The Book That Changed My Life

Jesse Casana

Anthropology

The Inheritors by William Golding (1955)

As a thought experiment in my classes I sometimes ask students to consider what our relationship would be with Neanderthals if they were alive today. Would they vote, drive, and marry us? Would we keep them in zoos? Would they be our slaves? Our food? How we answer those questions reveals as much about ourselves as what we know about our extinct cousins. The archaeological record reveals a lot about Neanderthal behavior and our interactions with them over the few thousand years we coexisted, but much of the human story—the struggles and joys and loves and losses—is left to our imagination. That’s why I love this book by the author of Lord of the Flies. It invites us to share the thoughts and experiences of a Neanderthal family as they encounter a mysterious and dangerous new species: Homo sapiens. Golding’s empathetic exploration of the Neanderthal mind forces us to ponder what it means to be human.

Devin Singh

Religion

The Crucified God by Jürgen Moltmann (1974)

This book by one of the 20th century’s most influential theologians demonstrates meticulous, erudite scholarship in religion and theology that speaks powerfully to perennial questions of suffering, evil, and injustice in the world. Its central message that power is demonstrated in weakness and humility and that the divine is best glimpsed in moments of compassion, vulnerability, and solidarity with the marginalized is one that our modern age continually needs to hear. The book influenced the development of liberation theologies around the world. It also set me on the journey of scholarship in religion and informed my own quest for meaning in this life.

Peter J. Lewis

Philosophy

Quantum Mechanics and Experience by David Z. Albert (1992)

In 1992, I was in my third year of graduate school and feeling lost. I had made the switch from an undergraduate degree in physics to a Ph.D. program in philosophy because I wanted to write about the philosophy of physics. Albert’s book was a revelation: minimally technical, full of insight and wit, and, most of all, completely, transparently clear. He cuts through the needless technicality of a lot of work on quantum mechanics to present an urgent puzzle: Quantum mechanics is the most predictively accurate theory in the history of science, but we have no idea how to understand it as a description of the world. Suddenly, I could see clearly how problems in the foundations of quantum mechanics were connected to issues in philosophy more generally, issues concerning the nature of the world and our experience of it. As soon as I started reading it, I knew I had found my direction. I’ve been headed that way ever since.

Robert St. Clair

French

A Season in Hell/Illuminations by Arthur Rimbaud (1873, 1886)

My life was literally changed by a book and by a mistake, a literal lapsus, or slip. I was 17 and was rousting about in the poetry section of a San Francisco bookstore for a copy of Rilke’s Duino Elegies. My fingers went one volume too far. I happened across the name Rimbaud and a volume of prose poems whose title was exactly the sort of thing a 17-year-old is bound to notice: A Season in Hell/Illuminations. It wouldn’t be much of an exaggeration to say I’ve been reading this book ever since. On occasion, I can’t help but wonder where I would be if my finger hadn’t skipped a volume, a poet, a letter from Ril to Rim. I went to college a year later. I began to learn French and read Rimbaud in the original. I met the woman I ended up marrying, followed her to France, and we now have a son who is 8 and weird and wonderful. Talk about changing one’s life—I shudder to think what might have been had I picked up the book by Rilke instead.

Peter Doyle

Mathematics

The New Streets and Roads by William S. Gray, et al. (1956 edition)

As Thoreau wrote, “How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book.” I have not, not from reading Walden or any other book, unless you count the Dick and Jane books and other books from which I was taught to read. Learning to read changed my life big league. Some of those first stories struck deep. I recently tracked down The New Streets and Roads, my third-grade reader, and found the story “The Fairy Shoemaker” about young Tom. He tied his yellow tie around a tree to mark the fairy’s pot of gold and made the fairy promise not to remove it. When Tom got back with his shovel, every single tree had a yellow tie around it. How clever. I recently read Boccaccio’s Decameron and was astonished to find this same trick was played on King Agilulf in a story adults didn’t think we were ready for in third grade.

Leslie Butler

History/Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies

Jailbird by Kurt Vonnegut (1979)

One summer as a teenager, I read what was probably not the typical gateway into the Vonnegut corpus, but something about it clicked with me. Mordantly funny and almost unrelievedly dark, the novel offered a curious and bizarre excursion through the 20th century from the trial of Sacco and Vanzetti to Watergate. It struck me as a serious novel, brimming with ideas, and it plunged me, over the following 18 months or so, into a fairly intense if poseur-ish Vonnegut phase that, in retrospect, I think was formative in taking my academically uninspired, high-school self seriously as a thinker. I haven’t read any Vonnegut in decades, but I look back at Jailbird as the transformative book that got me excited about ideas and thus fundamentally prepared me for college.

