In the midst of the Civil Rights Movement and Black Power Movement, Dartmouth students, officials, and alumni waged a tenacious, relatively successful campaign to increase black admissions to the college, a fight that was also rooted in larger national developments.

In the midst of the Civil Rights Movement and Black Power Movement, Dartmouth students, officials, and alumni waged a tenacious, relatively successful campaign to increase black admissions to the college, a fight that was also rooted in larger national developments.

Dartmouth did not experience the highly dramatic rebellions that its peer institutions witnessed. Unlike Cornell, there were no black student activists parading with rifles to defend themselves at Dartmouth. Dartmouth students did not attempt to take a dean hostage, as some had at Columbia. They did not invite world-renowned black militants onto campus to join their demonstrations, as some did at Yale, nor did they walk off campus in a boycott, as did young learners at Brown.

Black students at Dartmouth acted on their own behalf and were able to alter the traditional policies of higher education while advancing the black freedom movement on-and-off campus via small but effective campaigns. Students and officials took advantage of the activism elsewhere to advance their causes on campus.

Dartmouth avoided much of the era’s tumult and turmoil by both acceding to the demands of its black students and taking proactive steps toward improving race relations. It made an institutional effort to become a place where black students felt welcomed. Dartmouth officials learned from what happened elsewhere and thus escaped the more dramatic showdowns that rocked other campuses. By the early 1970s, Dartmouth had a Black Studies program, a black culture center and residence hall, an admissions strategy to recruit and matriculate a higher number of black students, and seasonal and year-round programs that assisted urban black youth who hoped to attend college.

What happened at Dartmouth highlights how a movement that originated with a push to empower the poorest and most disenfranchised members of black America found its way to one of the most exclusive spaces in the country, an Ivy League college. Those black students who could and did attend Dartmouth were usually their communities’ elite, yet they chose to propagate a campaign that intended to bring freedom to the black masses. Indeed, by the 1960s, Black Power had invaded the Big Green.

Black Students Provided the Vigor

“The fraternities are violating the civil rights of every Dartmouth man.”

There is almost no black community in the Upper Valley region of New Hampshire to influence policy making at the governmental or college level. In this racially homogeneous space, black students at Dartmouth acted by themselves as the key catalysts for change. This set them apart from many of their protesting peers in the Ivy League and around the nation who were closer to support networks.

Although universities looked to public and urban secondary schools in the late 1960s to achieve racial diversity in higher education, Dartmouth took that effort to another level. Dartmouth not only recruited middle-class black students from elite college preparatory schools, but the College also recruited self-identified members of a notorious youth gang on the streets of Chicago. This, along with the eventual arrival of black women, faculty, and staff on campus greatly added to the diversity of the student body and partially relieved black students’ sense of otherness.

Under the leadership of President John Sloan Dickey ’29 from 1945 to 1970, Dartmouth had no internationally famous student strikes or demonstrations, yet it achieved many of the same goals that activists fought for at peer institutions.

Dickey had been one of 15 luminaries who served on President Truman’s prestigious Committee on Civil Rights. After learning in great detail about the issues that challenged black America on a national level, Dickey and his administration attempted to bring civil rights to his own institution by helping to significantly increase the population of black students. His hope (and that of black people throughout the country) was for education to lead to racial equality.

Like many northern institutions and most Ivy League universities, the College did not overtly discriminate on the basis of race. In fact, its policies suggested some respect for the black freedom struggle. Not only did it admit black students, but in 1954 Dartmouth passed a referendum outlawing several other forms of discrimination in the Greek system: “By April 1, 1960, any fraternity, which as a result of a nationally imposed written or unwritten discrimination clause restricts, or can be interpreted to restrict membership because of race, religion, or national origin, shall be barred from all interfraternity participation.”

Although most northern universities celebrated the idea that they, unlike their southern counterparts, admitted black students, once those students arrived they were not welcomed by certain segments of these institutions. After the denial of a black student by Sigma Epsilon Chi in 1963, the school’s Interfraternity Council pledged to make every attempt to “eliminate discrimination at Dartmouth.”

Students weighed in on the fraternity’s and Dartmouth’s actions. Terry Lee ’65 wrote to The Dartmouth, saying “I think that to alter fraternity procedure enough to prevent discrimination on racial and religious grounds” would mean that the “right of private association would be abrogated.”

