Bing! It’s the sound of a bat knocking a sweet stand-up double into left field. It’s what an actor hears when inspiration strikes and he gets a bead on his part. It’s the bell that signals the arrival of a brilliant, slightly insane idea, such as turning a minor league baseball franchise into a rambunctious assault on Major League thinking.

Bing: It’s the name of the man whose biography encompasses all this and more—Neil “Bing” Russell. Russell, who died in 2003, was an outsized force of nature in whose life the national pastime and Hollywood fame deeply and happily entwined. He acted in movies and owned a ball club. He hung out with Joe DiMaggio as a kid and John Wayne as an adult.

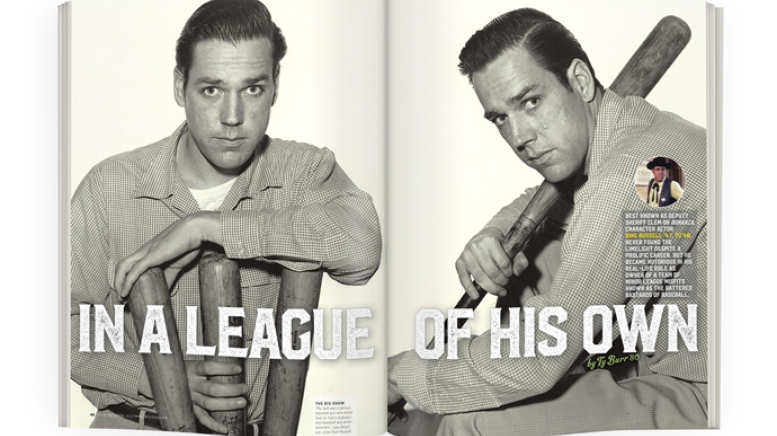

Why isn’t he better known? In part because Russell was a character actor, the guy you saw in dozens of film and TV shows but could rarely put a name to. In part, he has been eclipsed by his son, Kurt Russell, who went into the family business and became a much bigger star than his old man. It’s also true that a below-the-title legend such as Bing Russell, hardworking but not household-name famous, can be forgotten in the passage of time.

Except in Oregon, where in the mid-1970s he took an independent Class A ball team of misfits and burnouts and turned them into the Portland Mavericks, to the delight of fans and national sportswriters and the horror of Major League Baseball executives. In Oregon they’ll remember Bing Russell forever.

If you’re familiar with his face at all, it’s probably because you watched a lot of TV Westerns and crime dramas in the 1950s and 1960s. Russell had speaking roles in classic movies such as The Magnificent Seven (1960) and John Ford’s The Horse Soldiers (1959)—his character gets his leg amputated in that one—but his bread and butter was episodic TV, and Russell was everywhere. His most well-known recurring part was Deputy Sheriff Clem Foster on Bonanza, a role he played 57 times during the program’s run from 1961 to 1972. But finding a show from that era in which Russell didn’t appear at least once is virtually impossible. He was even on The Monkees.

“His numbers are ridiculous,” says son Kurt. “I think he did over 800 television shows and movies. He died 126 times. He died more times than I’ll ever work in my life. He worked, worked, worked, worked, worked. That’s how he put food on the table, put shoes on feet.”

That relentless ethic was honed at Dartmouth but learned from no less an Olympian fount of experience than the fabled “Murderers’ Row” of the mid-1930s New York Yankees. Growing up, Russell had the dream job of every American kid: He was the Yankees’ good-luck errand boy at spring training in Florida, in New York and on the road. He smuggled peanuts to future Hall of Famers Joe Gordon and Red Ruffing. An ailing Lou Gehrig took his last swing in baseball on April 13, 1939—the second of two home-run blasts in an exhibition game against the Dodgers—and handed the bat to Bing to keep. (The bat stood for years in an umbrella stand in the Russell home. In 2011 the family auctioned it off for more than $400,000.)

It was a perfect union of baseball smarts and outrageous showmanship—the role Russell had been angling to play his entire life.

The story of how Russell joined the Yankees is a flexible piece of family lore, one whose details change slightly depending on the teller, whether it’s Kurt or Bing’s widow, Louise, or his grandson, Chapman Way, who, with brother Maclain, made a 2014 documentary about Bing and the Portland Mavericks called The Battered Bastards of Baseball. (It’s available on Netflix and highly recommended.) Bing himself was a championship raconteur, and who knows how many versions he told?

But this is the way it goes, more or less: Bing’s dad, Warren “Bud” Russell, was a pioneer aviator who ran commercial seaplane airbases both in New England—Bing was born in Brattleboro, Vermont, in 1926—and in St. Petersburg, Florida, near the Yankees spring training camp. The team’s storied pitcher Lefty Gomez liked to fly, but Yankees manager Joe McCarthy didn’t want him to, so Gomez took to accompanying Russell Sr. on flying runs on the sly. That’s how he recognized 7-year-old Bing outside the spring training field, where the boy was battling an entire gang of kids who’d stolen a stray fly ball he’d caught.