Laura McPherson

Linguistics

The Power of Babel by John McWhorter (2001)

In high school I had the lucky accident of picking up a copy of The Power of Babel. I had always loved learning and studying languages, but this book was the first time I had read about language as a human phenomenon. With humor and wit, McWhorter takes the reader through the history of human languages and how they evolve, split, merge, and even die. Drawing examples from languages around the world, the book is a great introduction to some of the key concepts of linguistics and is one I continue to this day to recommend to friends or students looking for a better understanding of what I do.

Jonathan Chipman

Earth Sciences/Geography/Quantitative Social Sciences

Cartographic Relief Presentation by Eduard Imhof (1982)

I first encountered Swiss mapmaker Eduard Imhof’s textbook in 2009 while looking for ideas for a new cartography course. I knew right away I wanted students to learn landscape visualization as both an art and a science. His book is technically obsolete, but its vision of lovingly detailed mapping of topographic relief—the shape of landscapes—is still inspirational in the modern world of digital cartography and geovisualization. Technological advances have made it easy to churn out ugly maps. Students who want to do better should look back at examples from the golden age of alpine cartography. In my “Geovisualization” class, I show students [famed cartographer] Bradford Washburn’s astonishing map of Mount Everest, which employs techniques from Imhof’s book. The closer they look, the more fascinated they are by the ways cartographers can convey the feel of a landscape. We design maps and geovisualizations differently now, but we still need that inspiration.

Desirée J. Garcia

Latin American, Latino, and Caribbean Studies/Film and Media Studies

Sister Carrie by Theodore Dreiser (1900)

Dreiser’s novel about a country girl who migrates to the city, encounters hardship, and rises to stardom struck me as very modern when I first read it nearly 100 years after its publication, in 1998. I was undergoing my own migration from the green valleys of Oregon to urban Boston. Along with Dreiser’s protagonist, I experienced the city’s assault on the senses and alienation and anonymity, as well as the “metropolitan whirl of pleasure” in department stores, restaurants, and theaters. Carrie’s journey—and my own—demonstrated the interconnectedness of urban space, identity, and social mobility, especially for young women. In particular, Dreiser’s representation of popular theater, in which Carrie rises from chorus girl to star, inspired me to pursue a career writing and teaching on topics of gender, migration, urban space, and musical performance.

Josh Compton

Speech

Speech Making by James A. Winans (1938)

Imagine my delight when I discovered that one of my mentor’s treasured rhetoric books—one I inherited after his death years ago—was written by James Winans, a professor of public speaking who taught here a century ago. Speech Making changed the discipline: It introduced dialogue as the metric for good public speaking, rejecting the idea that speech was a simple skill, an artificial performance. His book changed me, too. For a kid with a stutter, perfect fluency was out of my reach. But a good idea, expressed with conviction and clarity, was not. Yes, I still like it when my writing sings, when I get close to eloquence. But even more satisfying are those moments when my audience understands my argument, even when it disagrees, and I understand my audience better, too. That sounds like great public speaking. That sounds a lot like dialogue. And as Winans and my mentor taught and I now teach—those two things aren’t so different after all.

George Cybenko

Engineering

Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn by Henry Miller (1934, 1939)

This might seem an odd choice for an engineering professor, but when I was in high school in Toronto these books showed me that countercultures existed long before the 1960s. They opened me up to thinking about life differently and more adventurously. My friends and I thought we were cool, hip outsiders, but reading Miller gave me a whole new sense of what being a cool, hip outsider really meant. Although these books were originally banned in the United States, they are tame by today’s Fifty Shades of Grey standards. Reading them when I was an undergraduate was an antidote to majoring in math. They also prepared me well for the New York area’s eccentric artist communities, which I fell into during my graduate studies. I spent many evenings with delightfully creative and unusual people. Many of them could have walked right out of Miller’s books, and I remember those days as a magical time in my life.

Brenda Garand

Studio Art

Eva Hesse by Lucy Lippard (1976)

Eva Hesse has resonated with me throughout the years. I first read it in 1981 when I was a 21-year-old grad student in sculpture at Queens College, City University of New York. Hesse’s ex-husband, Tom Doyle, was my sculpture professor, and never having had any female professors for sculpture or for any studio art class for that matter, I devoured this book. Hesse was one of the most influential sculptors of the 20th century. An immigrant from Germany, she passed away from a brain tumor in 1970 at the young age of 34. This book tells the story of her life, her work, drawings, paintings, and sculpture and her struggle to come to terms with being a female artist. What I appreciate most are its excerpts from her diary: her voice, thoughts, and drawings of her quest to make sculpture that changed the world.

