Interviews With Young Alumni

Better Living Through Design

Your website bio states that you are “most keenly interested in self-sufficiency, appropriate technology, and domestic economy.” What do those ideas mean to you?

I’m a very practical person, and I take a lot of satisfaction in the idea of doing things for yourself. Every human has the ability to be self-reliant or, at least, the capacity to be a little more involved with their day-to-day existence. Being able to cook well and maintain goods instead of buying new ones—these are really attractive ideas for me.

When did you first become interested in timber framing?

During my sophomore year at Dartmouth a timber framer named Ira Friedrichs hosted a Cabin and Trail workshop. We built two outhouses for the Appalachian Trail—all wooden joints with no nails or screws. That was mind blowing. After that, I worked on a new Velvet Rocks Shelter to replace the original—built by Will Brown ’37—that had rotted away. We had the tennis team help carry all the timber onto the building site, and we got the roof on in the winter, right as the snow was starting to fall. After graduation I helped build the sugarhouse out at the Dartmouth Organic Farm. I felled the trees and we milled all the wood on site.

You’ve also designed a wide range of soft goods and tools for Archival Clothing and Best Made Company. How did you get started in clothing design?

In spring 2009 I was working on a crew at Mount Moosilauke and snail mailing with a friend back home in Eugene, Oregon, who had a blog that featured old clothing catalogs. She mentioned that she wanted a certain kind of bag—she wished she could shop from the past for it. I said, “I’ll see if I can just make you something while I’m up here.” Then I was cleaning out a storage shed on Moosilauke and there was a big chunk of ice in the back corner. We chipped away at it and found an old cotton canvas tarp frozen into the ice. I cut it up with my knife, found a needle and thread, and sewed up a bag. It was a terrible bag, but my friend thought it was cool.

Did that experience lead to the founding of Archival Clothing?

After moving back to Eugene I designed a couple more bags to sell on the blog. I didn’t know anything about sewing at the time, but I took a class at the craft center and tried to copy what worked in old bags while adding what we wanted to the new ones. One thing led to another, and we started Archival Clothing. We did two shoulder bags that sold well and a backpack that got a huge amount of press. The business really took off thanks to the heritage menswear blog scene.

How did you end up at Best Made Company?

I moved to New York to study industrial design at Pratt and continued to work for Archival, mostly doing product design and helping with sales for the big accounts. Best Made was the first company to wholesale the Archival backpack. I started doing freelance design work for them, helping with some soft good designs, and they offered me a full-time design direction gig.

What did you do as design director?

The creative director would share a group of product ideas with me. Then I would create a collection of physically-designed goods that, once approved, would go off to production. I got to spend a lot of time in the garment district and also see the production process in hard goods factories—it was a fantastic education. It was also pretty surprising to find myself in New York City and using computer software to design ax sheaths that were going to be made in the thousands. Some of those moments you look around and just think, Is this real?

What lessons did you take away from your time at Best Made?

One of the most exciting things was spending time in factories to see the actual constraints on the manufacturing process and then learning to tailor designs to suit that process. You can make a product as complicated as you want, and the factory is going to make it happen, but it’s going to be time-intensive, the sewers aren’t going to like it, management is going to resent you, and it’s going to be really expensive.

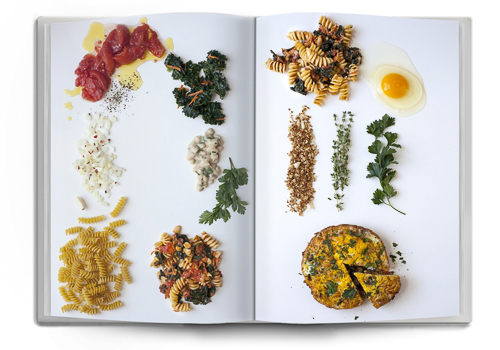

For part of your master’s thesis at Pratt you designed a cookbook without words. What was the concept behind that project?

The premise of the thesis was about self-reliance and self-education in the domestic kitchen. I was curious to see if placing constraints on the media inputs in a kitchen might encourage people to cook in a more intuitive way. Cookbooks tend to be very prescriptive—you follow the step-by-step directions and it becomes a performative routine. I wanted to provide an alternative that would be intentionally ambiguous and force you to improvise and fill in the blanks between missing pieces of information to create something new.

You’ve led a timber framing workshop during the past few summers. What inspired you to start teaching?

Three years ago a friend introduced me to Zach Klein—he helped start Vimeo, CollegeHumor, and the Cabin Porn Tumblr account. He had purchased a big patch of forest in Upstate New York called Beaver Brook and allowed a group of friends to help build things there. He asked me to teach a week-long workshop in timber framing. I’m not an expert by any stretch, but I knew enough of the basics of Japanese-style timber framing to teach a crew of six students how to build a really simple tree house. It was a blast, and this past summer we built a kitchen structure.

The short film Greenwood features you felling a tree at Beaver Brook and turning it into a stool. How did that project come about?

My friend Derek, who was another member of Beaver Brook, got me into carving spoons and at some point we decided to make a green wood stool. Green wood is not well-suited for industrial production, but it’s very willing to work with your tools and it’s so easy to carve and cut. It’s very satisfying, especially knowing that the vast majority of woodworking in human history has been done while the wood is green.

You recently started teaching design at University of Oregon. What advice are you passing on to your students?

I encourage my students to trust the process and to learn from doing. You can sit there and draw all you want, but at the end of the day, if you’re designing a backpack, you need to sew a bunch of backpacks. Even if you don’t quite know what you’re getting into yet, start doing stuff and something will happen. I’d rather see something that has a good idea behind it, even if it’s simple or basic, than something that’s really perfectly made but ill-conceived. The physical artifact is never quite finished, and that’s good, because it would be boring if everything just came back perfect.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. Header photo courtesy Adam Newport-Berra; all other photos courtesy Tom Bonamici.