“Stick with me, son, and you’ll have all the baseballs you want,” said Gomez—or something like that. What no one disputes is that Bing became the clubhouse kid from that point forward, and Gomez remained a mentor and close friend until the pitcher’s death at 90 in 1989. As did all the Yankees, young and old. “It was an interesting household,” Kurt recalls about growing up with Bing for a father. “Ballplayers, really big-name ballplayers, would be around. Lefty would bring in anybody—Willie Mays, Joe DiMaggio, you name it, they came to the house. These weren’t just baseball stars. They were gods.”

But we’re getting ahead of the story. Winter home base for the Russells was Rangeley, Maine, where Bing went to high school, played baseball and basketball, and got his dramatic feet wet in school plays. He graduated in 1943 into a country waging war in Europe and the Pacific. Luck was with him: The Navy V-12 College Training Program, offered at more than 130 colleges and designed to turn out officers, gave Russell a free ride at Dartmouth. He was one of a dozen selected from Maine for the program, and his first choices were MIT and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. But Daniel Webster’s alma mater turned out to be a good fit.

“Bing got a very lucky break there,” says his widow, who now resides in Thousand Oaks, California. “Not only did [V-12 students] take all the naval courses, they had to do the regular courses as well. It was a very strenuous thing.”

But Russell prospered. He lived in Hitchcock Hall and became a brother at Zeta Psi (years later, he would regularly drop into the fraternity during his family’s annual cross-country summer drives from Hollywood to Maine). Starting in 1944, his sophomore fall, he joined the Dartmouth Players under the directorship of Warner Bentley, where his first production was the medical melodrama Yellow Jack. Seventeen of the play’s 24 roles were played by V-12 trainees, a mark of how thoroughly WW II transformed Hanover.

“The most outstanding performance was given by Neil Russell, a newcomer to the Dartmouth Players,” said the Dartmouth Log. “His utmost sincerity and feeling for the character he played made the audience believe he really did care about yellowjack [fever] and its effect on man.” Russell also appeared in The Hasty Heart as a brash American officer. A surviving photo from the era shows the young Bing sporting a most fraudulent stage beard.

The brashness extended offstage. A story goes that Russell’s handwriting was so atrocious that during his freshman year a professor graded one of his papers poorly simply because he couldn’t read it. Whereupon Russell walked over to the home of President John Sloan Dickey ’29, invited himself in for dinner and successfully made a case that he could and should dictate his papers to a student with more traditional writing skills.

It’s unclear if Russell played baseball in Hanover. There are photos of him in a Dartmouth uniform, swinging a bat and making like a fielder, but his son says Bing played only one game. “He and the coach didn’t get along, I guess,” Kurt says with a laugh. “He hit a home run on a 3-0 pitch. The coach gave him the sign to take [the walk], and my dad hits it out of the park. And as he rounds third, the coach sticks his hand out to shake it, Yeah, atta boy, and my dad didn’t shake his hand—You told me to take it. And that was the end of that.”

Professional ball, though? That was another matter. Russell graduated cum laude with a degree in business administration and almost immediately set out to become a minor leaguer. The Yankees connection came in handy. Lefty Gomez was affiliated with the team’s Class D outfit, the Carrollton Hornets of the Georgia-Alabama League, and that’s where Russell found himself for a season and a half starting in 1948.

He hit a dismal .182. Even more ominously, he was beaned and knocked unconscious by a foul ball—twice. “That was kind of the joke in the family about why he was so erratic and eclectic and strange—he’d been hit in the head with a baseball,” says grandson Chapman.

By then Russell had a wife and a child on the way. He had met 16-year-old Louise Crone of Newport, New Hampshire, in 1944. Her mother had told her to never, ever talk to sailors but, according to Louise, “Bing said, ‘Look, you might as well talk to me, because I’m going to marry you.’ ” Two years later, he did. At his death they’d been together 57 years.

He went to Springfield College in Massachusetts for a degree in physical education, then returned to Maine to coach the Rangeley high school basketball team all the way to a state championship. And then? With two children by now (Kurt followed older sister Jill) and a stake of $1,500, Bing moved the Russell family out West to try acting. “It was scary, but nothing ventured, nothing gained,” says Louise.

He could ride a horse and do his own stunts—that counted for a lot in an entertainment industry still cranking out Westerns for the big and little screens. Sometimes Russell would act in three different shows in one week. At other times, nothing would come in. Russell rolled with it.

