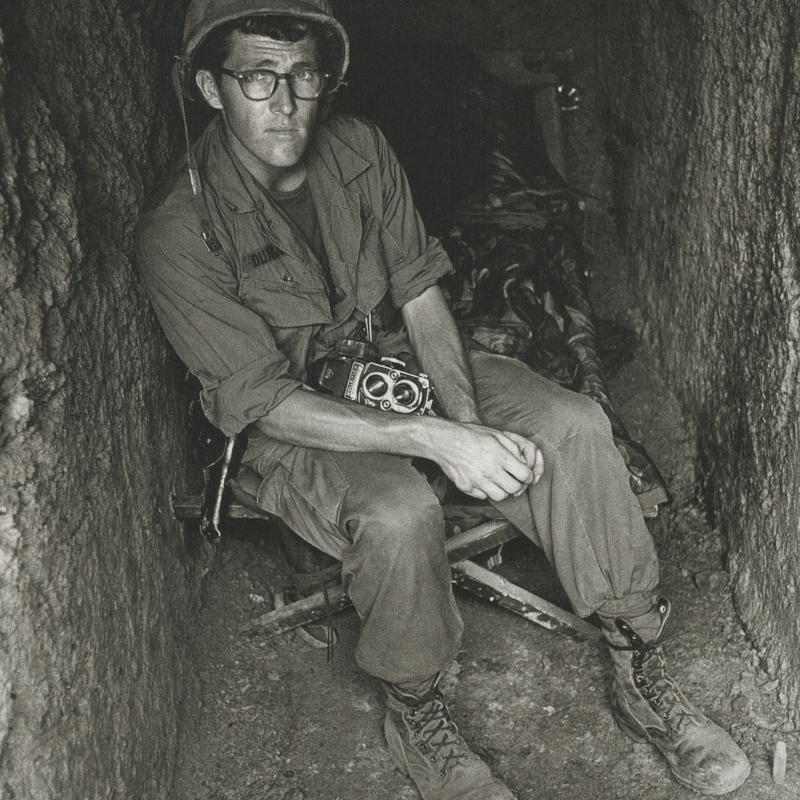

“The Idiocy of War”

Long, unpopular and ultimately a failure, the Vietnam War remained so controversial after it ended that many veterans were loath to discuss their combat experiences in the conflict for decades—even among close family members.

But taboos may be lifting. New books, an upcoming documentary series and a revived Broadway musical, among other works, are directing fresh attention to a war that triggered a tumultuous era that parallels our current polarized age. That newfound interest is being noted gladly by some of the hundreds of Dartmouth alumni who served in Asia and encountered an indifferent or hostile world when they returned.

“The pendulum has swung enormously,” says Tony Thompson ’64, who spent a year in Vietnam with the Army at a punji-stick-ringed bunker by the Ho Chi Minh trail, and later by the North Vietnam border, where he participated in search-and-destroy missions. Neither the Bronze Star nor the Vietnam Cross of Gallantry he earned prepared him for the enmity he faced upon returning to Hanover in 1965 to finish his degree. One night, as he was hanging out in the basement of his fraternity, Gamma Delta Chi, a fellow member called Thompson “a moral coward” for his service.

Stung by a point of view that was gaining traction, Thompson moved off campus to White River Junction, Vermont, for his last two years of studies. “I didn’t wear Vietnam as a badge of honor or of dishonor,” Thompson says. “I still have no regrets.”

“Some would still say the war was a mistake. But there’s finally a realization that the fault doesn’t lie with the guys who were there.”

Other alums, especially those who served later in the 1960s, are more critical of their country’s involvement in the war. They say it was a needless entanglement in a conflict between Vietnamese factions and that it was executed so poorly it turned many combatants into pacifists.

“What I saw was the idiocy of the war,” says Francis “Bud” McGrath ’64. One night in 1967 when McGrath was stationed at an Army camp near Saigon, a noise near the camp touched off an hours-long, bullets-and-bombs assault involving machine guns, howitzers and even B-52 bombers, which were diverted to join the massive strike. When the smoke cleared, a patrol ventured out to find no evidence of any enemy—just a single, dead monkey. “We probably spent $10 million killing that monkey,” says McGrath, who joined anti-war protests when he later moved to Austin, Texas, in 1968 to pursue an English Ph.D. “There were a lot of people over there who didn’t really know what they were doing.”

It’s impossible to pin down how many Dartmouth alumni and students were among the 2.7 million Americans who served in Vietnam between 1964 and 1975. The College only recently started collecting data about military service, so head counts are based on self-reporting and estimates from anecdotes.

A tempting way to measure the College’s involvement is to look at membership in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) programs. By modern standards—Dartmouth’s program now draws fewer than a half-dozen students annually—ROTC was hugely popular in the early 1960s. Almost a third of every class, roughly 200 students, graduated into military service from ROTC each year, says Ed Miller, a Dartmouth history professor whose Vietnam War class, offered since 2005, is usually fully subscribed. “You enlisted and you didn’t think about it,” Miller says. “It was a really significant part of Dartmouth’s social culture.”

