Beetle Mania

Matt Ayres has been studying one of the country’s most notorious insect pests—the southern pine beetle—for more than two decades, tracking its abundance and distribution with pheromone-baited traps, aerial surveys and examinations of trees within individual infestations.

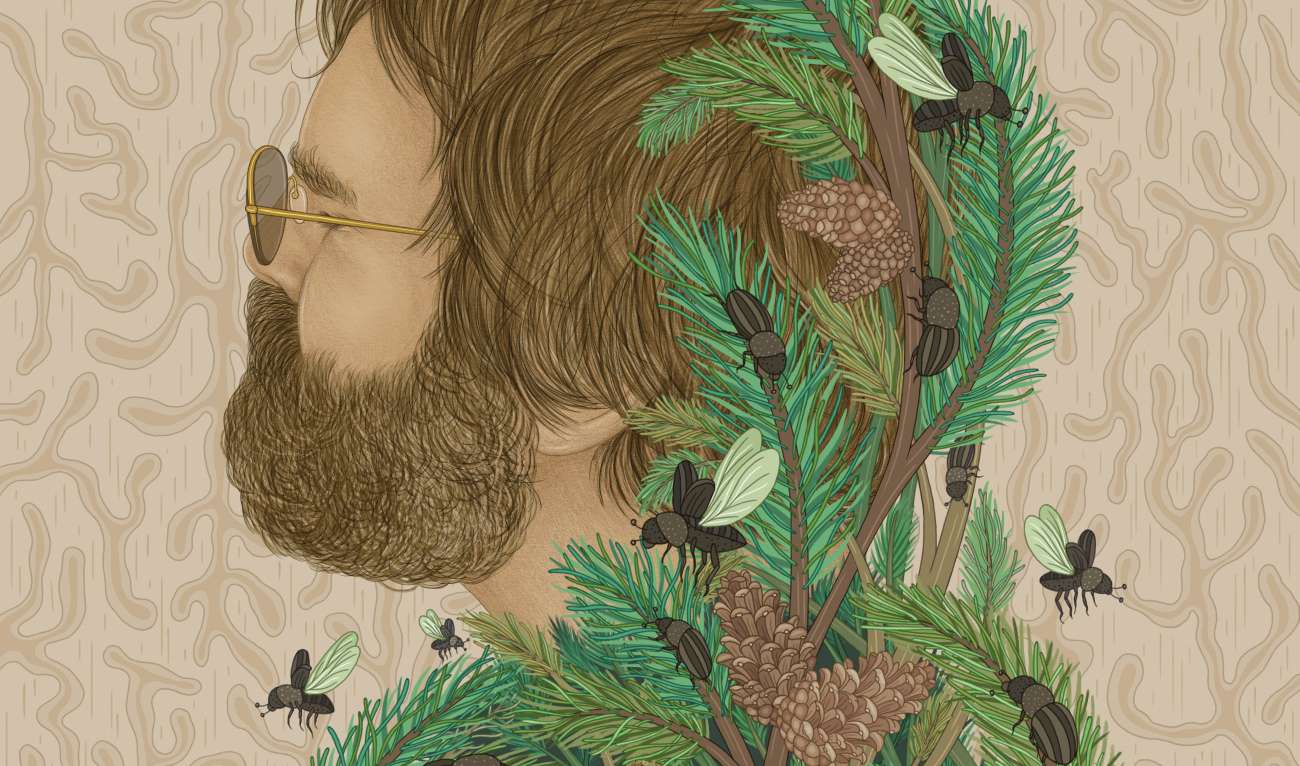

The bearded, shaggy-haired, bike-riding biology professor seems well suited to New Hampshire. But he’s also become an international leader in studying how climate change affects the distributions and impacts of insects. He’s one of the people whom the suits at the World Bank summon for advice regarding ramifications of climate change and invasive insects on international trade agreements. “I had to wear a buttoned-up shirt for that one,” he says with a laugh. “It was not my natural habitat.”

But such professional visits are necessary if Ayres is going to save the world’s trees. In the last several months he’s been working to get his message out. His research, which has implications for everything from pesticide use to international trade, has been featured in The New York Times and The Washington Post.