David Johnston ’66 countered that the fraternities on campus were not private and that they were a part of the larger college. He explained that “If those fraternities could exist as separate entities, without affecting anyone else with their personal prejudices, I would say fine. . . . [B]y discriminating against a person because of his ascribed status, the fraternities are violating the civil rights of every Dartmouth man.”

The debate about fraternity admissions on campus mirrored the one concerning civil rights in larger American life. In other arenas, it took sit-ins and boycotts to change policy; at Dartmouth, change happened much less dramatically but no less significantly.

Taking a Chance on Gang Members

“I Know I Can Do Just as Well.”

During the late 1960s, Dartmouth admitted more black students than ever. To encourage such enrollments, Dartmouth looked for promising candidates from poorer neighborhoods. While many earlier students had come from the black middle class and more exclusive high schools like Brooklyn Tech and Stuyvesant, Dartmouth, as did its peer institutions, the College broadened its search to include less prestigious public schools.

To assist in the search, Dartmouth employed the use of several programs, including the National Scholarship Service and Fund for Negro Students, Outward Bound, an exchange program with Alabama’s historically black Talladega College, and a program started on Dartmouth’s campus to create a pipeline for future black students.

The College’s isolation, in contrast to its peer competitors, forced its officials to be more intentional and work harder to recruit black students. To cultivate potential students, Dartmouth authorized the establishment of its “A Better Chance” program in 1963. Dartmouth, along with 20 preparatory schools in the Northeast, launched the project to groom high school students.

With help from the Black Alumni Association, Dartmouth later established the Foundation Years project, which was a transitional program for young black men. In an effort to address the inadequate schooling and preparation that many urban black people suffered, Foundation Years offered students the opportunity to work their way up to college-level courses. Those who finished the two-year program and were able to pass the College’s entrance requirements could enroll immediately at Dartmouth.

Edward “Pepilow” Marlon Perry, the founder of the Chicago street gang Conservative Vice Lords, spent time with David Dawley ’63, a white Dartmouth alumnus who participated in a two-year embedded study with the gang. Afterwards, he took advantage of the Foundation Years program.

When asked about the prospects of succeeding in college life, Perry explained that white people “taught me to believe I was second-rate. I believed it for a long time, but I don’t now.” His indictment of white people must have excluded Dawley, who became a friend. “My two friends from the Lords . . . went up there, and they were just dynamite. . . .I know I can do just as well,” Perry predicted.

Coming from Lawndale, a predominantly black and impoverished neighborhood in Chicago, Perry wanted better for himself and his family. “I want that degree. I’ve seen what it can get,” he said. Perry was one of 18 black students who participated in Foundation Years. Of those 18, all but one came from Chicago.

In an effort to assist the community that they claimed President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society had failed to help, the Conservative Vice Lords even provided financial assistance to local students who left the city to attend Dartmouth.

The Foundation Years and A Better Chance programs set the college apart from many of its peers and showed what was possible when institutional commitment met the individual desire for advancement. By inviting members of a youth organization with a reputation for violence, Dartmouth risked its reputation of exclusivity and isolation, not to mention the possibility of campus unrest.

Surely college officials had doubts, but they took the mission to heart by offering opportunities to young people who would be ignored by most programs. In this way, Dartmouth positively influenced the life chances of individual African Americans as well as the larger black freedom movement.

Confronting the Power

“The administration always needs more facts.”

With the advent of Black Power, there were changes in the demeanor of Dartmouth’s African American students. Black students in the latter part of the decade found themselves more likely to physically or verbally confront their white counterparts than those who came before. Dartmouth officials, like those at peer institutions, needed to accommodate this new age of students.

Rather than trying to fit in and integrate, many in this new group of black students sought to establish new identities by creating the Afro-American Society (AAS) in 1966. The 45 members of Dartmouth’s AAS wanted to “be assimilated into those things of our choice, without loss of the things important in the heritage of the American Negro,” stated AAS president Woody Lee ’68. Although he had been reared in a suburban New Jersey town, Lee asserted his black identity more than ever at Dartmouth, as he desired to join the movement. Dartmouth accepted and funded its black students’ manifestation of the movement by recognizing the AAS.

The AAS was similar to peer organizations at other Ivy League schools, and it worked tentatively with the campus’s chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a national New Left organization created in 1960 whose Dartmouth chapter emerged in 1966. In the late 1960s, SDS protested on campuses across the nation to end the war in Vietnam, fight racism, increase opportunities for the poor, and achieve power for young people.