Back then, in the day of the Selective Service draft, joining ROTC could be shrewd. Though only about one of every three military enlistees in the Vietnam era wound up in Southeast Asia, the thinking was that those who did go could possibly improve their chances of survival by becoming an officer. “If I was going to be in a war zone, I didn’t want my life depending on someone else’s judgment,” says McGrath, who came up through the College’s ROTC program and spent part of a four-year stint in places such as Fort Huachuca, Arizona, where he trained soldiers.

As public sentiment turned against the war—especially after its deadliest year, 1968, which was tarred by assassinations and riots in America—interest in ROTC waned. In the class of 1968, which consisted of 748 students, just 81 officers were commissioned at graduation by the Army, Navy and Air Force, according to College documents. (Dartmouth does not officially track ROTC membership, and the military does not have accessible historical records broken down by school.)

Even signing up was preferable to getting drafted, says William “Dab” Dabney ’70. After a night of heavy drinking during Winter Carnival in 1968, he drove to Manchester, New Hampshire, and enlisted in the Navy, thinking that would give him better control of his fate. The road trip wasn’t fueled purely by patriotism. Struggling with a grade average that hovered around a C, Dabney, a sophomore at the time, had decided to take a leave of absence and acquire some discipline, even though that would mean losing his student-deferment status.

“I was horrified by the war,” says Dabney, whose father and grandfather were both decorated veterans. “I kept thinking, ‘All my friends at Dartmouth must think I’m a total turncoat, since they’re so anti-military.’ I had real second thoughts.” As a sonar technician, he was able to serve most of his four-year stint on ships in the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

Robert “Obie” Holmen ’72 arrived on campus in the fall of 1966 as a self-described “country boy from Minnesota.” Back then, drugs—if they were around, Holmen says—were mostly used covertly. But in January 1971, when he returned to Hanover after a tour in Vietnam mostly spent as an elite Army Ranger, “marijuana smog was everywhere,” he says. Undergraduates in the mid-1960s were conflicted about Vietnam, Holmen says, but not by the end of the decade: “It was virtually unanimous. People were opposed to the war. Bob Dylan was saying, ‘The times they are a-changin,’ and it was true.”

Holmen, who received two Bronze stars for “valor in combat”—one for beating back a platoon of the North Vietnamese Army with a couple other Rangers—experienced his own change of heart soon after arriving in Vietnam. When shooting erupted into a firefight, he first thought, “My God, from the Greeks and the Romans to the doughboys in France, I’m sharing their experience,” he recalls. “But as the night wore on, that feeling was replaced by fear and dread.” Holmen drew on his war experiences for a 2014 self-published novella, Gonna Stick My Sword in the Golden Sand.

“Vietnam veterans found little validation of their service even after the fall of Saigon in 1975. Everybody avoided discussing it.”

Protests peaked at Dartmouth during the May 1969 occupation of Parkhurst Hall. About five-dozen students and alums barricaded themselves in the main administration building to oppose the College’s ROTC programs. “We didn’t want to see our fellow students trained to be cannon fodder in essentially a racist and genocidal war,” says David H. Green ’71, a varsity lacrosse player who phoned his coach from the occupied dean’s office to say he couldn’t make it to practice. After students refused to obey a judge’s order to leave Parkhurst, police officers stormed the building to find protesters on a staircase, arms linked, chanting “U.S. out of Vietnam! ROTC out of Dartmouth!” Green recalls. One of 54 arrested, he spent 26 days in jail after being convicted of contempt of court and, afterwards, Dartmouth expelled him.

The Parkhurst incident, which led to Dartmouth eventually kicking ROTC off campus in 1973, also ensnared David “Jake” Guest ’66, whose meandering journey through the era suggests how a divisive war shaped so many lives. Suspended after his freshman year for bad grades, Guest enlisted in the Air Force and became a medic in Nuremberg, Germany. “The military and the draft still had a lot of good vibes left over from World War II and Korea,” he says, adding that the threat of death or injury seemed remote. But after three years overseas, where he met soldiers who seemed unhinged by their Vietnam experiences, Guest changed his tune: “It went from, ‘What’s going on over there?’ to ‘Maybe what we’re doing, we shouldn’t be doing,’ to ‘We’re doing the wrong thing,’ to ‘The Vietnamese are the ones who are right,’ to ‘I’m on their side,’ ” he says.

Despite re-enrolling in the College in 1967, Guest was booted again the following year, distracted, he says, by a wrongheaded war and the resulting counterculture. Eventually he and several like-minded alums moved to the Wooden Shoe, a commune in Canaan, New Hampshire. Guest today owns an organic vegetable farm in Norwich, Vermont. “Without Vietnam there wouldn’t have been any of that,” he says of the choices he made. “It was the oxygen that stoked the fire.”

