The River Master

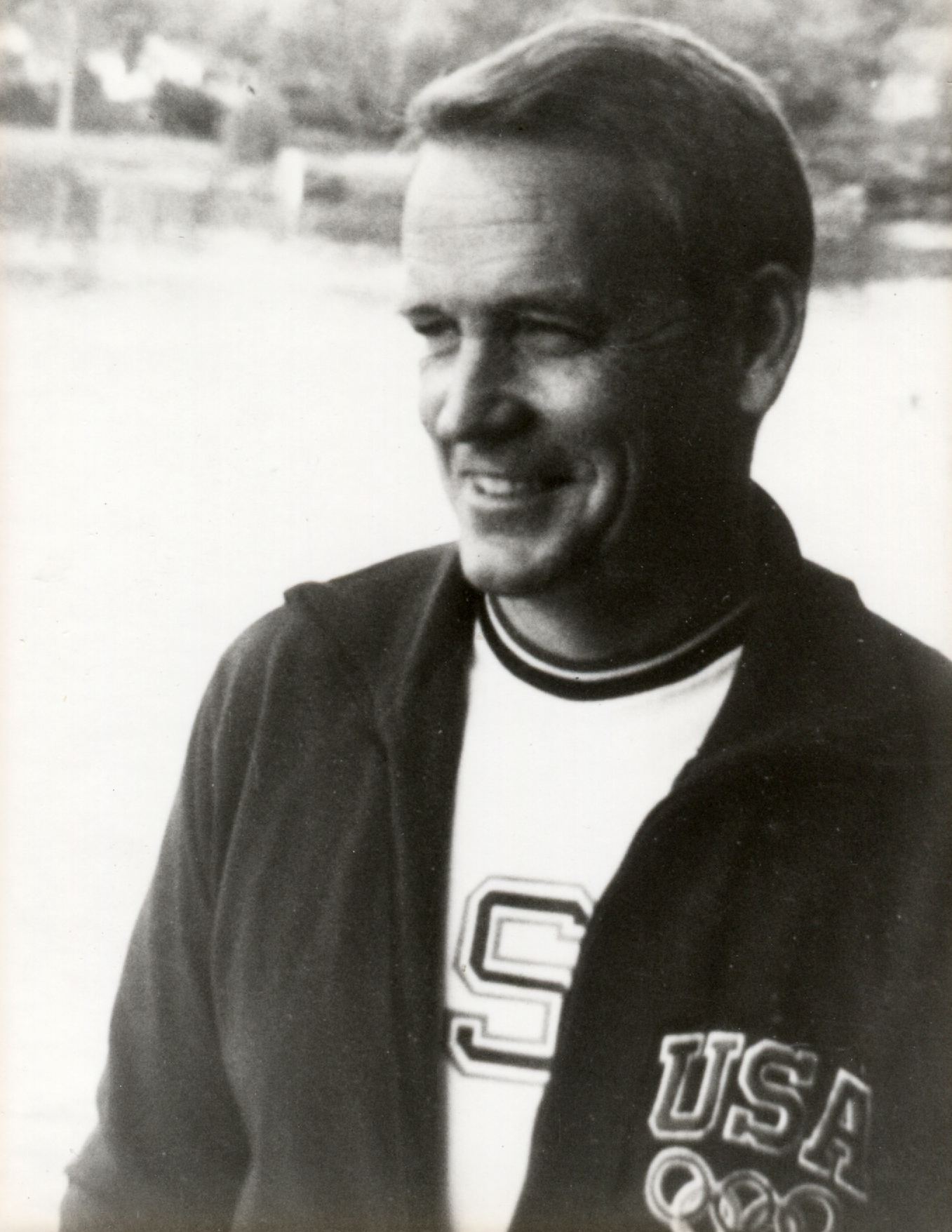

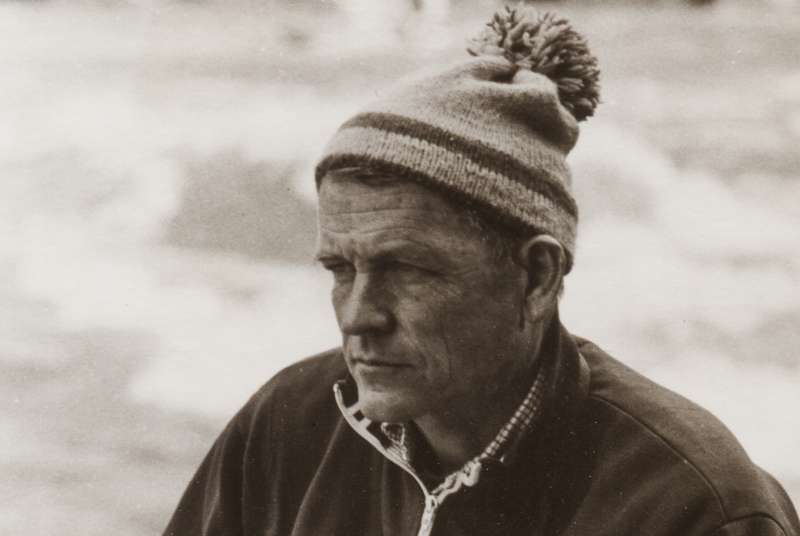

In his quiet, confident way, Jay Evans (1925-2018) made waves coaching Ledyard Canoe Club paddlers and U.S. Olympians. The sport of whitewater canoeing and kayaking lost a visionary leader and stellar mentor when he died last April at the age of 92.

Evans served from 1962 to 1974 as the club’s advisor, and, by coincidence, his passing occurred during its annual Riverfest weekend. At Dartmouth Evans coached Ledyard paddlers to national championships in men’s kayak and men’s single canoe, and his current or former Dartmouth students represented the United States at every world championship from 1965 to 1973 and at the 1972 summer Olympics as well.

He was best known, however, as the first coach appointed to the U.S. whitewater team at the world championships in 1969 and 1971. He then coached the first U.S. team to appear in the Olympics in 1972. Under his leadership America won its first medal—a bronze—in international whitewater competition. Evans also wrote three of the first books published in the United States on whitewater kayaking

“To paddlers whose lives he shaped and to the sport whose horizons he expanded, Jay was much more than a coach,” says Wick Walker ’68. Evans’ son, Eric, whom he coached at Dartmouth, and six other former athletes share these memories of him.

Dad and Dan Dimancescu ’64 hunched over the kitchen table at our house by Hanover’s First Reservoir. They were exploring Dan’s idea of a Ledyard canoe trip down the 1,650-mile length of the Danube River that would take place in 1964. I was about 12 at the time and saw nothing impossible about a plan to paddle across and then behind the Iron Curtain during the depths of the Cold War or to obtain the support of National Geographic to do so. Neither did Dad. That was the whole point of this unprecedented outreach across the divide. That was what would make the adventure special.

A people person, Dad encouraged “characters” to pursue their dreams, frequently with astonishing results. That 1964 trip became a cover story in National Geographic magazine and launched more than one photography career. —Eric Evans ’72