SDS members teamed up with AAS members to demonstrate against Dartmouth’s $400,000 investment in Eastman Kodak. Dartmouth students decided to act in April 1967 after discovering that the Kodak plant in Rochester, New York, refused to hire black employees. They joined ranks to support the Rochester black advocacy group Freedom Integration God Honor Today (FIGHT), which was partly inspired by radical white organizer Saul Alinsky. Dartmouth student activists brought college officials a demand to remove the college proxy from the Kodak board, in addition to appealing to the company itself.

The treasurer and vice president of Dartmouth, John F. Meck ’33, upon meeting with representatives of the AAS, SDS, and the Dartmouth Christian Union, first suggested that Kodak had good leadership and that the company was capable of making fair decisions with respect to hiring.

Then, in predictable institutional fashion, the vice president suggested that a campus committee be formed to study the college’s investment policies.

The students were wary of such tactics. “I’m highly doubtful of how effective it [a committee to study investment policy] will be,” stated AAS leader Woody Lee. Using the rhetoric of the Civil Rights Movement, he continued, “We have to face the issue—the students can’t wait for the administration to do anything.” An SDS leader concurred, observing, “the administration always needs more facts.”

Confronting what students for decades had battled, the activists met with entrenched university bureaucracy. To overcome it, they forced the issue by occupying the office of President Dickey, while allowing business to continue. Dartmouth students did not grind university operations to a halt as militant students did at peer institutions like Princeton. The brief demonstration at Dartmouth ended a few hours after it had begun, but the students had proved their point and acted on behalf of the black community. Their efforts marked the variance in the methods of Black Power.

Although the college never removed its proxy from the Kodak board, the company subsequently hired black workers. In this instance, black students in collaboration with their white allies at one of the most elite institutions in the nation went beyond campus to advocate the progress of the black working class. This was a significant alliance that resulted in a small victory for the larger freedom struggle.

Big Changes Between 1963 and 1967

“We will have to repent in this generation…”

Around the same time, Dartmouth faced other race-based controversies. Like many universities across the nation, Dartmouth sometimes hosted notorious and divisive figures. Two speakers who caused student uproars were Alabama Governor George Wallace and racial theorist William Shockley.

Wallace’s home state was at the forefront of the civil rights struggle. With school-aged youth and older activists like Fred Shuttlesworth and Martin Luther King Jr., leading the fight to end segregation, Wallace and Birmingham Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene “Bull” Connor used their authority to maintain the “southern way of life.” The world watched as Birmingham city authorities assaulted black American citizens who demonstrated for their rights.

By the time of Wallace’s first visit to Dartmouth in November 1963, he had observed the deaths of four black girls who were killed in a church bombing in Birmingham, closed public schools to prevent desegregation, allowed “Bull” Connor to mobilize the fire and police departments against peaceful youth activists during the Children’s Crusade, and stood in the doorway of a University of Alabama building to intercept enrolling black students.

When he arrived at Dartmouth, students and faculty met him with varying reactions. One group of students, which included people who had participated in the Civil Rights Movement in the South, planned interracial pro-integration marches before and after the speech.

Though a number of Dartmouth students supported the idea of picketing Wallace, one thought the idea was immature and departed from the local culture by encouraging students to close their minds to new ideas.

Another astutely brought up the irony of students on Dartmouth’s campus wanting to picket the southern segregationist but not taking the same measures to attack northern segregationists, like segregated fraternities—on campus!

A student from Alabama praised the work Wallace had done with regard to internal improvements for the state and decried the reaction of Northerners. A second Alabaman believed that black people in his home state should have the right to vote—eventually. He stated that black people are “easily corruptible . . . and prone to not use their votes wisely.”

Although Dartmouth appeared to support the Civil Rights Movement, Dartmouth students still had to confront segregationist sympathizers on their own campus. Campus groups like the Political Action Committee and the Dartmouth Christian Union attempted to counter segregationist ideology by donating money to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and by traveling to Mississippi to work with the organization.

Members of the faculty arranged for Wallace’s arrival. A contingent of professors planned to demonstrate their disapproval of Wallace’s views by donning black armbands and protesting silently, a method that organizations such as labor unions and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had used for decades.