Vietnam veterans found little validation of their service even after the fall of Saigon in 1975. “Everybody totally avoided discussing it,” says Warren Cook ’67, a first lieutenant in the Marines who served as a platoon commander and then in a psychological operations unit. “There was no acknowledgment of what we did,” Cook says. “ ‘Thank you for your service’ was not even in peoples’ vocabulary.”

Frustratingly, he adds, those who showed what he perceived as a lack of interest included his parents, his five siblings and his wife, whom he married in 1970 after returning home and becoming a prep-school teacher. Even World War II veterans were unsupportive. “They told me, ‘You don’t know what war is really like,’ ” he says.

The collective silent treatment exacerbated Cook’s drinking problem, he says, and led him to falsify his resume with a line about winning a Navy Cross, a prestigious war award that’s second only to the Medal of Honor. That fabrication, which came to light in 2003, cost him a job at the Jackson Laboratory, a top biomedical facility in Maine. “I think it was about looking for recognition,” admits Cook, who says that a 2015 trip back to Vietnam was a cathartic step toward coming to terms with his past.

Today the public is embracing historical accounts of the Vietnam War. In April Enduring Vietnam: An American Generation and Its War, a book by former College president Jim Wright, was published to critical acclaim, and in September PBS will air The Vietnam War, a 10-episode documentary from Ken Burns and Lynn Novick (Miller consulted). This year has also brought “Vietnam ’67,” a weekly series of opinion pieces in The New York Times, and the revival of the Broadway musical Miss Saigon, set in Vietnam in the mid-1970s.

A growing sense of pride about that brushed-aside war manifests itself in smaller ways, too, according to Holmen, who says he’s never seen so many people wearing baseball caps with “Vietnam Veteran” emblazoned across the front. “Some would still say the war was a mistake,” he says. “But there’s finally a realization that the fault doesn’t lie with the guys who were there.”

There have long been campus memorials to those who died in Vietnam: In 1975 Smoyer Lounge was dedicated in Thompson Arena to honor the service of former soccer and hockey star Billy Smoyer ’67, a Marine who died in 1968. In 1978 a plaque, later moved to Zahm Courtyard outside the Hop, was installed in Collis and listed the alums “who gave their lives in the armed forces, 1965-1972.” A duplicate went up at Memorial Field in 2015.

Last year, wanting to set the record straight—a move applauded by alums irked by the original wording—Wright and his wife, Susan, underwrote the installation of replacement plaques that honor the alums “who gave their lives while serving their country during the Vietnam War.” In addition to Smoyer’s, the names on the plaque include Michael Spark ’46, Kenneth Hall ’48, John Leaver ’55, Gardner Brewer ’56, Peter Morrison ’64, Bruce Nickerson ’64, Dennis Barger ’65, Stephen Mac Vean ’65, John Seel ’65, Ric Muller ’66, David Nicholas ’66, Duncan Sleigh ’67, John Peacock II ’68 and John Hogan ’69, who were among the war’s 58,220 American casualties. In addition to those 15, also listed are six other alumni who died while serving elsewhere during the war. In comparison, 13 alumni died in Korea and 310 in World War II, according to research by Charles T. Wood, the late Dartmouth history professor.

In 2012 Phil Schaefer ’64, a former class secretary, invited classmates to write essays about their military experiences and received a strong response. The result was Dartmouth Veterans: Vietnam Perspectives, a book that includes stories from 55 veterans in the class of 1964, not all of whom saw combat in Vietnam.

In 2014 Miller, who recently accompanied former Secretary of State John Kerry to Vietnam, launched the Dartmouth Vietnam Project. This ongoing effort seeks to record oral histories of alumni, faculty, staff and residents of the Upper Valley about the period between 1950 and 1975. By late April interviews had been recorded with 101 people, including 73 alums. Of that group, about half are veterans, Miller says, most of whom served in Vietnam.

Sharing their experiences not only with each other but also with fellow alums has provided comfort and validation, many veterans say. Some praise the creation, in 2013, of the Dartmouth College Uniformed Service Alumni, a support and advocacy group. Others hail the spate of recent Vietnam-themed campus talks, such as the one staged in June, during the class of 1967’s 50th reunion, that featured Cook and fellow combat veteran Beirne Lovely ’67; Andy Barrie ’67, who deserted to Canada; Phil Curtis ’67, who served in the Army Reserve after ROTC at Harvard Law; and John Isaacs ’67, who served in Vietnam with the Foreign Service.

The mood at those gatherings has been reflective, not bitter, says Isaacs, now a senior fellow at the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation in Washington, D.C. “There were no recriminations, no expressed feeling that some got a good deal and others had to pay a high price,” Isaacs wrote in an essay for his panel. “All recognized that a terrible war, not of our making, started by national leaders determined to shape large geopolitical developments, forced tough life decisions on young men, decisions that could shape or even end their futures.”

C.J. Hughes is a journalist based in New York City. He is a frequent contributor to The New York Times and a contributing editor to DAM.