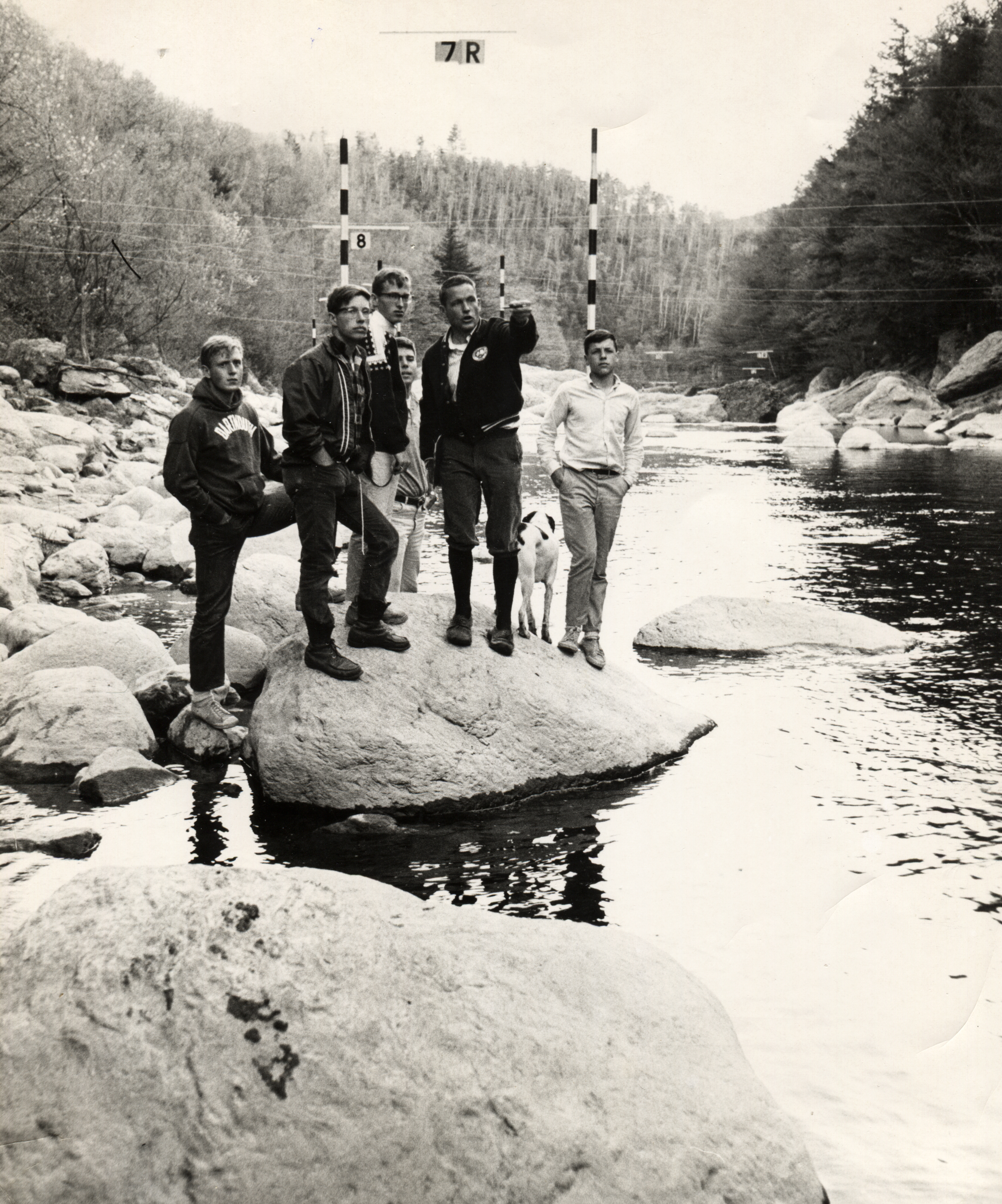

The site is the West River in Jamaica, Vermont. The date, late spring 1965. The event, a whitewater slalom race. The river is not up yet. Some racers scoping out the course are led by a dapper fellow in knickers and a club jacket. Soon the dam upstream will open, the water will rise, the rocks will be covered by swirling water, and the race will begin.

My memories of that spring day are vivid. Some of its main participants were captured in a photo. Its central figure is Jay, seen pointing, the club’s advisor. His son, Eric (at far right), was still in high school and starting a racing career that led him to nine straight national kayak slalom championships. To Jay’s right is the barely visible Al McKibben, Tu’65, one of many members of the Dartmouth community who Jay drew to Ledyard through the lure of whitewater racing.

