Behind Enemy Lines

Lieutenant Richard Adam Kersting was a hero among heroes. A football player at Dartmouth, he enlisted in the Army in April 1942, joining the vast majority of his classmates to serve in WW II.

A combat engineer, Kersting and his unit landed on Omaha Beach in France on June 10, 1944—just after D-Day—and supported infantry troops fighting to liberate the strategic town of Saint-Lô. His incredible story was chronicled by The Philadelphia Inquirer on July 23, 1944.

He told a reporter that he had not expected much action but was prepared, thanks to his Army and football training. He had received Ranger training and played blocking halfback under coach Earl “Red” Blaik at Dartmouth.

“Coach Blaik taught us to think while in motion, to never leave an opening for the opponent, to keep an eye on the ball, and to cash in on the other guy’s mistakes,” he said. “With two-and-one-half years of Army training on top of that, plus an awful lot of good luck, we got by.”

The day the article ran, Kersting’s mother heard an interview with her son on Army Hour, a national radio show. The following is a condensed version of the Inquirer story that ran 75 years ago (the full account can be found in DAM’s archives).

“Dummkopf!” Kersting shouted and booted the hapless man’s backside.

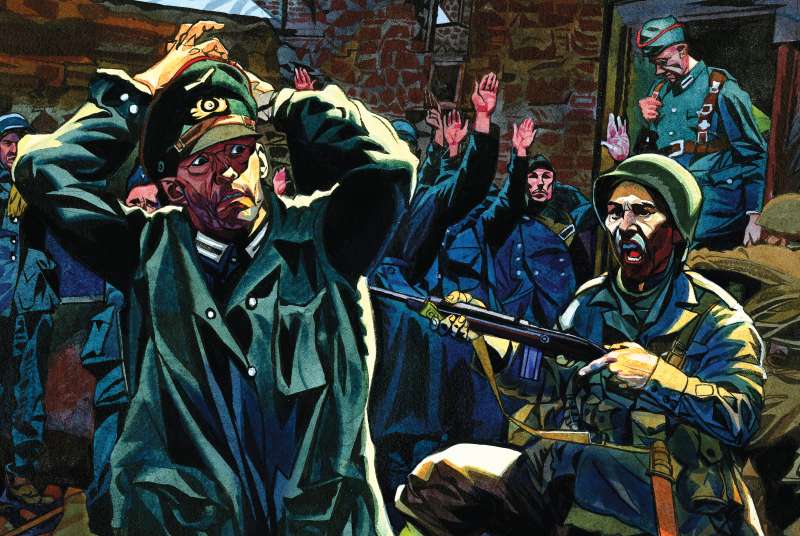

At about 4 o’clock on the after-noon of July 11, near the broken Normandy village of Cavigny during an American southward drive to Saint-Lô, two combat engineers appeared at a medical aid station with 34 Nazi soldier prisoners between them.

Nine more lay dead in the wrecked houses and the rubble-covered streets behind them. The German platoon headquarters, a virtual fortress, was wrecked.

The senior Nazi officer, an ober lieutenant, turned to one of his captors and in good English said, “You’re mighty lucky to get away with this, you so-and-so,” and proceeded to curse him.

For a reply, Lt. Richard Kersting of Oxford, Ohio, fetched the arrogant Hitlerite a swift kick in the seat of his breeches, a fitting conclusion to one of the most dramatic incidents of the war thus far in France.

It had started as a routine mission for Kersting and his rifleman, Pfc. Max Nimphie. They left their cargo-carrier and, under fire from Germans, reconnoitered on foot along the highway where a German platoon hidden in the hedgerows was holding up the advance of tanks and an American infantry regiment.

The two moved south along the road, drawing occasional rifle fire as they walked. The crew of an American tank nicknamed “Foudroyer” hailed them with the warning that a German tank was around the corner. At the same moment it fired on them. Kersting dashed across the road and circled behind the hedgerow toward the enemy.

He and Nimphie fired into the tank’s gun ports, forcing its crew to shut them. When an American bazooka squad appeared, Kersting ordered them to flank the tank. The bazooka boys put four rockets into the turret, blowing it apart.

Continuing along with Foudroyer covering them, Kersting saw something that enraged him. An American corpsman wearing a Red Cross armband lay dead by the roadside, two bullet holes in his back.

“That made me mad,” said Kersting. “I don’t mind the enemy shooting at me in a fair fight, but they don’t play fair. They tried to interfere with our way of thinking. They’ve ruined the minds of a whole generation of Europe. They’ve dragged us into this dirty war—you, me, all of us Americans who don’t give a damn about soldiering and would rather play ball any day—and now, goddamn it, they’re going to pay.”

A German came out of the hedgerow, hands high. “I worked him over a little and got him to tell the whereabouts of others,” Kersting said. The prisoner quickly surrendered, pointing to houses farther along where his comrades had holed up.

Kersting and Nimphie continued into the enemy’s stronghold while the bazooka team took the German and two other prisoners away. From time to time the pair tossed a grenade into a house or shot a fleeing German.

“I yelled ‘Ergebt euch!’ which means ‘Give up!’ They were running like hell, crossing the road toward two big buildings,” said Kersting, who called for 75-mm fire from Foudroyer.

As shells burst inside the first structure, it crumbled like a cakebox, and the enemy inside sped for the second building. “We were making plenty of noise,” said Kersting. “The tank’s clatter must have convinced them we were a whole regiment.