Like those who attended the monumental March on Washington earlier in the year, almost 20 faculty members and hundreds of students, most of whom were white, marched through campus and around the field house, singing “We Shall Overcome” and carrying “Freedom Now” signs.

On the day of the event, the school newspaper reported that there had been might have been more applause than jeers for the governor.

A spokesman for Wallace said he believed that Dartmouth students were better representatives of an educational institution than those at Harvard, whose interruptions had prevented him from carrying forth with his speech the day before.

One Dartmouth student speculated that there would have been more disruptions than cheers, but that students had decided to remain respectfully silent. Martin Luther King Jr. argued in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail, “We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people.” If the men who left Dartmouth went on to become world leaders, they would have to take a stand on the issues that affected their own nations and institutions. They would not always be able to remain “respectfully silent.”

Wallace visited Dartmouth again in May 1967, campaigning as a presidential candidate, at the invitation of The Dartmouth, he found that much had changed. The approaches to the movement for black freedom began to shift from boycotts, sit-ins, and marches to more militant tactics and rhetoric. He met a student body with a new and more militant attitude. Whereas before students and faculty members had met Wallace with a march and silent protest that mirrored some of the civil disobedience methods in practice at the time, The Dartmouth reported that students in 1967, some from the AAS, jeered during the speech and led a walkout.

The Black Judiciary Committee

No one chose to identify himself.

Then, in one of the most militant acts of the decade, some students, including members of the AAS, attempted to turn over the former governor’s car and banged on the top of the vehicle as he left campus following the speech. By interrupting Wallace and disrupting his exit, the students violated one of the college’s most sacred ideals: academic freedom. Although college officials were sympathetic to the AAS’s position regarding Wallace, they felt that in advancing its own ideas, the AAS had impeded the rights of others to hear different viewpoints.

Embarrassed by the students’ behavior, the administration sent a letter of apology to Wallace. In response to the demonstrations, the administration condemned the black and white student participants and brought many before the judiciary board. Eventually, Dartmouth called for the suspension of those students who “overtly” participated in the acts. The suspension would not affect the demonstrators’ draft eligibility, but those suspended would have to reapply for admission.

The AAS called a conference to discuss the demonstrations. The 400 attending students, mostly white, claimed to “affirm” their responsibility for the unruly behavior as a “community.” No one, however, chose to identify himself individually as an overt participant.

Rejecting whatever punishment the judiciary board levied, AAS members demanded that the university recognize a Black Judiciary Committee. Consisting of four black students, two black professors, and two white professors, the Judiciary Advisory Committee for Black Students was formed to oversee cases dealing with black students.

The AAS’s refusal to be judged by the traditional judiciary committee was not a new response for black student activists, but Dartmouth’s response in recognizing a black judiciary committee was unique to the Ivy League.

Shockley Comes to Town

Students and faculty were reacting much differently.

Then in 1969 Nobel prize–winning physicist William Shockley visited the campus. Shockley had moved from physicist to inventor to racial theorist in an effort to prove that black people were genetically inferior to white people. Propagating eugenics, Shockley claimed that the less intelligent black race was breeding quickly and weakening American civilization. He brought that message to Dartmouth at the National Academy of the Sciences Conference that the College hosted.

But every time Shockley attempted to read his speech, an interracial group of students clapped loudly, interrupting him and drowning out his voice. Consequently, Shockley was unable to share his paper.

When the Dartmouth Committee on Standing and Conduct placed 17 black and white students who had participated in the disruption on college probation, the eight-member Judicial Advisory Committee for Black Students resigned in protest.

It was clear that students (and faculty) in the late 1960s were reacting much differently to white supremacists than they had earlier in the decade. The students completed their probation without any further incidents.

The Groundbreaking McLane Report

“Tradition alone is a vacuum.”

While Dartmouth students, faculty, and administrators debated the racial issues on campus, the nation reeled after the April 4, 1968, murder of Martin Luther King Jr. Distraught and disillusioned citizens across the country rebelled in a hundred cities, illustrating their frustration with racism.

After black students took over the campus radio station to express their anger and disappointment with the assassination, the trustees of Dartmouth could not help but recognize the crucial nature of poor race relations in the post-King era and predictably established a committee to investigate the racial climate on campus.