Jo Knight ’67, DMS’69, is in front of McKibben. Knight’s father’s and brothers’ love of canoeing and the outdoors had contributed to a revival of Ledyard a few years earlier. In summer 1964 his family paddled the intracoastal waterway north of Seattle in mahogany double kayaks. His brother, Pete ’62, and Ben Drew ’59, Tu’60, had earlier spent a summer circumnavigating New England in an open canoe.

Wick Walker stands in front of a pole. Though he was a freshman, he was experienced in one- and two-man whitewater canoes and brought the team a familiarity with whitewater that made the most difficult drops seem achievable. His racing skills were superb. He could slip his canoe through tight slalom gates with grace. Walker and Knight both made the national whitewater slalom team that summer.

The person with one foot on the boulder (at far left) is me, wondering what exactly is about to happen. Who are these intent and nimble people scampering about the riverbed, pointing out water features that might appear in the future? It is my first spring on the whitewater team, and I am not too sure of anything, except that I’d like more of this. —Sandy Campbell ’67, DMS’77

The West River race was over, and the water level had returned to a trickle late that afternoon in spring 1965. I had paddled as well as I could have expected, but more seasoned paddlers took the medals. It was painfully clear I needed more experience and to sharpen my skills.

After an organizers’ meeting, Jay appeared and took me aside, his face intense, excitement in his voice. A slot on the U.S. team going to the World Championships in Austria that summer had suddenly opened up. He had put forward my name. He wanted to know if I would go. I was flabbergasted. Without Jay’s boundless enthusiasm and totally unwarranted faith that I could do it, I would never have attempted racing at that level. Intense learning experiences are often compared to “drinking from a firehose.” That summer I learned by literally drinking from the flooded Lieser River. But learn I did.

I repeated that pattern many times, as did many others. Jay was more than a coach. For me, he was an “enabler.” Shortly after the Olympics I shared with him my vision of paddling expeditions in the Himalayas. I told him I had my doubts. The whitewater would be scary, and the logistics of organizing such a thing halfway around the world was equally daunting. Jay’s quiet message was: This goal is worthy of great effort, and you are exactly the right person to accomplish it. Encouraged, I trained for three years in the Alps with the Alpiner Kanu Club and then went to Bhutan in 1981. It was the start of a lifetime of international exploration. —Wick Walker ’68

The first two people I met at Dartmouth in September 1965 turned out to be two of the most influential people in my life. Jay Evans and Wick Walker were manning the Ledyard booth on activities night. They were recruiting green freshmen (in my case a very green 18-year-old newcomer) into the birthing of the Ledyard juggernaut.

Jay was the best mentor I could have asked for. He was disciplined, focused, competitive, and creative. We never stopped working on technique and conditioning, all while maintaining an optimistic, positive attitude. Jay taught us to welcome adversity, something easy to find in spring conditions in northern New Hampshire. If the snow was blowing sideways, we always knew we had an advantage over those unaccustomed to such challenges.

After Jay coached the U.S. teams in the 1969 and 1971 World Championships, I tried to partially fill his shoes at the 1973 World Championships in Switzerland as one of the team’s three coaches, an experience that foreshadowed the end of my brief banking career, which began in 1971 when I moved to Philadelphia to train for the Olympics.

Our first training camp for the championships was hosted by the Nantahala Outdoor Center (NOC), a visionary outdoor enterprise in North Carolina that had been founded the year before. Molded by Jay’s idealism, his embrace of lofty goals, and his example of behind-the-scenes service to the sport, I continued my river journey in 1975 when I left banking and went to work at the NOC. Jay could not have been prouder.

