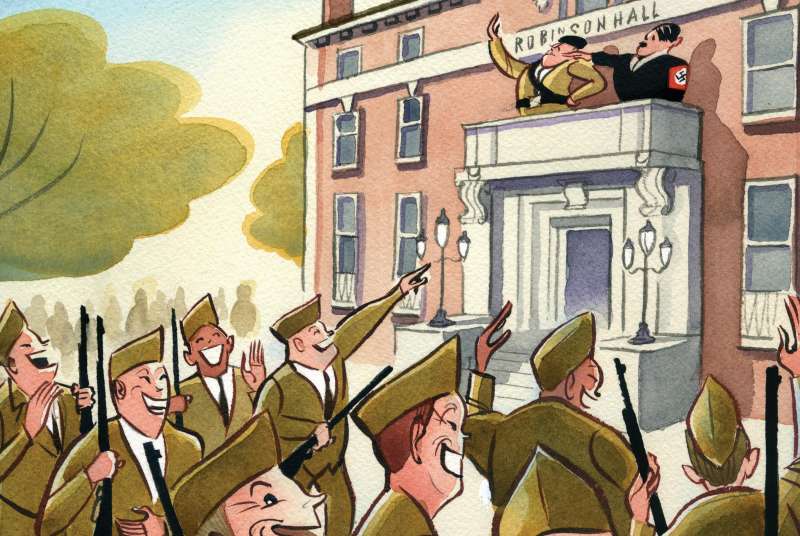

Tyrants on the Balcony

Hanover’s Main Street may have been designed by Grandma Moses, but in the spring of 1959, Grandma had been shoved into a snow-slushed alley by global theater.

On the second floor of Robinson Hall, across from the Green, is a wonderfully wide balcony. The room leading to the balcony faces what was, at that time, the main theater of Dartmouth. Backstage was a tiny stairwell that corkscrewed directly to the basement, where the costumes and dressing rooms were set. For my roommate William “Gatz” Hjortsberg ’62 and me, it was going to serve as our entrance—and escape route.

Court-martialed by Air Force ROTC at UCLA for never finding my marching “flight,” I arrived in Hanover as a freshman, ready for yet another comic turn with the world of soldiery. On the day of the Armed Forces Day parade, Main Street was filled with parents, children and members of the faculty. Even the Senior Fence had undergraduates, wives and kindergarteners hanging on its rails, waiting to see ROTC cadets march around the Green.

Gatz and I had decided to dress as Axis partners—with Gatz as Hitler, I as Mussolini. At the height of the parade we would burst upon the balcony, offering a noisy review of the troops as they passed below.

In the basement of the theater we had assembled two odd-looking costumes: Gatz took a black uniform and fashioned red piping and a swastika armband. I prepared a light brown outfit for Mussolini with a tasseled black fez. The stuffing for Benito’s girth was easy enough, but Gatz was tall and I was short, so I had to add a pair of stuffed boots to my wardrobe to add a little height. Gatz said that he would stand back a little from the stone railing to provide “a bit of Renaissance perspective.”

“I don’t know,” I replied. “We have to enter together. Then you take the right side of the balcony and I’ll take the left. After the harangue, we’ll stand together again, salute everybody and get the hell out.”

We were planning to double-talk German, which we had practiced in our dorm room, and had decided we would wait until we saw the student-soldiers come toward us. As soon as half of them had passed Robinson Hall, we would rush to the balcony. If we were threatened, we could dash across the hall and into the theater, running behind the curtain, then careening down the back stairs, like starlets from Gold Diggers of 1933, to the dressing-rooms. There we could dump the costumes, leave Robinson by the back door, cross the street and enter Thayer Hall to mingle with other students.

On the day of the parade we snuck into the theater, took our costumes from the rear of the costume cabinets, then changed in semi-darkness. Next, we pulled out a makeup kit and Gatz gave himself a Hitlerian moustache. Immediately, his light blue eyes began to look both plaintive and lunatic. I stuffed myself, pulled the collar of my beige coat up to my ears until I had an enormous chin wattle, then slicked back my hair into a single wave.

The entire parade was totally screwed up, with soldiers banging into each other, dropping their weapons.

We examined each other’s costumes and posture. Satisfied, we climbed the spiral stairwell to the second floor, backstage right, in the theater. We could hear the ROTC bands. It was going to be easy to make our appearance at the proper moment, because the Doppler effect of the music told us the approximate location of the marchers as they proceeded mechanically around the Green. We then snuck into the corridor to see that no one from The D or WDCR was hanging around.

