There and Back Again

“You guys! You guys! You gotta come here and see this!” It was early December 1980, the end of my German language study abroad program (LSA), and I was one of 24 Dartmouth students on a train stopped at the border between East and West Germany on our way to West Berlin. East German officials had come and taken all our passports. We were waiting for them to verify that none of us was a threat.

It was dark, but we all pulled windows down to see what was going on outside. There on the dimly lit platform was an East German guard with a German shepherd. He was holding a flashlight and a mirror on a long handle and inspecting the underside of every train car. That was my introduction to the East German regime.

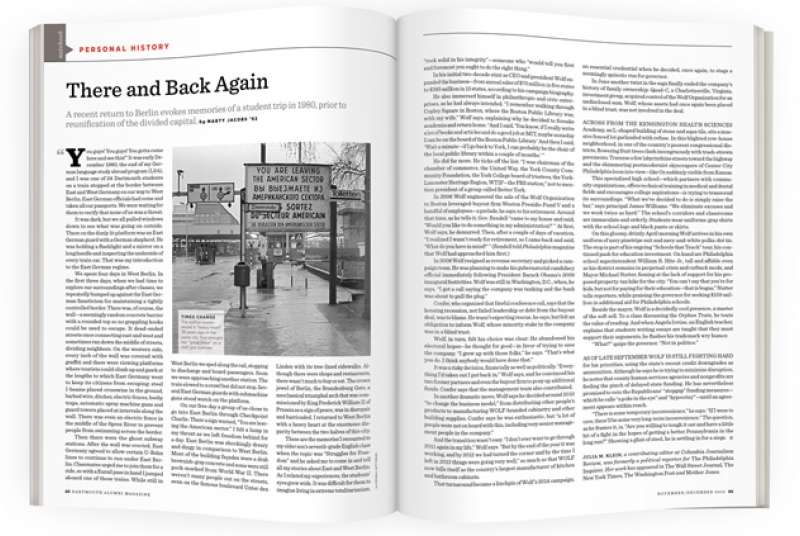

We spent four days in West Berlin. In the first three days, when we had time to explore our surroundings after classes, we repeatedly bumped up against the East German fanaticism for maintaining a tightly controlled border. There was, of course, the wall—a seemingly random concrete barrier with a rounded top so no grappling hooks could be used to escape. It dead-ended streets once connecting east and west and sometimes ran down the middle of streets, dividing neighbors. On the western side, every inch of the wall was covered with graffiti and there were viewing platforms where tourists could climb up and gawk at the lengths to which East Germany went to keep its citizens from escaping: steel I-beams placed crosswise in the ground, barbed wire, ditches, electric fences, booby traps, automatic spray machine guns and guard towers placed at intervals along the wall. There was even an electric fence in the middle of the Spree River to prevent people from swimming across the border.

Then there were the ghost subway stations. After the wall was erected, East Germany agreed to allow certain U-Bahn lines to continue to run under East Berlin. Classmates urged me to join them for a ride, so with a Eurail pass in hand I jumped aboard one of those trains. While still in West Berlin we sped along the rail, stopping to discharge and board passengers. Soon we were approaching another station. The train slowed to a crawl but did not stop. Several East German guards with submachine guns stood watch on the platform.

On our free day a group of us chose to go into East Berlin through Checkpoint Charlie. There a sign warned, “You are leaving the American sector.” I felt a lump in my throat as we left freedom behind for a day. East Berlin was shockingly dreary and dingy in comparison to West Berlin. Most of the building façades were a drab brownish-gray concrete and some were still pock-marked from World War II. There weren’t many people out on the streets, even on the famous boulevard Unter den Linden with its tree-lined sidewalks. Although there were shops and restaurants, there wasn’t much to buy or eat. The crown jewel of Berlin, the Brandenburg Gate, a neoclassical triumphal arch that was commissioned by King Frederick William II of Prussia as a sign of peace, was in disrepair and barricaded. I returned to West Berlin with a heavy heart at the enormous disparity between the two halves of this city.

These are the memories I recounted to my older son’s seventh-grade English class when the topic was “Struggles for Freedom” and he asked me to come in and tell all my stories about East and West Berlin. As I related my experiences, the students’ eyes grew wide. It was difficult for them to imagine living in extreme totalitarianism. As I left the school, it dawned on me that my LSA experience had instilled in me a fierce sense of civic responsibility. I would never give up my U.S. passport, and I vote in every election.

My work has also been influenced by my LSA. As a consultant, I am often bringing people together to create visions for the future or come up with solutions to major social issues. Although the insanity of what I witnessed in East and West Berlin propelled me toward a career in creating connections and strengthening relationships, I never thought reunification would happen in my lifetime, and I cried in 1989 when I saw the videos of ordinary people breaking down the wall with whatever tools they could find.

This past summer I finally had the chance to visit a reunited Germany and a reunited Berlin. As I was conducting a systemic inquiry for the Ph.D. program in which I am enrolled and was learning about how systems thinking can help us respond to the changes humans are introducing to Earth, I managed to take several afternoons to visit many of the places I remembered from 36 years ago. As I walked through Potsdamer Platz I crossed the two-brick line marking the location of the wall. The transformation since reunification was astounding. Tall, gleaming buildings towered overhead. Traffic coursed through the reconnected streets.

A short walk from the platz was the Brandenburg Gate, off limits to me in 1980. Beyond it I walked down Unter den Linden, now a bustling commercial district. The brownish-gray façades of the buildings I recalled had been replaced with more interesting colors and features. Finally, I reached Checkpoint Charlie. It was almost unrecognizable. The warning sign still stood, but it was now possible to have pictures taken with U.S. servicemen.

The changes in Berlin were breathtaking. My understanding of systems thinking and systems sciences was elevated to a new level that enabled me to make connections between what I was learning and what I was seeing. What Germany has accomplished gives me great hope that we, as part of a global society, can create positive transformational change when we put our minds to it.

Marty Jacobs is a consultant and Ph.D. student at Saybrook University. She lives in East Thetford, Vermont.