Since then, I’ve been privileged to participate in the NOC’s growth. It has gone from annually guiding a few hundred rafters down the Nantahala and Chattooga rivers and offering several kayak and canoe classes to becoming one of the world’s premier outdoor adventure providers. Now, 45 years later, it provides about 700 outdoors-related summer jobs, takes 108,000 rafters down eight southeastern rivers every year, and trains hundreds of paddlers from beginners to Olympians and swift-water rescue professionals. The NOC’s staff and customers are led to places of courage and accomplishment they didn’t know they could find in themselves. Jay would have expected nothing less. —John Burton ’69

Jay helped guide me out of the regimented, richly financed world of Harvard crew into the free-form, make-it-yourself, little-financed world of whitewater canoeing and kayaking in the 1960s. It’s strange to think now how taking that road less traveled was just the beginning of my experience with international sports in 72 countries across five decades.

Jay was always involved in the outdoors, be it skiing, mountaineering, camping, or Outward Bound instructing, and this included whitewater canoeing in open Grummans in the late 1950s, when he taught school in Virginia. He transitioned to kayaks in the early 1960s in Massachusetts, where he learned the Eskimo roll by himself in a neighbor’s swimming pool. Starting in 1962, when he took a job at Dartmouth, Jay started competing on the eastern whitewater circuit in homemade fiberglass kayaks with cloth decks.

On the East Coast in the late 1950s and 1960s, two groups dominated slalom racing in canoes and kayaks: youthful competitors from the Boy Scouts and outing clubs (most notably Penn State’s) and white-collar professionals, many of whom were from Washington, D.C., and New York City and had alpine skiing backgrounds. All were essentially weekend warriors. They would head to a river on a weekend, camp, hang a few gates the next day, run a slalom, and then run the rest of the river in the boats they had raced in.

“What you do as part-time recreation, in Europe is a full-time sport,” said Paul Bruhin, a member of Switzerland’s 1963 slalom and wild-water teams. Back then the idea of daily mid-week training sessions was only beginning to cross the Atlantic. Jay picked up on this early, and when he got to Ledyard, he and his paddlers became athletes first. The camping experience became secondary, almost irrelevant. Thanks to Jay’s leadership, American kayakers and canoeists in whitewater racing became athletes during the years he coached the Ledyard and U.S. teams. —Bill Endicott

My husband, Bill, and Brad Hagger competed in the two-man whitewater canoe and narrowly missed being selected to the 1972 Olympic team. I thought our Olympic dream had died.

Jay had previously recruited me to assist him in Augsburg, Germany, near Munich, where the competitions were to be held. Now he took a further step. He persuaded Bill to come as his assistant coach. This Olympic experience marked the beginning of our awareness that Bill might make a far greater contribution as a coach than as an athlete.

Without Jay’s quiet, confidence-inspiring nudge that was so typical of him, Bill might never have stepped into his mentor’s shoes. Under his leadership, the U.S. team dominated world rankings, thanks to one-man whitewater canoe competitors Jon Lugbill and Davey Hearn, and the team won its first gold medals in world championships and gold and bronze medals in Olympic slalom. Bill also authored several books on the sport, founded the Slalom World Cup, and advised developing slalom programs in Europe, Australia, Chile, and China.

Jay continued to shape my life as well. The American Canoe Association realized that its members, who already excelled as athletes and coaches, needed to serve on international governing committees as well. With Bill’s Olympic experience and Jay’s trust, I had the confidence to accept appointment as the U.S. representative on the International Canoe Federation’s promotion and information committee. Capitalizing on that experience, I later joined in efforts to get slalom reinstated in the Olympics in 1992 after a 20-year hiatus. —Abbie Endicott

When Scott Strausbaugh and I won America’s first Olympic slalom gold medal in Barcelona, Spain, in 1992 we had never met Jay. Yet we knew his name and felt his influence through our coach, Bill Endicott, and teammate Jamie McEwan.