With former acting college president and retired trustee John R. McLane ’38 chairing the committee, the Trustees’ Committee on Equal Opportunity delivered its report, called the McLane Report, in December 1968. It is notable that its observations did not come exclusively from students but also from those who were in charge of the college.

As the report stated, “we as a committee have tried to envision what Dartmouth should do for the disadvantaged student, particularly the black” student. Although the trustees of other Ivy institutions were concerned with “disadvantaged students,” none submitted a report as extensive as the one Dartmouth trustees created regarding African Americans.

It was quite significant that the trustees, the elite of college officials, took the initiative to research and address the issues of black students, in that it brought the Black Power agenda to the white boardroom and got results. The report described the unpleasant experiences of black students. After revealing that campus life for many was a struggle because of their isolation and the shock of such a new experience, the McLane Report proposed suggestions to improve campus life.

By even forming the committee, Dartmouth officials placed the institution well ahead of some of its Ivy peers. At Columbia, one was not formed until after students took over campus buildings and initiated strikes. The Dartmouth study contended that elite institutions like itself thrived from tradition, but that “tradition alone is a vacuum.”

Using that as a point of departure, the committee suggested that all those affiliated with Dartmouth “must be exposed to a greater understanding of the black, his culture, his history, his goals, his problems, and his frustrations” in order to defeat racism on campus and in the nation. This, of course, had been the suggestion of the AAS.

The report revealed much. It noted that the challenges to enrollment were the small number of “qualified” student applicants, the isolation that Hanover presented for black students from urban areas, the competition with other schools for top black students, and the fact that there was no black administrator to help recruit African American high school students.

The McLane Report suggested how to eradicate those impediments to enrollment, and it is notable that it was the trustees and not administrators who came to these conclusions. At institutions like Cornell and Princeton, administrators ranging from presidents down were usually charged with solving such problems. The trustees of elite colleges and universities were often captains of industry and influential in larger American society. Having access to such figures gave the black Dartmouth students an advantage in negotiating.

Dating Dilemma

“Such bleak prospects could dissuade many a young man…”

A particularly enlightening observation of the committee was that there were few black women in Hanover and none at Dartmouth. This situation presented a special problem for the social lives of black men at the institution. College regulations stipulated that students receiving scholarship aid could not have cars on campus. In following that rule, many of the black students lost the mobility necessary to meet women off campus.

R. Harcourt Dodds ’58, who would later become the College’s first African-American trustee, remembered that while his white roommate maintained a healthy dating schedule, he had far fewer opportunities to court. “The black students had discovered that there was, in fact, a black family in Hanover and there was a teenage daughter in that family who, as one might imagine, became enormously popular,” Dodds recalled.

The isolation of Dartmouth made the experience of black students different than that of their peers at other Ivy schools that either had higher numbers of black students or were set in cities that had large black communities. Dating may have seemed normal to white heterosexual college men, but at Dartmouth such an act was out of the reach of their black classmates.

If black men wanted to date within their race, they typically had to go to Boston or wait for black women from other schools to visit Dartmouth. Such bleak prospects could dissuade many a young man from attending school in Hanover. To shore up the local gender disparity, the report suggested an on-the-job training program be established at the college and any other local institutions that could attract black women.

With the number of open secretarial, nursing, and service positions available in Hanover and on campus, the committee believed that it could help the larger problem of black employment by providing jobs. In addition, the committee suggested “an incidental advantage . . . would be that a number of black girls would be brought for one-or-two year periods.” This was not a problem that black men confronted at other Ivy institutions.

“A Very Exciting Place to Be”

They did not need advice from white administrators.

AAS members took the remarkable step of directly recruiting other African American students to come to Dartmouth. The efforts of the AAS and the college appear to have been fruitful. An article in the Boston African-American newspaper The Bay State Banner reported in the fall of 1968 that “a record 29” black freshmen enrolled at Dartmouth. That brought the number of black students at the college to 89.

This number was lower than that at Dartmouth’s peer institutions, but the total number of students at Dartmouth was also lower. For instance, Columbia had accepted 58 black freshmen, Penn enrolled 62, Yale enrolled 43, Harvard enrolled 51, and Cornell had more than 200 black students enrolled that school year.

But as Dartmouth AAS leader Bill McCurine ’69 pointed out, “In terms of action, more has been done here in the last three years than on any other campus that I know.” Praising his school, McCurine said that Dartmouth was “a very exciting place for a black student to be.” The AAS leader, originally from the South Side of Chicago, served on the Trustee’s Committee on Equal Opportunity and became a Rhodes scholar after graduating.