“My dad loved acting,” Kurt says. “He loved the process, he loved talking about it. He had lots of stuntman friends and they would be at the house. I remember all the Bonanza guys coming over: Michael Landon, Pernell Roberts, Dan Blocker.” When he had free time Bing involved his kids—daughters as well as sons—in professional youth auto racing. “I won a world series and five nationals and my sister, Jill, won six national championships,” says Kurt. “My sister, Jamie, had a world speed record. There were times that we didn’t necessarily have much furniture in the living room, but we had $3,000 Italian carburetors in our cars.”

Bing was a character—gregarious, obstreperous, quick to anger, quick to forgive. “He was always larger than life, very colorful,” remembers Chapman. “When I played Little League baseball he got thrown out of two or three of my games for yelling at the umpire. I remember as a kid just being mortified and humiliated, and now I look back and think it’s kind of hilarious.” Adds Kurt, simply, “He was a big personality and my mother was absolutely a saint.”

Bing’s third act was a great one, though. In 1972 Bonanza was canceled, and the steadiest of Russell’s acting gigs dried up. Worried that his father was sitting idle, Kurt prodded Bing to reawaken his baseball dreams. The Triple-A Portland Beavers had just called it quits after decades of lackluster local support, and Russell father and son decided to buy their way into the franchise—for a grand total of $500—and start a Single-A club.

And not just any Single-A club. From 1973 to 1977 the Portland Mavericks were the only independent minor league team in all of baseball, an anomaly in an era in which major league teams used the system to farm and develop talent for the Big Show. Once there had been hundreds of unaffiliated teams and leagues across America. Now there were none—until Bing announced he wanted to take baseball back to what he called “the straw hat and beer days.”

It was a perfect union of baseball smarts and outrageous showmanship—the role Russell had been angling to play his entire life. The fans in Portland, Oregon, and, increasingly, around the country, loved it. The MLB suits hated it. True to their name, the Mavericks flew a defiant freak flag, holding open tryouts for anyone who’d harbored a fantasy of playing pro ball. Prospects hitchhiked across the country for their shot at glory.

Russell hired as his manager Frank “The Flake” Peters, who’d played 16 seasons as a decent third baseman with the Baltimore Orioles organization. Pitcher Rob Nelson relocated from South Africa to Portland just to play for the Mavs. Jim “Swannie” Swanson, then the only left-handed catcher in baseball, signed on. Kurt played second base. Larry Colton, another pitcher, had only one major league game under his belt and was working as a high school English teacher.

But Russell had a deep knowledge of the game and an eye for players. Above all, he wanted to have fun. The team he assembled looked a mess—“They led the league in stubble,” says Nelson in the documentary—but they had the goods. In their first game pitcher Gene Lanthorn threw a no-hitter, and it got better from there. By the end of the Mavericks’ second season Bing had been named Class A Executive of the Year.

After NBC’s Joe Garagiola ran a two-part special on the team that year, the owner got a phone call from Jim Bouton, the 38-year-old pitcher still in the major-league doghouse from his 1970 tell-all book, Ball Four. He wanted in, too, and so what if the pay was $400 a month? “Our motive was simple,” Bouton recalls in the documentary. “Revenge.”

In the end, the suits had the last laugh—but Russell made them pay for it. Chagrined over the Mavericks’ booming popularity, MLB executives decided there was a market for a Triple-A club in Portland, after all. That meant Russell would have to be bought out. After the 1977 season they offered him $26,000. Russell wanted $206,000. An arbitration panel looked at his Oregon miracle and told the suits, in effect, give the man what he wants.

That’s a roughly 41,000-percent return on his and Kurt’s initial $500 investment. Don’t ever say Bing Russell didn’t learn anything about business at Tuck.

In the aftermath Bing toyed with bringing a major league team to Washington, D.C., or Las Vegas, and Kurt Russell says his dad was seriously approached by industry insiders about taking the job of commissioner of baseball. “Which he laughed at and said, ‘You’d better think about that—I might say yes,’ ” says Kurt. “It would have been raucous. Baseball would be a lot different today if he had been commissioner.”

Russell died of lung cancer in 2003, but in the wake of his grandsons’ 2014 documentary, interest in the Mavericks story has heated up. Todd Field, the Mavericks’ adolescent batboy who grew up to become an Oscar-nominated director (2001’s In the Bedroom), is working on a feature film script and hopes to get the project in front of the cameras within the next few years.

Leave it to the son to eulogize the father and the three interests he developed at Dartmouth then brought to fruition in the wider world. “My dad was a serious baseball guy who knew how to marry business and baseball and entertainment,” says Kurt. “That was his gift. And one of the reasons he made money was because he didn’t sell pantyhose at second base. He sold baseball to the people of the town. It’s a big difference. And he understood entertainment, that entertainment comes from good competition and winning.”

He also understood having a blast while you’re doing it. Looking out over the current state of the movies and professional baseball, it’s hard not to wonder if we’d all be better off with a little more Bing in our lives.

Ty Burr is the film critic for The Boston Globe.