Some call them the “Dartmouth Mafia,” those friends and classmates who rallied around Reich after a diving accident in 1962 paralyzed him from the neck down. More than 50 years later, a decade after his death in 2005, a number of his Dartmouth friends are still there for him.

One of the earliest to visit Reich in the hospital, just 10 days after his accident, was classmate Jack Boyle ’52, who looked down at his pal, who played halfback on the football field, starred as an All-American in track and was a founder and coach of the rugby team, and commiserated about bad luck.

“Come on, Jack,” Reich shot back. “Walking’s not everything in life.”

Walking’s not everything in life.

Several evenings a week, while Reich recovered at Rusk Institute in New York City, John Rosenwald ’52 stopped by on the way home from work to help feed him. Perhaps the premier fundraiser in the city, “Rosie” spent most of his career as an investment banker at Bear Stearns and J.P. Morgan, and has given—and strong-armed others into giving—large contributions to Reich’s National Organization on Disability (NOD).

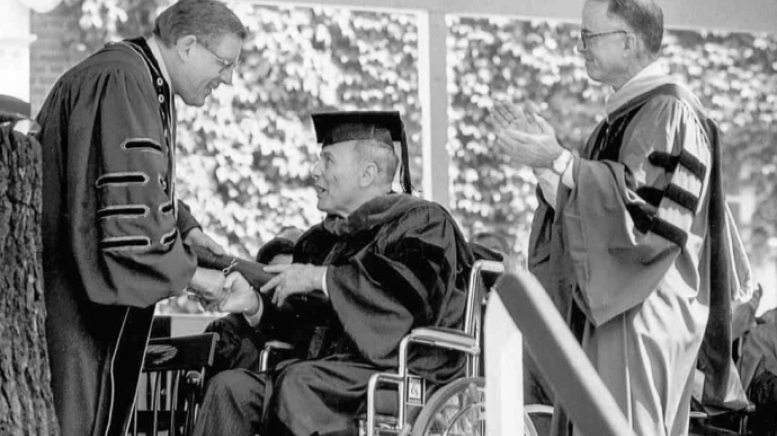

Forty years later, as chairman of the Dartmouth trustees, Rosenwald felt honored to wheel Reich from the podium to receive an honorary doctor of laws degree at the 1992 Commencement. Rosenwald remains active on the NOD board and executive committee.

At the time of Reich’s accident few people had ever seen anyone in a wheelchair. The disabled generally stayed home. They were invisible. President Franklin Roosevelt hid his wheelchair from public view, with the complicity of an accommodating press. He deliberately exposed his disability only when visiting a veterans hospital or a black college, to make a point about overcoming barriers.

Reich had been working at Polaroid when he had his accident. The day after, Polaroid’s legendary founder Dr. Edward Land told him, “As long as I’m at Polaroid, you have a job.” That meant the world to Reich. His wife, Gay, drove him to work each day until he learned to operate a car specially equipped with hand controls.

When Reich returned to work, he was met with polite reserve—colleagues wanted to be supportive but “they didn’t have the vaguest idea of what I could do and what I couldn’t do,” Reich recalled. “They hadn’t ever seen anyone come up the freight elevator in a wheelchair to the production floor.”

Another classmate at Polaroid, George Hibben ’52, had been senior class secretary when Reich was class president and manager of the football team when Reich played. Both belonged to Palaeopitus and Casque & Gauntlet and both had earned M.B.A.s at Harvard. “George organized everything for him, including his visits,” says Gay. “He was incredible.”

From early on Reich felt confident he would walk again. But when his recovery stretched out, he developed an interest in doing something about it—and perhaps helping others. He liked to quote Robert Frost, class of 1896: “You can be a king if it’s in you and in the situation.”

Granted a leave of absence from Polaroid to open up a new field of research on regenerating the central nervous system, he set up the National Paraplegia Association on a pingpong table in his basement—and persuaded distinguished scientists to write President Richard Nixon for support. That led to his becoming deputy secretary of state, where he worked with other countries to promote an understanding of paraplegia.

When the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed 1981 the International Year of the Disabled Persons, Reich became the first to address the body from a wheelchair.

Awareness of disability issues in the United States was slow in getting off the mark, so Reich left government to start a private-sector council, enlisting a high-powered team of chief executives. The U.S. program was built on partnerships between government and the private sector. When everything came together, the United States celebrated the International Year of Disabled Persons with 400 national organizations and 2,200 local community partnerships.

The international year was so successful that everyone wanted to keep it going. The UN proclaimed a Decade of Disabled Persons in 1982, and the organizers eventually formed NOD, with Reich as its founder and president.