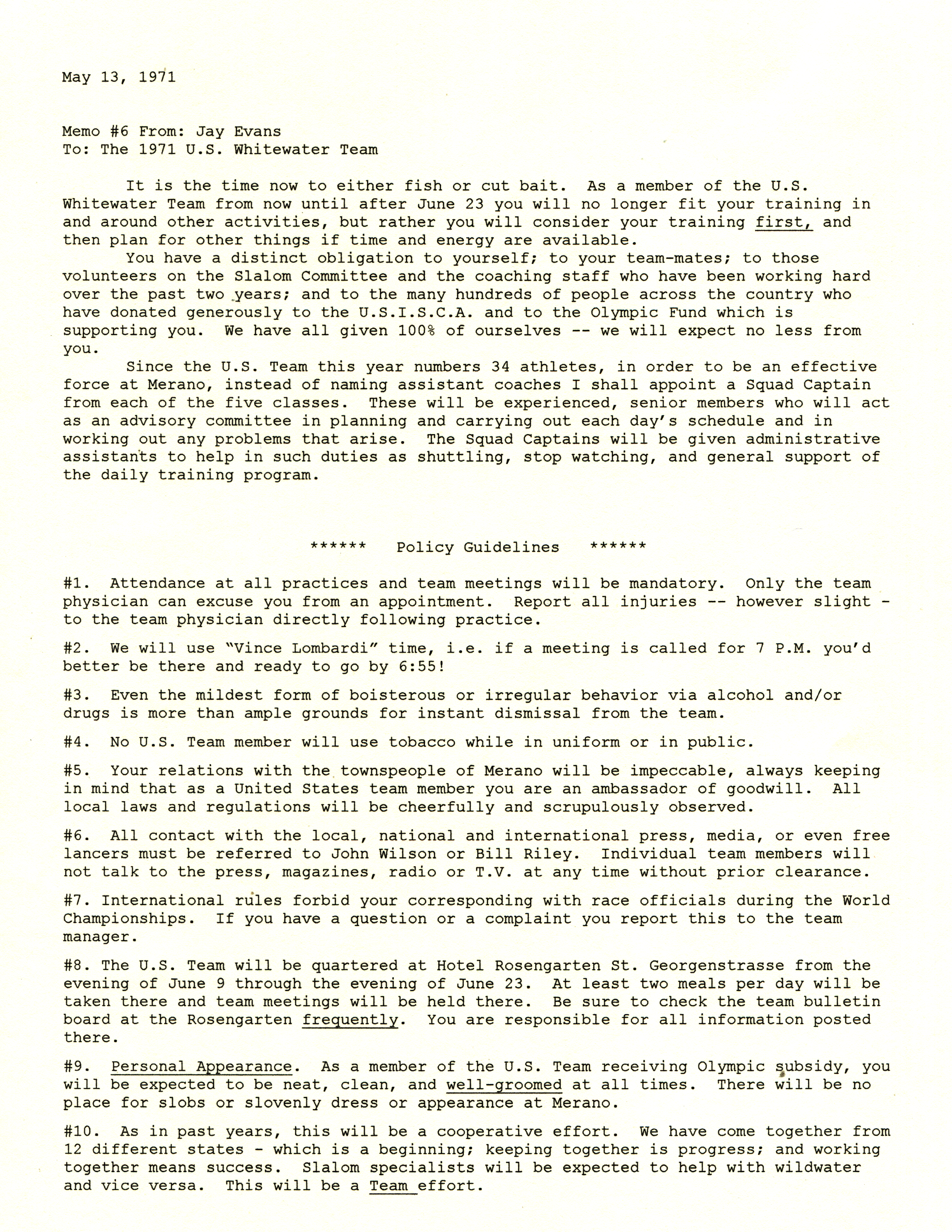

Wick Walker, who paddled for Jay at Dartmouth in the 1960s, recently showed me a memo Jay sent the U.S. team in 1971 when he was forging whitewater racing’s future. Wick asked me what I thought of it. I told him Jay’s memo outlined more than rules for Team USA athletes. It was a guide to help us become the men who would serve the U.S. program in ways we could not have foreseen. My only suggestion to Wick was that we consider striking a line through the memo’s date, “May 13, 1971,” and next to it write the word, “Timeless.” —Joe Jacobi