As the AAS ascended, Dartmouth officials attempted to understand the students’ methods to prevent the troubles that occurred elsewhere. Charles Widmayer ’30, biographer of John Sloan Dickey, explained that after observing the weeklong building occupations at Columbia in 1968, both the radical students and the Dartmouth administration had learned lessons: “It (the Columbia crisis) alerted college administrators to be prepared to handle this new development in the protest movement.” Widmayer claimed that because of this awareness, Dickey and Dartmouth “were ready to handle . . . [disruptions and demands] promptly, firmly, and humanely.”

That did not, however, mean that the president agreed with the students’ movement for Black Power. Dickey noted that “having been in the cause of Negro ‘liberation’ 20 years ago as a member of Truman’s historic Committee on Civil Rights . . . and having won a few battle stars since then,” he added, “I have no reason to be hesitant about saying that this kind of ‘political bluster’ (the call and demonstrations for Black Power) is a tragically ill-advised disservice to the cause of righting the worst wrong of America’s proud history.”

Dartmouth’s black students contended that their approach had changed in the two decades since Dickey’s turn on Truman’s committee. They also stressed that they did not need advice from white administrators regarding black concerns—they needed action.

The trustees’ committee hoped that “the effect of the Black Power Movement in encouraging the black students to associate exclusively with one another may be only temporary.” By assisting the students with resources and by recruiting more African Americans, the trustees and other college officials tried to steer them toward eventually integrating and interacting more with white students. “Once the black students are more significant in numbers and are able to lead from strength, meeting white students as equals, more genuine integration may occur,” the committee noted.

That the trustees acknowledged the presence of Black Power illustrated both the officials’ awareness of the period’s cultural environment as well as a sign of the students’ new identity as representatives of the movement. Further, by making the issues clear to school officials, Dartmouth student activists accomplished what at other schools took takeovers and occupations. Dartmouth’s trustees and administrators learned from the communication gaps that existed between other institutions and their students.

“Nothin’s a game”

Identifying the need for urgent change.

By 1969, Dartmouth’s bicentennial year, black students had come under national scrutiny. An article in Ebony featured song lyrics, written by Gregory Young, that used rhetoric to call Dartmouth black men to action. Entitled “Song to My Brother at Dartmouth,” several lines went “Don’t git caught up in the enemy’s camp, eatin’ his food, thinkin’ his thoughts.”

Encouraging the AAS to take a more militant stance, the song exclaimed: “chump! . . . ya brothers at home, poisoned, dyin’ in the streets. . . . Niggers up at Dartmouth ‘being cool.’ Acting ‘ra-tion-al,’ pla-yin’ the role—Nothin’s a game, my brother! . . . Dyin’s for real!”

The song indicated that those outside of Dartmouth counted on privileged black youth within the institution to use their Black Student Power to improve the lives of all black people—especially those in the ghetto. Considering their location and cultural environment, the college’s black students acted militantly in their own ways to meet these challenges.

Perhaps inspired by the Ebony piece, in 1969 representatives of the AAS sent a letter to President Dickey that identified the need for urgent change with regard to the college’s relationship to black people on and off campus. It listed a number of proposals that included increased black admissions and a Black Studies program.

“As black students, one of our uppermost concerns is the College’s social commitment to the black community,” the letter read. The AAS believed that this commitment could be “manifested in (Dartmouth’s) recruitment and admissions policies and in the living circumstances of the black student on campus.”

AAS members did not barricade themselves in buildings as black student groups had done at Penn, Cornell, and Columbia, but the society still emphasized the need for urgency. Fully cognizant of the events unfolding at peer institutions, Dartmouth officials responded accordingly.

The ’70s See Great Gains

“The second highest percentage of black freshman…”

Due to the activity of the new generation of students, Dartmouth officials made policy changes regarding college life and the curriculum. In 1975, Dartmouth revisited its commitment to equal opportunity by forming another Trustees’ Committee on Equal Opportunity. That the college made the decision to form the committee shed a positive light on the institution for its ability to self-evaluate.

The new committee consisted of trustees, faculty members, alumni, and students. It attempted to measure the college’s progress with respect to black admissions and campus life in the years since the release of the McLane Report. The members of the new committee commended the college for increasing the number of black students on campus.