It is a truism that many who get involved in the disability community have a friend or family member with a disability. Beyond the enormous responsibility of helping care for her husband (and four young children), Gay served on the NOD board and later served as interim president during a management transition. The night before Reich received his honorary degree Rosenwald surprised Gay with a crystal bowl honoring her contributions to what her husband had accomplished. Gay burst into tears. (She is still on the NOD board, and son Jeff is a director and cochairman of the finance committee.)

Many Dartmouth ’52s and several ’53s kept the organization going in the early days and through difficult times. It was hard to say no to Reich.

Few were closer to Reich than classmate, fraternity roommate and football teammate Charles “Doc” Dey ’52. Like Reich, Dey is one of those who make others stand a little taller. After graduating with an A.B. in history (with distinction) and varsity letters in football and tennis—followed by service in the U.S. Navy, a teaching stint at Andover and a tour with the Peace Corps—Dey returned to Dartmouth as associate dean. With President John Sloan Dickey ’29 Dey launched A Better Chance—an experiment to give minority students opportunities to prepare for college.

When Dey retired as the first head of the combined Choate School and Rosemary Hall, Reich challenged him to “do in the 1990s for people with disabilities what you did for minorities in the 1960s” and help them get into the workplace. So Dey launched NOD’s Start on Success, a public-private partnership to provide paid internships for inner-city public high school students with disabilities, those who are “triply disadvantaged,” he says.

Doc continues on the NOD board as vice chairman and member of the executive committee. For his lifetime dedication to education, racial equality and public service he was awarded the Tucker Foundation’s first Lester B. Granger ’18 Award for public service in 2002.

The list of supporters goes on. As an English major, Dick Watt ’52 always dreamed of writing a book. He wrote three—in addition to running his family’s specialty chemicals business—well-reviewed books on a little-known French Army mutiny in World War II (Dare Call it Treason), the tragedy of Germany and Versailles (The Kings Depart) and Poland between the wars (Bitter Glory). NOD enlisted Watt to produce a quarterly newsletter about the organization’s efforts to assist American soldiers with disabilities transition into meaningful civilian careers. His letters produced more than $600,000 from more than 200 Dartmouth friends—and created a cadre of NOD supporters, some of whom continue to give to the organization today. Watt signed off his letters: “Alan’s Dartmouth classmate and longtime friend.” In his obituary, Watt’s family suggested donations to NOD in his name.

Chuck Queenan ’52, a partner in a major Pittsburgh law firm, served on the NOD board for years—and continues as a generous contributor.

George von Peterffy ’52 was in the U.S. State Department with Reich. They were close, and George supported NOD.

Harry Goldsmith ’52 stayed in touch with Reich for medical interests. A clinical professor of neurological surgery at the University of California, Davis, they shared an interest in spinal cord regeneration.

Phil Beekman ’53, former CEO of Colgate-Palmolive, and Fred Whittemore ’53, a partner at Morgan Stanley, were early supporters—and served on the NOD board for years.

Jack Patten ’53, publisher of Businessweek, provided important space pro bono for NOD advertisements that helped build the organization’s CEO council.

NOD’s focus came from Harris polls that identified “pervasive gaps” between those with and without disabilities. The largest gap, which has changed little through the years, is in jobs. Harris president Humphrey Taylor believes that without Reich the ADA would not have become law in its final form. Former U.S. attorney general Dick Thornburgh agrees: “Alan was constantly making the case for it, bending every ear he could on the Hill and with opinion leaders.” The ADA was signed into law by NOD’s honorary chairman, President George H.W. Bush.

Reich also campaigned for the statue of Roosevelt in a wheelchair, which was not part of the original plan for his memorial in Washington, D.C. Reich lobbied Congress and raised the money. The statue of Roosevelt in his wheelchair is the only such monument of a world leader with a disability.

Reich and his wife believed that his accident happened for a reason. It gave him a purpose in life. He always wanted to contribute and he believed that his contribution was awakening international consciousness of disability. “When I was in school I had never seen anyone in a wheelchair,” Reich told me when I interviewed him for a possible book on disability. “There have been great, positive changes in attitudes toward participation by the disabled. I consider myself fortunate to be able to do the work that I do.”

In his 25th reunion yearbook Reich reported what he had been doing since graduation: marriage, Oxford, Army service, business school, Polaroid, children, U.S. Department of State, his accident.

“Three weeks after graduation I met Gay aboard a student ship to Europe. With some exceptions, life has been smooth sailing ever since,” he wrote.

His Dartmouth friends and classmates were privileged to have been along on this trip.

Ken Roman is a former advertising executive, author and longtime member of the NOD board. For more information on the passage of the ADA, click here: http://dredf.org/news/publications/the-history-of-the-ada/

Photo: Reich receives his honorary degree in 1992 from President James Freedman, left, as chairman of the trustees John Rosenwald ’52 joins the applause.

Related: Profile of Reich in the Mar/Apr 2005 issue of DAM.