“Just then somebody turned the corner with a submachine gun in his hands. It was a German, and his mouth flew open when he saw me. The weapon was pointing directly at me, but I beat him on the trigger. It was Wild West stuff, only I didn’t think of it then. My mind was going like a flywheel. It was like grabbing a fumbled ball in midair, seeing a hole, and streaking for a touchdown. Then I strode to the door, gave it a hell of a kick, yelling loudly, carbine pointing in, and stepped back. All I could see was faces, and they were white as paper. Those Heinies were scared stiff.

“It was a situation demanding boldness. When the first guy stepped forward, his machine gun stuck into my belly. I brushed it aside and didn’t shoot him. Something told me if I killed him they’d all begin shooting from inside and finish my run of luck, so I threw his gun aside and shouted ‘Hände hoch!’ [Hands up!] and they started out the door.”

The second man through the doorway was the ober lieutenant. Kersting demanded to know why he had not surrendered when it was obvious the Huns were surrounded.

“Dummkopf!” Kersting shouted and booted the hapless man’s backside.

Three days after his mother heard him on the radio, Kersting died when he stepped on a mine.

One after another, 30 soldiers filed out, hands high. Each dropped a rifle, grenades, a machine pistol, or a gun at his captors’ feet. As the last obeyed the order to come out, Kersting saw a rifle muzzle, and a shot just missed him. He sprang forward and returned two shots. When soldiers revisited the place the next day, they found the dead sniper in the burning house with other dead Nazis.

The ober lieutenant became suspicious and demanded to know where the rest of the American brigade was. But the Nazis had no weapons, and Kersting and Nimphie were in no mood to debate the issue.

The next day Kersting learned why no other Americans were nearby. Along the same road he found five American tanks smashed by enemy fire and the bodies of their crews. “I had only been in France a few days, and this had been my first combat experience, and then I saw something that made me cold inside,” said Kersting. “It was Foudroyer, the tank that had covered us. I looked inside. The crew was still there. Damn the Germans. I hope we don’t let them up until we settle all these scores, and you can put it in the paper that that is how all our fellows up front feel.”

Three days after his mother heard him on the radio, Kersting died when he stepped on a mine during a night mission. He was 22. He was awarded a Purple Heart and the Distinguished Service Cross.

Theodore L. Bracken ’65 visited the graves of these five alums at the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial at Colleville-sur-Mer, France, in 2016. His research led to this article. He can be reached at ted.bracken@yahoo.com.

Band of Brothers

Four more alums were awarded the Purple Heart for their deeds in Normandy 75 years ago.

First Class Seaman Fletcher P. Burton Jr. ’45

U.S. Coast Guard

“Fletch” Burton hit Omaha Beach early—in the second wave of attackers. He manned the pilothouse of landing craft 94, controlling its throttle. Artillery shells burst around his unwieldy vessel as it surged forward, dodging obstacles before it plowed into the sand. After its troops plunged ashore, the 94 struggled to free itself. At the same time, famed war photographer Robert Capa waded out, requesting permission to come aboard. At that moment at least one artillery shell found the landing craft. Shock from the blast killed Burton. Capa’s picture of Burton’s injured crewmates appeared in Life magazine. Burton had left Dartmouth during his sophomore year to enlist. He previously made combat landings in North Africa, Sicily, and Salerno, Italy. As one of the first to die on D-Day, his name appears on the “First Fallen” plaque at the Pentagon that honors the first 30 men who were killed that day. He was 21.

Second Lt. Edward Titus Jenkins III ’37

U.S. Army

“Anything, Anytime, Anywhere—Bar—Nothing.” That was the motto of Jenkins’ outfit, the 39th Infantry Regiment, the Fighting Falcons. He enlisted in January 1941, rose to second lieutenant, and became an anti-tank officer. After landing on Utah Beach on June 10, Jenkins headed north to liberate Cherbourg, a major deep-water port near the tip of France’s Cotentin Peninsula. Then his regiment pivoted south to attack Saint-Lô, a fortified town at a strategic crossroads. Jenkins, 28, died on July 11 near Carentan, 18 miles north of the city. A native of Queens, New York, he was on the swim team and went to Tuck his senior year. Jenkins was also awarded a Bronze Star and a Divisional Citation.

Staff Sgt. James Ambrose O’Hearn Jr. ’41

U.S. Army

O’Hearn had a great sense of humor. “The Army took me in tow in May 1942,” he wrote his class secretary in April 1944, “and before the leaves fell that year I was given a free ocean trip over here to England.” He joked in his letter that he earned his European Theater of Operations ribbon for courageously confronting Spam in the mess hall. A staff sergeant in an anti-tank unit, O’Hearn dodged machine gun fire when he landed on the unsecured Omaha Beach the day after D-Day. His unit immediately marched inland. When it attacked the next night, the Germans counterattacked with artillery. He died in the barrage. O’Hearn, 24, was engaged to be married and was from South Orange, New Jersey.

Pfc. James Robert Whitcomb ’38

U.S. Army

In early 1941, Whitcomb saw the war coming and wanted to serve as a pilot. But the Army wouldn’t let him fly because he wore glasses. Whitcomb landed on Omaha Beach 30 days after D-Day. His regiment took heavy casualties as it fought in thick hedgerows on the way to Saint-Lô. He never saw the city, dying in a firefight on July 28. Whitcomb, 27, called Portland, Maine, home and was on the swim team. He left behind a wife and a son.