A good deal of the credit for the increase should have gone to the African Americans who assisted in the recruitment effort and strategies. Indeed, convincing urban black youth to spend four years in starkly white Hanover took cooperation.

By 1975, Dartmouth had employed an action strategy to admit more black learners and women. With black students making an internal push at the college, the plan included hiring black admissions officers and making use of the Black Alumni Association.

After implementing the strategy, the overall enrollment of black students shot up to 376. Of that number, about 50 had participated in the A Better Chance program. Consequently, black students made up 7.8 percent of the class of 1979, which according to the committee, which meant that Dartmouth had “the second highest percentage of black freshman among Ivy League colleges.”

The work of concerned black students and progressive-minded college officials markedly improved the racial diversity of the student body. Part of the population increase was a result of Dartmouth’s move toward coeducation, which led to the admission of black women, who made up 30 percent of the black student population in 1975. The black female students’ presence addressed one of the problems that the McLane report identified as an impediment to retention.

Black students addressed other aspects of college life as well. As a result of previous efforts, they could rush campus fraternities and sororities freely, but many chose not to. Those who did pledge a fraternity often chose Alpha Phi Alpha, the first black collegiate fraternity that Dartmouth recognized. Starting in 1973, it allowed black students the opportunity to socialize among themselves while living in a mostly white setting. It is significant that Dartmouth had finally amassed enough black students to offer the option of a black Greek-letter fraternity to its college men.

When Malcom X Visited

“…Sit down and live together in peace…”

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, black students at Dartmouth and on campuses across the nation had established new identities and began the push for spaces to express themselves.

The Dartmouth administration allowed students to use a building on campus as a center for black culture and residential space. With communication lines increasingly open, the college’s trustees allocated $10,000 toward the arrangement of the center, which was situated in Cutter Hall.

The hall, where Malcolm X spoke in 1965 (weeks before his assassination), also acted as a de facto black dormitory for a time. Later, under pressure from black students, the college renamed the Afro-American Center the El Hajj Malik El Shabazz Center.

The establishment of a black cultural center was not particularly unique for a university or college; however, naming a center after Malcolm X was outstanding for the times. Although he clearly enunciated a love for blackness and a push for black empowerment, in much of America (particularly white America) Malcolm X represented black hate to white people. Furthermore, to many, he certainly did not represent a figure after whom an Ivy League institution should name a student center.

When at Dartmouth, though, Malcolm X’s message was anything but hateful. In an interview with the campus radio station he explained, “when humanity looks upon itself not as black men, white men, brown men . . .but as human beings, then they will sit down and live together in peace. . . .The only time you’ll have a society on this earth when all men will live as brothers will be when all men respect each other and treat each other as brothers.”

By naming a building the Shabazz Center, Dartmouth recognized Malcolm’s personal transformation after his hajj to Mecca as well as his significance in American history. The Shabazz Center also symbolized that black students expected acceptance on their own terms.

While Dartmouth made advancements in admissions and the campus climate, the establishment of the college’s Black Studies program was also significant. In the late 1960s, black students across the nation and at Dartmouth called for recognition of Black Studies and took drastic measures to institute programs and departments. In heeding the call at Dartmouth, the McLane Report suggested the establishment of a program as soon as possible.

To be sure, Dartmouth was not the first of its Ivy peers to establish a program, but it is noteworthy that one of the smallest Ivy institutions (in a starkly white town and state) saw the need to augment its traditional curriculum to include a regimen of courses regarding black history and culture.

Dartmouth established its Black Studies program in 1970, with Professor of Errol G. Hill as its director. Between the1968 McLane Report and the 1975 report by the Committee on Equal Opportunity, the Dartmouth faculty created or modified about 30 courses that dealt with the black or Third World experience. The Black Studies program itself listed six new courses, which added to the potential body of knowledge for all Dartmouth students. Additionally, the establishment of the program at Dartmouth and elsewhere led to the recruitment of black faculty, which likely aided retention.

Dartmouth’s Black Studies program, however, came about without the campus rebellions that took place at San Francisco State, Harvard, and Yale. As part of the institution’s affirmative action plan, the trustees set an employment goal of 10 percent minority faculty hires in the years between 1972 and 1982. The college succeeded in that effort due in large part to the Black Studies program.