Justin V. Strauss

Earth Sciences

Encounters with the Archdruid by John McPhee (1971)

I read this book in high school, and it changed the trajectory of my career from medicine to geoscience. McPhee explores the surprising commonalities and differences between environmentalist David Brower and a mining geologist, a real estate developer, and a dam engineer as they explore the wild forests, rivers, mountains, and coastlines of the United States. While nominally nonfiction, this book portrays how people on different sides of the aisle can peacefully and productively agree to disagree about polarizing topics, something that seems more and more relevant these days. It also explores the terribly fine line between development and resource extraction to support mankind and the need to preserve wild places on our planet. As we grapple with major changes in the environmental stability of the earth and the continued need to extract mineral and petroleum resources to fuel our green technological revolution, this book has become even more relevant.

Miya Qiong Xie

Chinese Language and Literature

Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History by Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub, M.D. (1991)

This book is about how the critical reading of literature bears witness to personal and historical trauma and to the Holocaust in particular. It gave my interest in literature as a healing art scholarly rigor and intuition. It allowed me to make sense of moments of silence in modern East Asian literatures, especially those written by women, and to further empower those moments through critical reading. The book motivated me to pursue a higher degree and an academic career in the authors’ country, the United States, which I had never visited. In all those ways, it made me who I am today.

Sachi Schmidt-Hori

Japanese

The Tale of the Heike translated by Royall Tyler (2012)

Based on the 12th-century civil war between the Minamoto and the Taira clans, this 13th-century work by an anonymous author is Japan’s most beloved martial epic. Narrated by a Buddhist priest who reminisces about the five-year ordeal that robbed the lives of tens of thousands, the focus of the tale is not the glory of the victors, the Minamotos, but the futility of human pursuits of wealth and power. With numerous episodes of brutal bloodshed as its backdrop, the true gems of The Tale of the Heike are the handful of female characters who bravely turn their backs on violence and worldly fame, eventually attaining rebirth in the Buddhist paradise. Although I was exposed to the book’s famous battle scenes in middle school, it was not until my adulthood that I read it in its entirety and became newly aware of the Heike’s powerful pro-woman, anti-violence messages, which are extremely relevant in America’s current politico-cultural climate.

Tarek El-Ariss

Middle Eastern Studies

The Tiller of Waters by Hoda Barakat (2001)

This book best captures the experience of war and human resilience in the midst of destruction. I read it as a graduate student in 1999. It tells the story of Niqula, a man who moves into his father’s textile shop in the bombed-out and abandoned downtown area of Beirut during Lebanon’s civil war. There he reinvents his life among the ruins, befriends wild animals, and meets a woman, Shamsa, with whom he starts a relationship. To counter the effects of war and confront the history of sectarian conflict, Niqula tells Shamsa the history of textiles, moving from linen to cotton and ending with velvet and silk. This history doubles as a narrative of seduction and survival that asserts humans’ ability to dream and love against all odds.

Lewis Glinert

Hebrew

The Talmud

I don’t know what impelled me to open a heavy volume of The Talmud on the quad at Magdalen College Oxford that October day in 1968, gathering about me a bemused circle of freshers—Jewish? Gentile? You think I knew?—and expounding the thoughts of ancient sages. It was 1968, and, of course, anything was possible, even for a working-class Jewish kid with self-consciously collar-length hair. But this wasn’t one of the musty, old Talmudic tomes from the college library, the sort my grandfather studied every day and I didn’t. This was a new-look Talmud with punctuation and formatting, one I could read for myself and thirsted to read—enriched with archeology, biology, illustrations and maps and indices, the text rendered in modern Hebrew and packaged in a snazzy jacket. The brains behind it was the young Adin Steinsaltz, an Israeli rabbi hailed as a “once-in-a-millennium scholar.” The multi-volume Steinsaltz Talmud was to open up traditional Jewish learning—its subtleties and debates and socio-legal realism and lofty ideals—for a contemporary world. It swept me up. This was 1968, and anything was possible.

Petra S. McGillen

German Studies

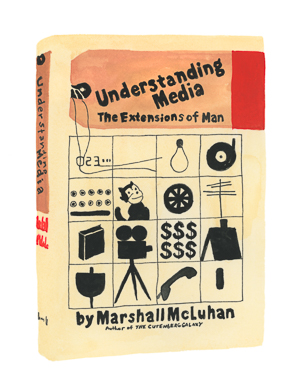

Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man by Marshall McLuhan (1964)

I was in my second year of college when I first encountered McLuhan’s Understanding Media in an introductory seminar on media theory. It completely blew my mind. I had never read any theory like this—one that made such daring leaps and was so bold in discarding entire modes of thought to put forth its own radically new approach to media analysis. Rather than joining the countless cultural critics who argued over good versus bad media content, McLuhan taught the world that content is nothing compared to the structural effects that our media usage has on all aspects of our being, from the ways in which we think and feel to the social order writ large. Media, as McLuhan has it, are the secret driving forces of history. When I assign Understanding Media in my seminars now, I am excited to see that this brilliant reflection on media technology has lost nothing of its provocative punch and prognostic value.

Illustrations by Drue Wagner