The corridor was empty, so we moved slowly across the floor toward the balcony doors. The music still seemed a good distance away. Gatz stood in a corner, by a curtain. I took off the fez, opened the balcony door and strained around the corner to have a peek at Sanborn House.

“Holy shit,” I whispered.

“Holy shit what?” asked Gatz.

“Holy shit, the Green is filled and most of ROTC is in front of Baker Library. We have a couple of minutes yet.”

“Let’s go back to the theater,” said Gatz. “Leave the door open so we can hear the music.”

We peeked into the corridor once again, then moved quickly into the theater. Both of us started to sit by the door, then rose quickly, not wishing to upset our disguises. “You’re an exceptionally elegant Hitler,” I said. “It’s about time someone treated him with respect”—almost channeling the take that Mel Brooks would so memorably put on screen a few years later with The Producers.

“Let’s go,” said Gatz, and we moved slowly across the corridor, through the room. As I peeked once again out the balcony I saw that the line of soldiers marching in front of Robinson Hall was now stretching the length of the Green.

“This is it!” we both yelled. We strode onto the balcony, and I mimed Mussolini, complete with hand gestures. Gatz stood at the other side, screaming dementedly and moving about like a Berlin robot. I began singing “La donna è mobile,” punctuating the lines with arms akimbo, head shaking, finger lifted.

All eyes turned to the balcony.

Members of Navy ROTC were directly below us. Within 30 seconds everyone had broken ranks with laughter. Townspeople turned to the balcony, as did faculty members and children with their parents. Soon the entire parade was totally screwed up, with soldiers banging into each other, dropping their weapons, laughing crazily, and parents applauding and laughing and trying to take pictures.

Suddenly Gatz said to me, in a thick German accent, “Uh-oh, buddy boy! Time to say goodbye!” He pointed at four older, professional officers who were furiously shouting at us and running frantically toward the entrance of Robinson, scattering mothers and babies about them as they zigzagged to the main doors. One of the officers was so furious he was sputtering, swearing, then sputtering again. We both knew he would tear us apart if he caught us.

“Arrivederci, Roma!” I yelled as Gatz and I removed our costumes and makeup and followed our planned escape route: behind the curtain, down the spiral staircase, into our clothes, out the basement door, across the street, into Thayer Hall—soon lost in the dining room crowd. I realized that Gatz and I hadn’t even looked at each other since we were in costume.

I understood at that moment that Gatz was as engaged as only a superb artist could be: focused upon the goal, savoring the moment in order to exploit it. “Amazing,” I whispered over a plate of mashed potatoes and mystery meat. “We stopped the street.”

Gatz raised his eyebrows. “Did we?” he asked.

“Absolutely,” I said. “The center gave way, leaving the right to crumble and the left struggling alone in desolate isolation.”

The next day the phantom Hitler and the ghostly Mussolini were the talk of Dartmouth Radio, the local newspaper and the student body. ROTC demanded that the sinning students give themselves up to College authorities, who said that although the representation of the Axis leaders was obviously a student prank, it was considered to have been executed in very bad taste.

For one week, students debated the right of the mysterious Axis powers to appear on a balcony during the parade. The local paper wrote an editorial on how the two invaders had dishonored all those who had died so that America would continue to have the freedom to dishonor anybody it wished. It was an odd argument. After two weeks the phantom duo was called cowardly by the local paper and boring by The D, because they would not show themselves.

“I didn’t think we were boring,” I told Gatz. “I certainly wasn’t bored,” he said.

“We’ll surprise them yet,” I replied. And surprise them we did: We created a club to address the issues of racism and atomic proliferation, based upon the principles of Bertrand Russell. It was called the Human Rights Society. There were seven of us human righters out of a population of more than 2,500 undergraduates.

Within a decade Parkhurst Hall would be occupied by students, led by another student named Geller, although I’ve never met him. The occupation of Parkhurst would have nothing to do with the Human Rights Society—one of the most wonderfully polite associations formed to address America’s and the world’s social ills. The actions in Vietnam and America’s ghettos had irrevocably done away with the silly tasteful and pushed us into a newer world, where Topsy soon married Turvy and eventually their Tweedledum offspring left their ancient homes to cook on a newer range.

Stephen Geller is a novelist, screenwriter, playwright and director. This is adapted from his forthcoming book, Sabbath-on-Swathe: The Authorized Autobiography.