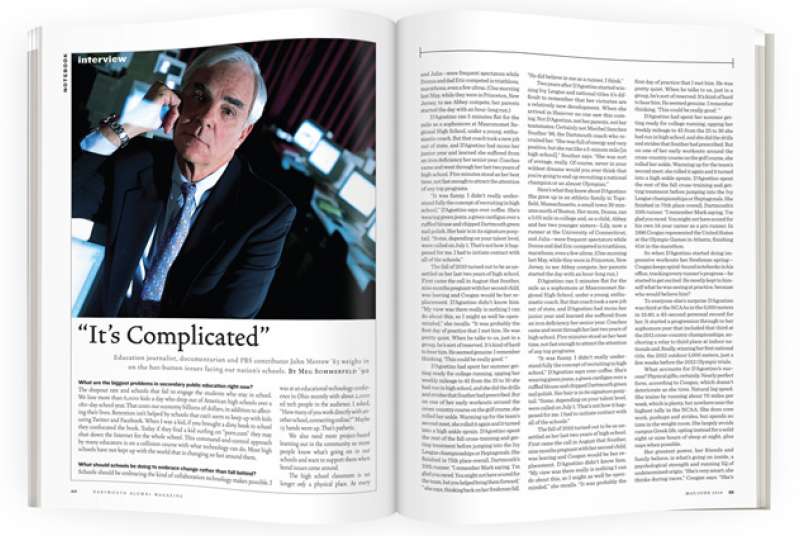

“It’s Complicated”

What are the biggest problems in secondary public education right now?

The dropout rate and schools that fail to engage the students who stay in school. We lose more than 6,000 kids a day who drop out of American high schools over a 180-day school year. That costs our economy billions of dollars, in addition to affecting their lives. Retention isn’t helped by schools that can’t seem to keep up with kids using Twitter and Facebook. When I was a kid, if you brought a dirty book to school they confiscated the book. Today if they find a kid surfing on “porn.com” they may shut down the Internet for the whole school. This command-and-control approach by many educators is on a collision course with what technology can do. Most high schools have not kept up with the world that is changing so fast around them.

What should schools be doing to embrace change rather than fall behind?

Schools should be embracing the kind of collaboration technology makes possible. I was at an educational technology conference in Ohio recently with about 2,000 ed tech people in the audience. I asked, “How many of you work directly with another school, connecting online?” Maybe 15 hands went up. That’s pathetic.

We also need more project-based learning out in the community so more people know what’s going on in our schools and want to support them when bond issues come around. The high school classroom is no longer only a physical place. At every high school within striking distance of the Connecticut River, for example, the science classes ought to be taking water samples, testing water samples, looking at current flow, counting the detritus flowing by and comparing notes. Another group of kids should be working on a video about the project that could be posted on YouTube. This means teaching not only an academic subject but also teaching a whole set of social skills about getting along with other people.

The great enemies of all this are cheap multiple-choice tests and a curriculum that requires you to study something that is a mile wide but only an inch deep.

What’s wrong with a wide approach?

Suppose a state official decides a high school student must read four plays in a month and write about each. That means teachers have no opportunity to work with students as they write and rewrite their papers. What’s to keep students from downloading papers and turning them in as their own work? They don’t even have to read the plays!

How can standards—and testing to measure progress—be improved?

We could have a healthy conversation about what we want our kids to be able to do and include a lot more people than just educators in that conversation. If wars are too important to be left to generals, education is too important to be left to educators. I think the president wants to have that conversation, and his [U.S.] Department of Education is enabling states to get together and talk about how to get higher standards and what those standards should be. No Child Left Behind (NCLB) set the process but left goals and standards to the states, which gamed the system. Now the education department is saying, “We will work out the standards and let you get there the way you choose.”

When it comes to testing, physicists, for example, could create 1,000 test items that cover all the different aspects of physics with a national test taken from those 1,000 items. Here are 12 questions on acceleration. Teachers then teach kids to solve and understand these 12 problems. If you put your best minds to work you could have good tests and teachers could legitimately teach to them. Meanwhile, schools should do benchmark testing every few weeks. They could use the data to say, “John needs more help with fractions,” and also cut across data: “None of the kids understands decimal points. Let’s figure out why.” That’s a rational system. That there is one test that occurs sometime in the spring—with everything riding on it—that’s insane.

You also have some strong feelings about grade grouping by age.

I think age segregation is silly and done only for the convenience of adults and the artificial, “What day in January were you born?” There is no reason that kindergarteners and first-graders and second-graders couldn’t be lumped together if you knew where everyone is supposed to be at the end of second grade.

What’s your take on the Obama administration’s “race to the top” approach?

It seems pretty clear they are going to redo NCLB and get rid of “adequate yearly progress” [the measure used to assess annual performance of a school based on the test scores of its students]. They’re talking about getting students either career- or college-ready, whatever that means. While they are closer to my own political philosophy than their predecessors, I still find it scary when anyone has all that power and dangles money out there in order to get charter schools, in order to get pay-for-performance for teachers—the reforms the Obama people believe are going to work. “Charter school” on the door tells you as much about the education offered as the word “restaurant” tells you about its food.

Is pay-for-performance a good strategy to retain good teachers?

It’s complicated. If a kid has a really great teacher for a few years in a row he will make all kinds of progress, and it’s clear who deserves credit. But who gets credit and who gets punished when you have kids constantly changing schools? I have met teachers who have 100 percent turnover of students during a school year. Paul Vallas, superintendent of the Recovery School District in New Orleans, swears by the Milken Foundation’s program, which pays teachers additional compensation for taking on leadership roles and helping their colleagues. He likes that it doesn’t base merit pay just on test scores. The old way—paying teachers based on years on the job and courses taken—is simply indefensible today.

How do schools find better teachers?

First the schools of education need to turn away more people. Teaching has to be a difficult profession to get into. Then it would have some prestige. A dean of one of the leading education schools once told me that half of the education schools should be abolished, and with few exceptions it doesn’t matter which half. They are just substandard.

How do you rate Teach for America (TFA)?

While there is a lot right with the program, there isn’t enough of a safety net for the teachers. There is in some TFA teachers an attitude of, “I’m here, everything is going to be fine now.” But teaching in really good schools is collaborative. If you come in with the attitude that “finally these kids have a teacher who cares,” it’s tough to get help from the veteran teachers when you need it.

What can Dartmouth do to improve secondary education beyond sending grads to TFA as it does each year?

Dartmouth students should graduate with some understanding of public education’s role in our democracy. Perhaps that would encourage them to become involved as citizens in improving schools in their communities, since only about 20 percent of households have school-age children. The institution of public education needs the support of a lot more people than just parents.

Meg Sommerfeld is a freelance writer. She lives in Rockville, Maryland.