Smaller than a grain of rice, the southern pine beetle is one of the most aggressive tree-killing insects in the world.

Ayres’ research on the southern pine beetle started more than 25 years ago, when he was hired as a postdoctoral research scientist with the U.S. Forest Service in Louisiana. One of the most aggressive tree-killing insects in the world, the beetle is smaller than a grain of rice but kills trees by attacking in numbers. The effects on the landscape can be seen from space. “Pine trees defend themselves against normal pests by exuding oleoresin from wounds,” says Ayres. “If I were dropped into a vat of pine resin I’d be dead within minutes, but southern pine beetles are not normal pests. They are able to swim through the resin for days, using their six legs, while they excavate galleries within the inner bark to lay eggs that will produce even more beetles in the next generation.”

The beetles rely on mutualistic microscopic fungi in their organs that help offspring survive. When a mother beetle lays eggs, it leaves behind fungi that grow spores for larvae to feed on. Once they mature, the larvae move to the outer bark of the tree and pupate. When they become adults, they bore out of the bark and fly away to infest another, nearby tree.

Historically, the southern pine beetle has been limited to the American Southeast, Mexico and Central America. Thanks to global warming, the beetle has journeyed north to the pitch pine forests of New Jersey in recent years and even to some areas of New England. Ayres says he’s stunned at how quickly climate change has warmed up cold areas, facilitating the beetles’ migration.

“Over the last 50 years the average temperature has changed by maybe 1 degree Fahrenheit,” says Ayres. “But the coldest night of the winter has warmed up by seven to eight degrees, a huge amount. Every few years it fluctuates, but the trend used to be that at least every few years it would get to about 0 degrees, cold enough to kill most southern pine beetles. Now that doesn’t happen nearly as much, so they’ve responded by increasing distribution limits and killing more trees.”

It’s not just warmer climates that have allowed pests to flourish in new places. Insects such as the emerald ash borer and hemlock woolly adelgid, for example, hitch a ride from Asia or Europe on live plants or wooden pallets used for shipping. The insects quickly fly away once they reach land, where they find a similar host tree. Though the phenomenon occurs all over the world, New England is a global hot spot for nonnative species. “Most forest insects have special requirements. They don’t just eat trees, they eat some specific tree—and we have it all,” Ayres explains. “So a random insect comes in and it’s more likely that somewhere within flying distance of the port of entry there’s going to be a host tree that it recognizes because it is similar enough to its host tree at home.” Experts point out that the multi-billion-dollar cost of dying trees caused by nonnative insects tends to fall on residential property owners and local governments that must cut down the newly killed trees before they fall and cause more damage.

Southern pine beetle outbreaks have been suppressed through a strategy of “cut and remove.” First, discrete local infestations of highly aggregated southern pine beetles are identified from aerial surveys. Then salvage loggers can cut out infested trees, plus a modest buffer. “This practice usually stops growth of the local infestation by removing beetles from the forest and disrupting the pheromone plumes that catalyze mass attacks on trees,” says Ayres. “When most such infestations in a forest are successfully suppressed, the regional beetle population is reduced to such low levels that it can no longer employ mass-attacks to kill trees, and then natural forces can maintain the beetles at non-epidemic levels for many years without further suppression.”

Such tactics have worked in the southeastern United States, where sawmills, paper mills and similar businesses have an incentive, but there is no such mechanism in places such as New Jersey. Experts have had some limited success by introducing predatory species, and tree breeding programs can help.

Ayres says the most effective solution will target nonnative species and come in the form of smart legislation. “We need national laws that will restrict the movement of wooden pallets into North American ports,” he says. “If we cut down or greatly reduced the import of live plant materials, there would also be an immediate effect. There are three headless horsemen of global change that are driving the way planet earth is changing: climate change, change in land use from growing human populations, and the movement all over the world of nonnative species. Reducing growing populations, stopping the cutting of forests for urban areas and reducing greenhouse emissions are hard challenges, but everyone should be in favor of this.”

Tiffanie Wen is a freelance writer who has written for the BBC, The Atlantic and The Daily Beast. She’s currently based in Lebanon, New Hampshire.