Such a goal could not have been achieved without the assistance of black students who, with their deliberate agitation and comparatively peaceful approach, communicated the need for Dartmouth to participate in the black freedom movement.

“A Model…for Guidance”

Remarkable change in a “conservative colonial institution”

During the 1960s, in direct challenge to its reputation as an exclusive white fortress, Dartmouth experienced the invasiveness of social movements in much the same way as its Ivy League peers. Students like R. Harcourt Dodds ’58 and the members of the AAS advanced the causes of civil rights and Black Power and made the movements tangible in the isolated hills of Hanover. These students influenced the elite college to reevaluating its role in creating equal opportunities on campus and in society. That so few students were able to change a conservative colonial institution is remarkable.

Dartmouth’s policy changes benefited the institution in several ways. First, they led to an intensified recruitment effort of black students, faculty, administration, and staff. Second, the changes brought Dartmouth a Black Studies program that allowed the college to be competitive in its course offerings with peer institutions. Third, white and other non-black college affiliates benefited from the presence of the black culture center, people, and subjects.

If one believes the skewed view that Black Power necessarily meant violence in rhetoric and action, then Dartmouth black students were not representative. If, however, one takes the more nuanced view that Black Power was an ideology used to achieve tangible goals on behalf of black people, then Dartmouth students succeeded in their movement for Black Student Power.

The case of black freedom at Dartmouth illustrates how traditionally white liberal institutions had to change if they were to manifest their goals of fairness. The changes that Dartmouth made prevented the college from experiencing the building takeovers, violence, and disruption that other Ivy League universities suffered.

With President Richard Nixon’s “law and order” providing context to the period, Dartmouth was able to maintain peace and relative tranquility. A 1969 article about the potential for violence at Dartmouth claimed that one reason for peace until then was “the quality of student leadership. . . .One must credit Dartmouth’s Afro-American Society which, with confident and consummate diplomacy, has set an effective precedent of non-violent action.”

Nearly four decades later, former AAS leader Wallace Ford II ’70 explained: “I was not a militant. . . .I was very vocal, very committed to the things I believed in.” To be sure, though, Ford and his fellow student activists were comparatively militant, considering the space they occupied, and it helped them to negotiate, demand, and effect “some major institutional changes at Dartmouth,” as Ford later recalled.

Dartmouth officials learned from observing peer institutions. They succeeded in maintaining the safety of Dartmouth’s campus by cooperating and communicating effectively with black students. Fully aware of the relative peace, civility, and understanding that black and white college affiliates exhibited, the AAS noted in 1969 that, “Dartmouth [was] a model to which other institutions can turn for guidance.”

Indeed, Dartmouth College provided an example of how black youth helped an elite white institution effectively deal with the racial instability and changes of society in the decades after World War II.

Stefan M. Bradley is Associate Professor and Chair in the Department of African American Studies at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. He is also the author of Harlem vs. Columbia University: Black Student Power in the Late 1960s.

Excerpted from Upending the Ivory Tower, New York University Press, (September 2018) 464 pp., $32. For a 30 percent discount and free shipping, order direct from NYU Press and use the code ALUM18.

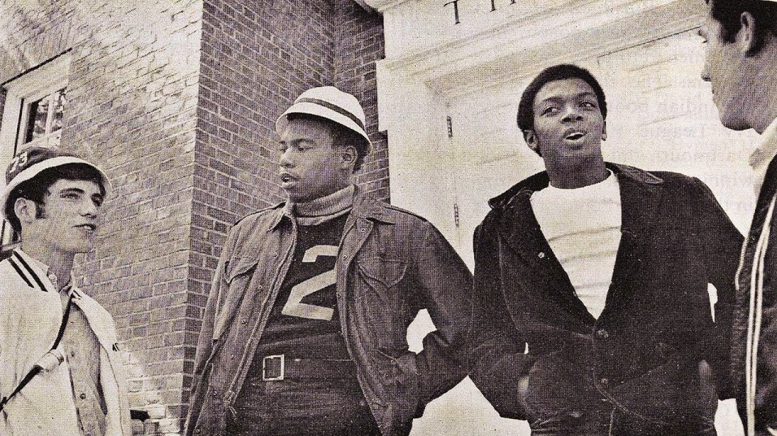

Header image: George C. Riley III ’73 (second from left) and Derek J. Rice ’73 (second from right) speak to classmates in 1969.